The Last Roadhouse

January – February 2016

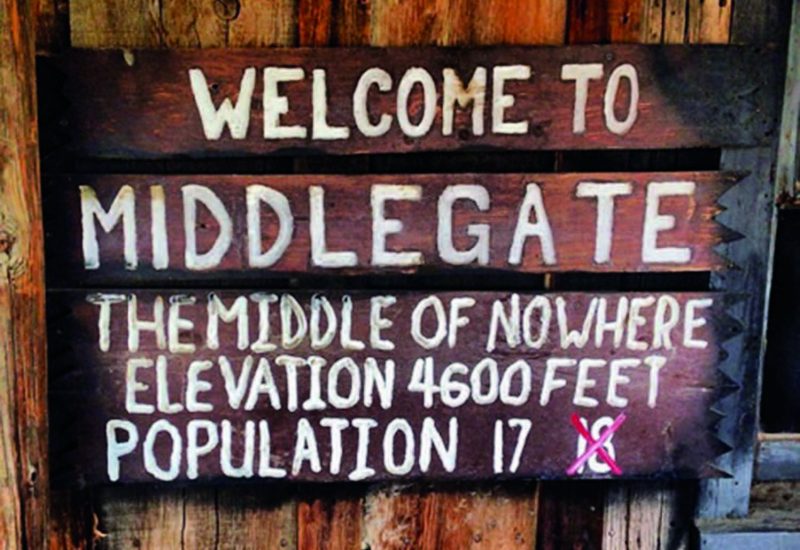

Middlegate Station balances on the edge of history and extinction.

BY LISETTE CHERESSON

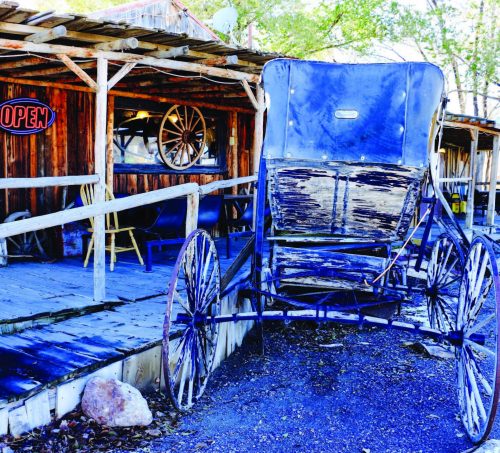

Driving along Highway 50, even seasoned road-trippers may find themselves a bit of panic. Once they’ve ridden the ghost train in Ely or visited the Eureka Opera House, there’s a kind of nothing that conjures visions of lone cowboys on horseback; the kind of nothing country songs beg into psyche. Mountains rise and fall against stark desert landscape. The power lines end. And then a patch of green emerges in the distance, and an old wooden structure reveals itself: Middlegate Station, the only settled area between Austin and Fallon.

Driving along Highway 50, even seasoned road-trippers may find themselves a bit of panic. Once they’ve ridden the ghost train in Ely or visited the Eureka Opera House, there’s a kind of nothing that conjures visions of lone cowboys on horseback; the kind of nothing country songs beg into psyche. Mountains rise and fall against stark desert landscape. The power lines end. And then a patch of green emerges in the distance, and an old wooden structure reveals itself: Middlegate Station, the only settled area between Austin and Fallon.

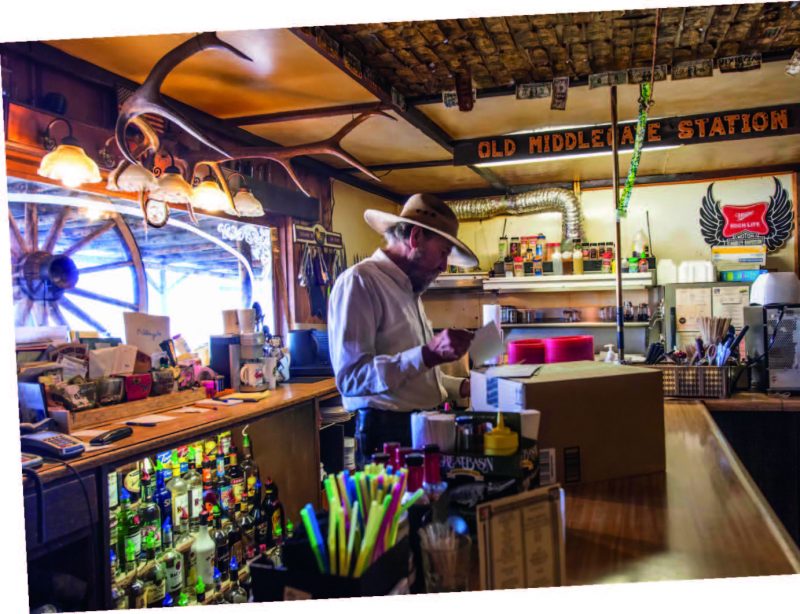

“People often ask me, ‘How can you live out here like this?’ ” says Fredda Stevenson, who bought Middlegate in 1984. Fredda currently operates the bar/motel/restaurant complex with her husband, Russ.

“I can’t imagine living anyplace else. Any freedom that we have left, I have out here,” she says. “I think when people come out here they feel at home. And that’s a good feeling.”

A PLACE FOR EVERYONE

One reason people feel at home in this middle of nowhere is shared heritage. Middlegate is one of the last Overland Stagecoach roadhouses still in operation. Russ and Fredda restored the existing structure to its original glory by reclaiming wood from nearby abandoned mining shafts, and the result is a living museum that embodies the last vestiges of an American way of life.

One reason people feel at home in this middle of nowhere is shared heritage. Middlegate is one of the last Overland Stagecoach roadhouses still in operation. Russ and Fredda restored the existing structure to its original glory by reclaiming wood from nearby abandoned mining shafts, and the result is a living museum that embodies the last vestiges of an American way of life.

Fredda calls her decorative tchotchke her treasures—there’s a serious collection of Western nostalgia adorning the walls of Middlegate, including 19th-century newspapers found on site. There’s a “hero wall,” boasting U.S. Armed Forces patches (mostly gifts from local military members), and the bar ceiling is covered in dollar bills signed by patrons and passerby. One of the prized bills is Asian currency gifted to Middlegate by tourists, Russ says, “who came all the way from Mongolia just to see the last of the Old West.”

Marvin Smith is a nomadic rancher who occasionally works grazing cattle on land surrounding Middlegate.

“It is traditional out here,” Marvin says. “It’s kind of like the Old West never died.”

Towns like Middlegate are essential, he believes, because if you’re hurt out on the range there’s some- where to go. But their necessity is as emotional as it is practical. Towns like Middlegate provide Marvin— and people like him—with a community they would otherwise lack. Rodney Leach is a truck driver based in the small town of Pahrump, about 300 miles south of Middle- gate.

Towns like Middlegate are essential, he believes, because if you’re hurt out on the range there’s some- where to go. But their necessity is as emotional as it is practical. Towns like Middlegate provide Marvin— and people like him—with a community they would otherwise lack. Rodney Leach is a truck driver based in the small town of Pahrump, about 300 miles south of Middle- gate.

“There’s not a person that works here who doesn’t make you feel like you belong,” Rodney says.

In this way, Fredda and Russ perpetuate the historical social fabric of a roadhouse as well as the physical. They’re known for taking in the destitute and helping them back on their feet and back on the road—in the way that roadhouses used to be stopovers for travelers who would occasionally need a favor.

“They save people from the worst all the time,” says Paul Smith, the motel housekeeper and resident musician. “They got me set up, helped me with my career,” he says, explaining that everyone who works at Middlegate works for tips, room, and board.

“Because of them, we’ve all learned teamwork under tough conditions. This is gas, food, lodging— off-the-grid rustic,” Paul says proudly, “but we love it.”

GEOGRAPHY OF HOPE

It’s the “off-grid” bit that makes the current situation in Middlegate challenging—and what is driving their current economic crisis.

It’s the “off-grid” bit that makes the current situation in Middlegate challenging—and what is driving their current economic crisis.

“When I bought this place,” Fredda says, “diesel was 30 cents a gallon.”

They run the entire town on a single generator—a finicky machine on good days. Because of the high cost of fuel, they’ve been operating in the red for years. The Stevensons have applied for 27 grants to date, but have been rejected for all. In the 1990s, they called on NV Energy (then Nevada Power Company) to put in a grid in their area, which ultimately did not happen. Most grants for rural development are awarded to communities or institutions that are on-grid, because the saved energy cost can then be put back into the system.

Sarah Adler, the director of Nevada USDA Rural Development, says that while the agency does its best to meet the needs of rural residents, there’s only so much federal and state tax money to allocate. Sarah and her office worked with Middlegate to get them into the Rural Energy for America Program (REAP)—a subsidy that could offset 25 percent of an energy-efficiency installation like solar. Unfortunately, even if they had been accepted into the REAP, their costs would still have been astronomical.

For Middlegate to be approved for a low-income USDA loan, there has to be a solid revenue stream to repay it. Fredda knows that her operating costs are enough to scare any lender.

“That’s really the challenge we’re facing with Middlegate—it’s a dream,” Sarah says. “It’s history and it’s precious, but for some of the forms of assistance that are available, there needs to be an economy that’s predictable in order to meet the need.”

Middlegate’s challenges aren’t unique, according to Professor Paul Starrs, chair of the history department at University of Nevada, Reno. They’re the same problems of access that affect many Americans living in rural locales.

“But just as the person in charge of rural development concerns themselves with rural internet access, it’s probably time to start think- ing about how these truly rural communities can become autonomous in terms of power,” he says.

“But just as the person in charge of rural development concerns themselves with rural internet access, it’s probably time to start think- ing about how these truly rural communities can become autonomous in terms of power,” he says.

For now, Fredda and Russ are relying on their regulars to provide them with the flow of customers they need to stay afloat. They don’t know, however, how long they’ll be able to keep it up. Paul Starrs refers to Middlegate as the embodiment of what Wallace Stegner called the “Geography of Hope.” Middlegate, as it exists today, provides necessary services and community for people who are carrying on a way of life that matters. It embodies the spirit of radical self-reliance and rugged individualism. Its loss is something that would affect us all.

“It’s a great part of history.” the professor says. “And people like Fredda represent a force of human nature…and that’s a very good thing.”

For more information on Middlegate Station and its current challenges, don’t miss the upcoming documentary, “The Last Roadhouse.” Visit lastroadhouse.com for more information.