Yesterday: The Dat So La Lee Basket Mystery

Fall 2022

Four baskets woven by legendary Washoe weaver Dat So La Lee were stolen from the Nevada Historical Society in 1978. The tale of their return reads like a Hollywood plot.

BY MARIA DAVIS DENZLER

This story originally appeared in the December 2002 issue of Nevada Magazine.

On a cold, blustery day in December 1978 a thief walked into the Nevada Historical Society’s museum gallery in Reno, lifted four prized baskets from their Lucite cases, and disappeared.

The baskets, created by the famed Washoe weaver Dat So La Lee and today worth $2 million, have found their way home and once again are displayed in the society’s permanent exhibition gallery. The story of their return reads like a tangled Hollywood plot involving shadowy criminals, mysterious telephone calls, Native American-art experts, and the FBI.

“When the new gallery was built two years ago, we added substantial security,” says Peter Bandurraga, the society’s director. “We spent over $300,000 alone constructing the new permanent exhibition, and it is well-protected. I don’t want anyone to get the idea that it is like something out of the movie The Thomas Crown Affair [with noisy alarms and slamming gates], but I will tell you that anyone who tries to get too close to the exhibits will be cut in half by a laser beam.”

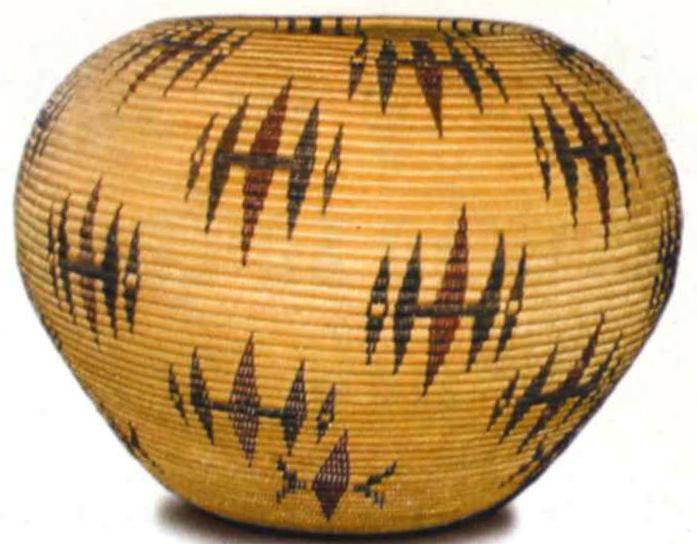

Bandurraga has good reason to be security conscious. Five low-lit display cases hold a group of 10 stunning baskets. The woven-willow creations of Dat So La Lee are known as degikup, a Washoe word referring to the incurving shapes of their tops. The stitched willow bodies, now soft brown with age, serve as a backdrop for intricate black and red geometric designs that appear to change size with the baskets’ contours.

In the low light, position on glass shelves, the baskets seem to float in air. Bandurraga points to each of the four recovered works of art—“Our People Used Magic Arrows,” “Bright Morning Lights,” “The Chief’s Compact,” and “Going to War”—in the historical society’s Dat So La Lee display.

“The names really have no meaning,” he said. “These are not ceremonial pieces. They are commissioned works of art.” He explains that according to the Washoe basketry expert Dr. Marvin Cohadas, Amy Cohn, the wife of Dat So La Lee’s white benefactor, Abe Cohn, made up names that had nothing to do with the Washoe Culture. She also fabricated stories and created a whole mythology around the baskets to promote their sale to white collectors in the early 1900s.

“Dat So La Lee and her work are the stuff of legends,” says Jim Haas, director of Native American, Pre-Columbian, and Tribal Arts at Butterfields Auction House in San Francisco. “Because of the superb quality of her work, its scarcity, and the mythology surrounding it, her art has become the symbol of American Indian basketry.” Haas estimates that Dat So La Lee’s finest degikup are worth approximately a half million dollars each. What is it about Dat So La Lee’s work that sets it apart from other Indian basketry and makes it so valuable? “Innovation,” says Cohadas, who is a professor of art history at the University of British Columbia. “Dat So La Lee, borrowing from neighboring tribes such as the Pomo and Maidu, invented the shape of her baskets and also invented many of her own design motifs. She was the first Washoe weaver to use the color red [redbud] in her coiled baskets, later combining it with the color black [bracken fern], traditionally used in Washoe coiled basketry, and also the first to use a very fine stitching technique. Her work is absolutely breathtaking.”

When Dat So La Lee died in 1925, most of her significant baskets remained unsold. In 1945, Abe Cohn’s second wife and widow, Margaret, sold 20 of Dat So La Lee’s major works to the state of Nevada for $1,500, or $75 each. (Their value today is well over 6,000 times that amount.) The state then gave 10 of the baskets to the Nevada State Museum in Carson City and the other 10 to the Nevada Historical Society in Reno.

The Nevada Historical Society’s baskets sat undisturbed for 33 years until the theft. No one knows exactly what happened.

“We had just finished a renovation of the gallery, and some of the cases had not been permanently secured yet,” says Phillip I. Earl, curator of history at the time. “I remember that it was a particularly slow day—not many visitors.”

One theory is that the thief or thieves walked into the building at noon, when most employees were at lunch. (In 1978, admission was not charged, and there was no internal security.) Once in the gallery, strong hands lifted the heavy, unsecured Lucite cases that housed the society’s basket collection and removed four degikup baskets as well as a smaller basket, made by an unknown weaver, that held several arrowheads. The thief then smuggled the loot out of the building in broad daylight.

“I opened the next morning and couldn’t believe they were missing,” recalls Earl, who discovered the theft and immediately called the campus police. An investigation revealed no leads. The baskets had disappeared.

Two years later, the historical society received an intriguing telephone call. A Santa Cruz attorney, representing an anonymous client who claimed to have two of the stolen Dat So La Lee baskets in his possession, called, asking for a finder’s fee of $2,500 for each basket. Society representatives, armed with insurance cash, viewed the two baskets in the attorney’s office and identified one of them, “Going to War,” as a missing Dat So La Lee degikup. They paid the $2,500 and returned to Reno, leaving the other basket behind. Bandurraga, who joined the historical society a year later, suspected from drawings made at the time that the other basket was also one of the stolen artworks. He scramble to recontact the attorney, but by then the mysterious client had disappeared.

“He said something about his client calling him from a telephone booth and using first names only, and he had no idea who the person was,” Bandurraga says.

It would be 17 years later before the other baskets resurfaced.

In 1997, a Tucson antiquities dealer named Paul Shepard purchased three undocumented willow baskets for $45,000. Seeking a buyer, he sent photographs of the baskets to an art appraiser in Palm Springs, California, for authentication. The appraiser, in turn, sent the photos to Marvin Cohodas, who routinely receives photos from art dealers seeking identification.

“When I saw the prints, my first thought was, ‘Thank goodness they’ve been found!’” says Cohodas. He notified the authorities, and the FBI joined the case.

After an investigation, Shepard was deemed in innocent party. He sued the State of Nevada, claiming ownership of the baskets, and in 1998 the Nevada Attorney General’s Office settled the case for $55,000. The FBI retained legal possession of the baskets pending further investigation.

Like small, silent witnesses, the three Dat So La Lee degikup sat in a secure metal cabinet at the Nevada Historical Society—to which the FBI held the only set of keys—for more than a year until the FBI officially returned the baskets to the society.

“I was privileged to be involved in their recovery,” says Cohodas, a renowned basket weaver himself. “I have incredible admiration for Dat So La Lee’s work, and I’m thrilled that these wonderful pieces are back in the museum where the publica can enjoy their beauty.”

Bandurraga says that Cohodas is the real hero of the story. “He did the right thing, and that is why the baskets are on display in the museum today.”

The identity of the basket thief remains a mystery, and the smaller basket and the arrowheads were never found. Experts who examined the recovered degikup baskets for clues found faded areas that indicated the baskets may have sat on a table in a room in some direct sunlight for many years. A small wear pattern was discovered on the inner rim of each basket, suggesting that someone periodically may have picked up the pieces with just one finger to dust them or admire their beauty.

“We’ll probably never know what really happened to the baskets or where they have been for all these years,” says Bandurraga. But that is not something he thinks about. “We’re not going to lose them again. They’re back home now, and they’re here to stay.”