A Century of Suffrage

January – February 2020

The 19th Amendment gave women a voice, and an obligation.

BY MEGG MUELLER

In 1910, the penalty for stealing (or kidnapping) a girl in Nevada was five years in prison or a fine of $2,000, while anyone convicted of stealing a horse could be imprisoned for 14 years. At the same time, if a U.S. woman married a foreigner, she lost her citizenship. Another law during the early 1900s, this one concerning community property between a husband and wife, allowed a man to sell or will community property without the consent of his wife. And finally, any wages a woman earned while living with her husband were not deemed her property unless her husband allowed her to use the wages, which were then considered a gift from him.

These are just a few of the laws of the time, shared in the pamphlet “Women Under Nevada Laws,” written in 1913 by Goldfield attorney Bird Wilson. Wilson was concerned at how little women (and men) knew about the rights women had at the turn of the century.

The rancor felt about the above-noted laws being created without any say from female constituents was growing, and the cry of “taxation without representation” was reborn. While that sentiment was enough to ignite the American Revolution, it sparked little fire with the male citizens of the young nation. It took until 1920 before half of the citizens of the U.S. were granted the right to vote. But the fight began long before.

BATTLE BORN CRY

Almost 100 years after the Declaration of Independence was signed, giving the nation freedom from Great Britain, America’s women were still living under tyranny. Susan B. Anthony was arrested in 1872 for voting, and while other women were arrested as well, it was Anthony’s profile as a well-known suffragist that made her a target worthy of setting an example. She was charged with voting for a representative of Congress without having the right to vote. Adding insult to injury, she was declared incompetent to be a witness at her own trial, because she was a woman.

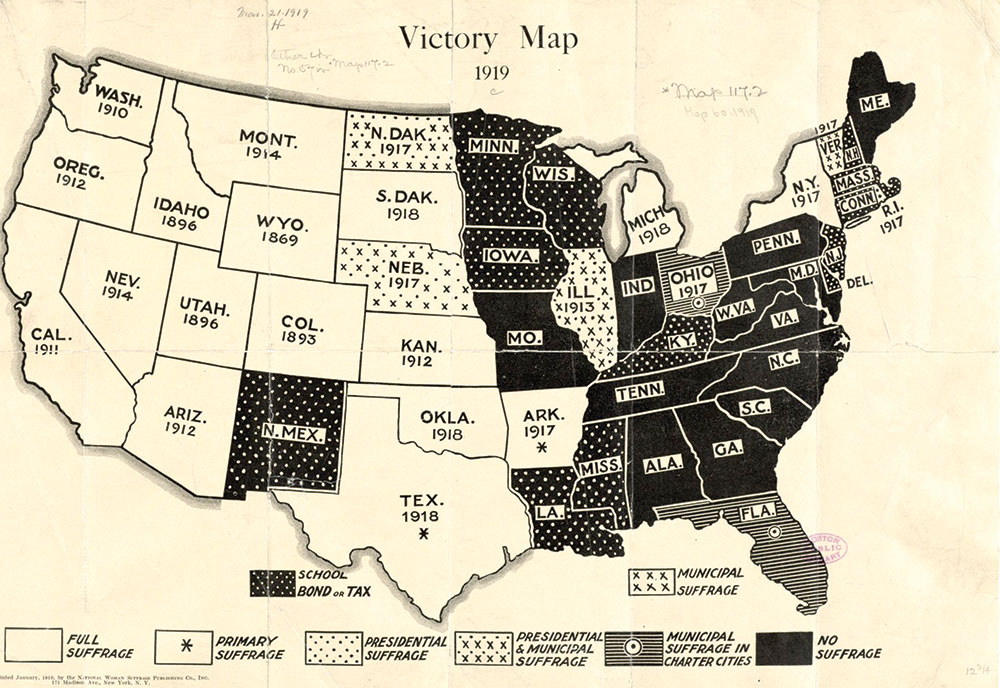

As far back as 1869, when Nevada’s first legislation regarding women’s votes was introduced, the Silver State’s women had been pressing for the right to vote. The issue would return to the Legislature—five times, in fact—but would fail to pass one legislative branch or the other each time, until 1911 when it passed both houses. However, the measure had to pass a subsequent legislative vote in 1913 before it was put before the people for a vote.

Nevadan Anne Martin had recently returned to her home state after a stint in England where she was an active and some say aggressive activist for the feminist cause. Martin had been the founder and first chairman of the Department of History at the University of Nevada but resigned after her father died in 1901. She went to England to study, and it is there she received an activist’s education, even being arrested during a protest.

When she returned to Nevada in 1911, she immediately became active in the Nevada Equal Franchise Society, founded in Reno, and in early 1912 she was named its president. Bird Wilson was vice president, and together, they spent the nine months leading up to the 1913 election blanketing the state with suffrage news, speakers, and lecture tours. Discovering the rural towns were as equally interested as the larger cities, Martin helped societies form in outlying counties, and found women in every town—sometimes just one—to help distribute pamphlets and spread the word about the suffrage movement.

The groundswell in Nevada was largely positive, with more national aversion than local countering the movement. Wilson’s pamphlet saw more than 100,000 copies distributed statewide in two years, and it was seen as very successful in softening the views of many male voters. It also enlightened many women who previously had very little idea what their rights were under the law. The most influential opponent turned out to be banker and miner George Wingfield. So opposed to women voting, Wingfield—who owned the “Reno Evening Gazette”—wrote editorial after editorial against the movement, and once, even threatened to close his mining and ranching enterprises and leave the state if women won the vote.

On election day, Nov. 3, 1914, voters passed the resolution 10,396 to 7,258 with just four counties—Washoe, Storey, Ormsby, and Eureka—voting against it. The negative vote from the four most populous counties proved Martin was right to focus so much attention on the rural voters instead. She’d felt the liquor and gaming interests would have too much sway in the more populated areas, and had seen the anti-temperance movement squash more than one suffrage vote. Raising awareness and culling support in Nevada’s smaller towns, without temperance as an issue, proved a smart move.

THE FEDERAL VOTE

After the Nevada women won the right to vote in state elections, the federal vote was the next target. That year, Martin wrote an article in “Good Housekeeping” magazine, where she stated, “The question we must have answered in the coming campaign is not ‘What shall women do for the political parties?’ but ‘What shall the political parties do for women?’ ”

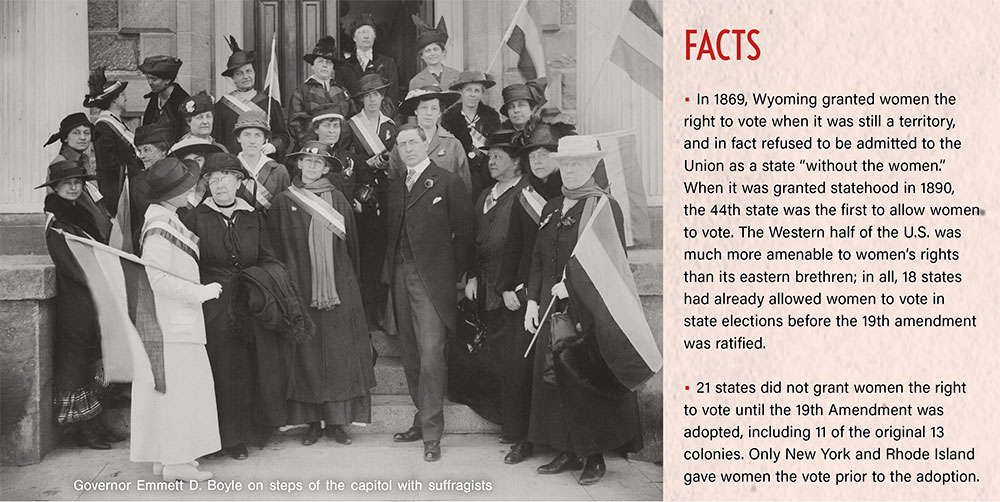

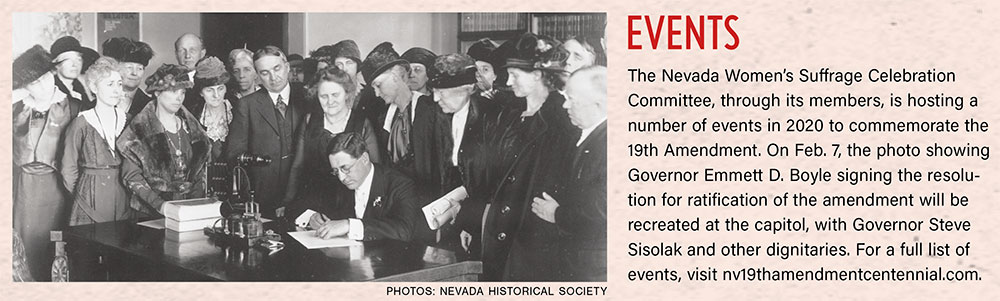

The answer was just what she’d hoped. The 19th Amendment was passed during a special congressional session in summer 1919. It was then sent on to the states for ratification, with 36 states needed to ratify it. The state of Nevada ratified the amendment on Feb. 20, 1920, and Tennessee became the required 36th state when it ratified it on Aug. 18, 1920. The amendment was officially adopted to the Constitution on Aug. 26, 1920.

Women had won the right to vote, but getting them to exercise that right was a struggle. In the first election in 1920, just 36 percent of eligible women voted. Literacy tests, residency requirements, and poll taxes were a few of the reasons that kept women from the polls. It wasn’t until 1960’s presidential election that women voted in greater numbers than men.

Women of color faced even more obstacles when trying to exercise their new right to vote. Black American, American Indian, and Latin women faced state loopholes such as literacy tests and poll taxes, and some had to deal with fraud, intimidation, and even violence when attempting to vote. A group of women in Birmingham, Alabama, were beaten in 1926 when attempting to register to vote. Immigration laws kept Asians from getting citizenship until 1952, but it wasn’t until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 that things really began to change. The Act prohibited racial discrimination in voting, forbidding states from creating discriminatory restrictions.

TODAY’S CAUSE

Inexperience with voting and a lack of education were two of the issues that hindered Nevada’s early women voters, and they are issues that still concern Molly Walt today. Molly is the executive director for the Nevada Commission for Women (NCW) and she is also the chairperson for the Nevada Women’s Suffrage Celebration Committee which is dedicated to “educating Nevadans on the suffrage movement and the historic importance of the ratification of the 19th Amendment.”

The two organizations are held together by Molly’s leadership and the united goal of education about suffrage, and women’s equality issues today. Molly became the NCW’s leader two years ago, and the committee sprang from her research about plans for celebrating the 19th Amendment’s 100th anniversary.

“No one had a set-in-stone plan, which made me decide to form a statewide committee where we could all work together to coordinate events,” Molly explains. “We want all these events to be successful. We need to celebrate the 70-plus years that it took to get women the right to vote.”

The NCW was created as an information clearinghouse in 1991, and while it was dormant for a few years, it was reactivated in 2014 by Governor Sandoval. Its purpose is to advance women toward full equality, in all areas, and to Molly that goal starts with educating people about how far women still have to go to attain equality. Correcting gender disparity is a main goal, but so is creating awareness about how—despite 100 years since the vote was passed—the role of women in leadership still needs to be addressed.

Women often won’t apply to boards and leadership committees if they don’t feel qualified, Molly claims, while men apply to what interests them and let the interviewer decide they are qualified. It might seem a small distinction, but it can keep women from seeking opportunities in which they may be successful. The socioeconomic factors that influence women are another area the NCW studies, along with providing advice to legislators on the effect of proposed legislation on women. Keeping the media informed about women’s issues, and recognizing and promoting the contributions women in the state make is also important to the commission, as is educating young people about how far women’s rights have come, and how far they still have to go. As a former teacher and mother of four, it’s the education component that keeps coming back to the forefront for Molly.

“My daughter is a senior in high school, and she spent one day learning about women’s suffrage,” Molly says. “This is important to me because of my daughters; my kids. Women aren’t treated equally, they often aren’t paid equally, and the opportunities aren’t equal.”

There are studies that show it could be another 60 years for women to be paid the same as men, Molly says, and her concern is that the right to vote is being taken for granted.

“Change still needs to happen,” she says. “I just want my daughters to be given the same opportunities, and I want to be part of that change. So this year, we celebrate the women who did fight for those opportunities.”

LEARN MORE

–

Nevada Commission for Women

515 E. Musser St, Ste. 303

Carson City, NV 89701

admin.nv.gov/commissionforwomen, 775-684-0296

–

Nevada Women’s Suffrage Celebration Committee

nv19thamendmentcentennial.com, 775-684-0296