Yesterday: The Big Bang Theory

January-February 2018

From the Dunes to the Mapes, Nevada hotels have discovered a dynamite method of urban renewal.

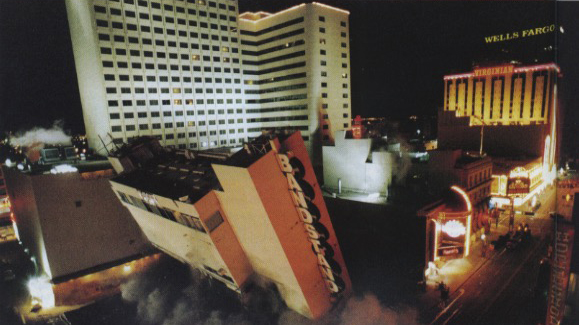

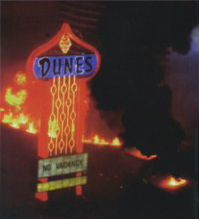

In Nevada, demolishing old hotels to replace with something bigger and better has become a common practice. In Las Vegas, the trend started in 1994 with the implosion of the Dunes Hotel, which had been built in 1955. The Dunes was replaced by the 3,000–room Bellagio, which at $1.8 billion is the most expensive hotel-casinoever built.

In 1995, the Landmark, erected in 1969, was the next outdated Las Vegas hotel dynamited. Its destruction was followed a year later by the implosions of the Sands—playground of the Rat Pack in the early 1960s—and the Hacienda, a Strip fixture since 1956. The site of the Landmark became parking for the Las Vegas Convention Center. The Sands lot was turned into the Venetian, and the Hacienda was transformed into Mandalay Bay. More recently the Aladdin, which opened in 1966, was blown up to make way for a new Aladdin. Meanwhile, in Reno, three casinos dating back to the 1930s and 1940s have been demolished. Harolds Club and the Nevada Club were imploded as part of Harrah’s future plans, while the Mapes Hotel was leveled on Super Bowl Sunday.

In 1995, the Landmark, erected in 1969, was the next outdated Las Vegas hotel dynamited. Its destruction was followed a year later by the implosions of the Sands—playground of the Rat Pack in the early 1960s—and the Hacienda, a Strip fixture since 1956. The site of the Landmark became parking for the Las Vegas Convention Center. The Sands lot was turned into the Venetian, and the Hacienda was transformed into Mandalay Bay. More recently the Aladdin, which opened in 1966, was blown up to make way for a new Aladdin. Meanwhile, in Reno, three casinos dating back to the 1930s and 1940s have been demolished. Harolds Club and the Nevada Club were imploded as part of Harrah’s future plans, while the Mapes Hotel was leveled on Super Bowl Sunday.

…AND THE LONG GOODBYE

BY RICH MORENO

This story originally appeared in the May/June 2000 issue of Nevada Magazine.

Its guests included Marilyn Monroe, Walter Cronkite, cowboys on a spree, but the Mapes ended with an unglamorous bang.

Time ran out for the Mapes Hotel on Jan. 30, 2000. That morning I turned on my television and, at 8:03 a.m, watched the 12-story Reno landmark shiver briefly and then collapse in an ugly heap of metal, brick, and concrete. Earlier, I had considered driving down to watch the spectacle, which attracted thousands of onlookers, but I decided I didn’t want to be a part of the Mapes’ public demise.

Time ran out for the Mapes Hotel on Jan. 30, 2000. That morning I turned on my television and, at 8:03 a.m, watched the 12-story Reno landmark shiver briefly and then collapse in an ugly heap of metal, brick, and concrete. Earlier, I had considered driving down to watch the spectacle, which attracted thousands of onlookers, but I decided I didn’t want to be a part of the Mapes’ public demise.

I’m not sure why I liked the Mapes. I’d never worked in the hotel and, before it closed, had been inside only a couple of times. But after two decades of living in northern Nevada, it was familiar to me.

Whenever I was in downtown Reno, I expected to see the Mapes standing tall alongside the Truckee River, as it had for more than half a century. So when the historic hotel crumbled in a giant cloud of dust on Super Bowl Sunday, I felt sad, as if someone I knew had passed away.

In recent years, blowing up venerable hotel-casinos has become a Nevada spectator sport. Since 1994, the Dunes, Landmark, Sands, and Hacienda in Las Vegas and Harolds Club, the Nevada Club, and the Mapes in Reno have been imploded out of existence.

In the case of the Mapes, its destruction came despite intense lobbying by Reno preservation groups and the National Trust for Historic Preservation, which had listed the Mapes as one of the nation’s most endangered historic sites. The hotel had sat empty on the corner of First and Virginia streets since 1982, when it closed for financial reasons. Reno officials decided to have the structure demolished so it could be replaced by something newer.

But while the building may be gone, plenty of memories remain. The Mapes was Reno’s grandest hotel when it opened on Dec. 17, 1947. At 123 feet high, it was the tallest building in Nevada and the first high-rise in the country that was designed to house a hotel, restaurant, and casino under one roof.

The Mapes had 250 hotel rooms as well as 40 large guest apartments on the building’s comers. The 12th floor of the hotel was reserved for the Sky Room, a 12,000-squarefoot dining-and-dancing area with a panoramic view of Reno. Over the decades, the Sky Room hosted a glittering assortment of entertainers such as Sammy Davis Jr., Liberace, Rudy Vallee, and Tony Bennett.

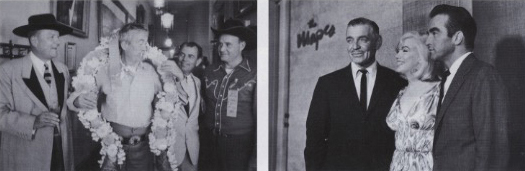

From the late 1940s to the late 1960s, the Mapes was Reno’s showcase hotel. In 1959, the cast of “Bonanza” stayed at the Mapes during the world premiere of the television show at Reno’s Granada Theater. A year later, many members of “The Misfits” cast, including stars Marilyn Monroe and Montgomery Clift, lived for several months at the Mapes while the movie was filmed in the area.

“Misfits” director John Huston (wearing wreath)with Lucius Beebe of the Territorial Enterprise (left) and Charles Mapes (far right). Clark Gable, Marilyn Monroe, and Montgomery Clift meet the public at the Mapes in 1960.

In fact, Harry Spencer, who served as publicist for the Mapes from 1951 to 1971, recalled in a “Reno Gazette-Journal” interview that he literally hijacked two movie studio representatives making arrangements for the film. Apparently, the advance team had decided the cast would stay at the rival Holiday Hotel when Spencer and his boss, Mapes general manager Walter Ramage, met them at the bar at the Holiday. After offering them a better deal to switch to the Mapes, Spencer and Ramage quietly and quickly hustled the two advance men out of the Holiday—they even carried their luggage—and checked them into the Mapes. “It proved to be the most lucrative piece of business the Mapes ever got,” Spencer said.

Nineteen-sixty might be considered the high point in the Mapes’ existence. In addition to serving as the headquarters for The Misfits crew, the Mapes was one of the host hotels for the Winter Olympics at Squaw Valley. A room on the hotel’s top floor was converted into the Winter Olympics Press Club and filled with wire service teletype machines, telephones, and typewriters. National media figures, including Walter Cronkite of CBS and Jim Murray of the “Los Angeles Times,” wandered into the room to file stories and then bellied up to the hotel bar for refreshments.

By the early 1970s, however, the Mapes had begun to fade. The change was gradual. Just as Las Vegas eclipsed Reno as the gaming center of Nevada, the Mapes lost its luster as Nevada’s premier hotel-casino. During the 1970s, the hotel largely remained the same while Reno grew and the nature of the state’s gaming industry changed. Nevada’s hotel-casino owners began to realize that it was no longer enough to have a casino, restaurant, and rooms under one roof. To compete with new gaming destinations like Atlantic City, hotel-casinos had to be bigger and offer more amenities.

Compounding the Mapes’ problems was the fact that in 1969 owner Charles Mapes had opened the Money Tree Casino, which eventually became a money pit. In 1980, Charles Mapes was forced to close the Money Tree and file for protection under federal bankruptcy laws.

By the early 1980s, the Mapes was an aging property in serious need of new investment. Many of the rooms had their original furnishings and fixtures, and the hotel lacked a sprinkler system, required for all high-rises after the MGM Grand fire in Las Vegas in 1980. Faced with mounting bills, Charles Mapes finally shut down the hotel on Dec. 17, 1982—exactly 35 years after it opened—and handed the keys to his creditors.

The last time I walked through the Mapes was in 1983. I’d been assigned by the Reno newspaper to write about the hotel on the first anniversary of its closing, and the bank trying to sell it arranged a tour. I can recall the strange feeling that I was intruding whenever we entered an empty hotel room and found beds still made and clean glasses on the bathroom counters.

The hotel had a number of unusual design features. The rooms on the corners overlooking the Truckee River were spacious and furnished with antiques, while those in the building’s interior were tiny, with a single small window and a sink. My guide told me that the corner rooms were suites for honeymooners, high-rollers, celebrities, and wealthier guests, while the closet-like quarters were for cowboys who came to town looking for a cheap place to flop after spending most of their paychecks in the casinos and bars.

We wandered up to the Sky Room, where a few dozen glasses were stacked neatly on the counter and bottles of liquor lined the back bar. White tablecloths covered the cocktail rounds, and the stage looked as if it were ready for the next act to come out from behind the curtains. My most vivid memory was the magnificent view of Reno afforded by the Sky Room’s large windows. At the time, I thought the Mapes might have to wait a year or two before a buyer would step forward to fixup the hotel and reopen it. But no one ever did.