Law, Order, and a Game of Chance

March – April 2016

Law, Order, and a Game of Chance

THE EARP BROTHERS SEEK THEIR FORTUNES IN NEVADA.

THE EARP BROTHERS SEEK THEIR FORTUNES IN NEVADA.

BY RON SOODALTER

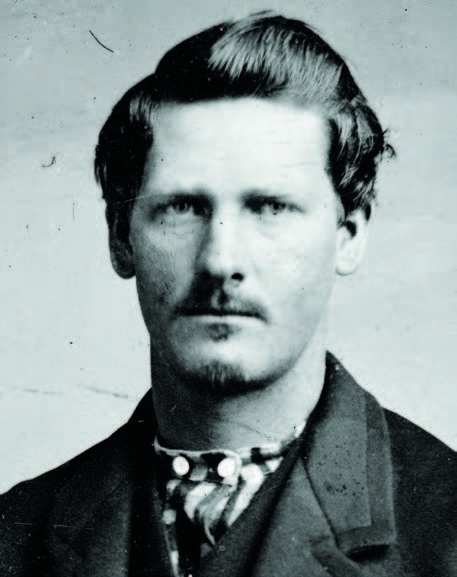

Life in the Old West—Hollywood notwithstanding—was often mundane. The deadly gunfights and daring hold-ups were comparatively few. Yet, certain names have attained legendary status, selling countless books and millions of theater tickets, while the reality was considerably less exciting. No two figures attempted to live quieter lives, yet were haunted by largely undeserved reputations, than brothers Wyatt and Virgil Earp, as their sojourn in Nevada would prove.

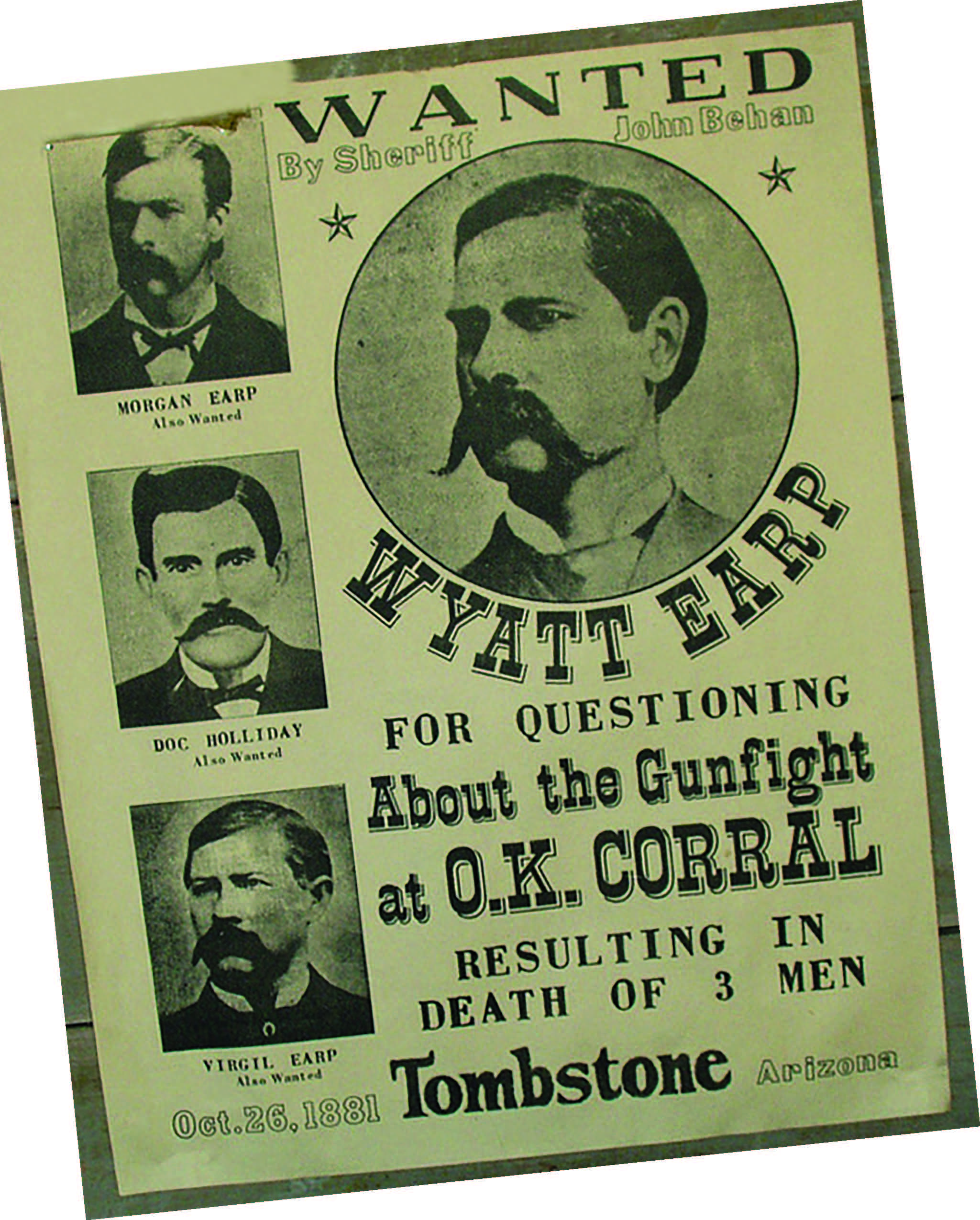

As with many in the West of the late 1800s, Wyatt and Virgil were basically drifters—sometime gamblers, sometime lawmen, middling businessmen, wannabe politicians—searching for the big payoff. Yet they would always be defined by a 30-second shootout that left three men dead, and would result in the assassination of younger brother Morgan and the crippling of Virgil. Wherever they went, the gunfight at the OK Corral would cast a long shadow, and well into the 20th century they would be known as the “Earps of Tombstone.” History took a backseat to hype, and the legend always preceded and haunted them.

As with many in the West of the late 1800s, Wyatt and Virgil were basically drifters—sometime gamblers, sometime lawmen, middling businessmen, wannabe politicians—searching for the big payoff. Yet they would always be defined by a 30-second shootout that left three men dead, and would result in the assassination of younger brother Morgan and the crippling of Virgil. Wherever they went, the gunfight at the OK Corral would cast a long shadow, and well into the 20th century they would be known as the “Earps of Tombstone.” History took a backseat to hype, and the legend always preceded and haunted them.

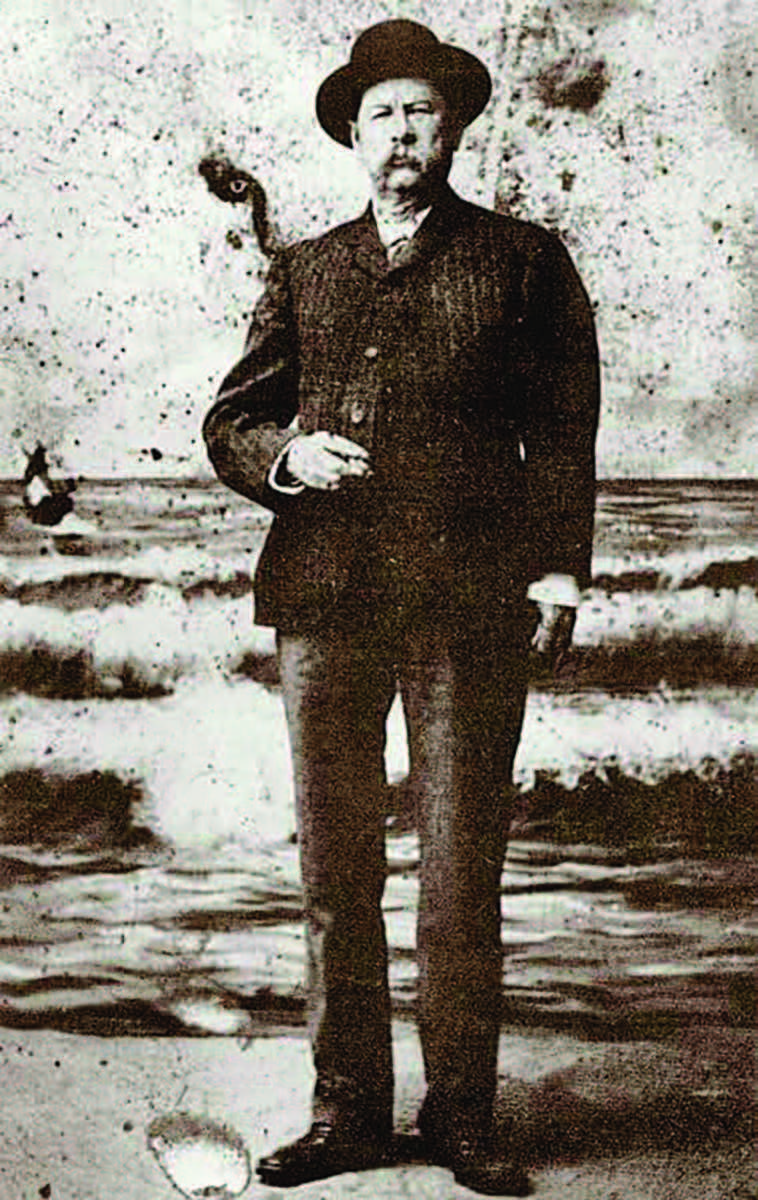

The two restless brothers devoted most of their adult lives to the quest for fortune in deserts and boomtowns from Kansas to California, Arizona to Alaska. Nearly a quarter of a century after the gun smoke had settled over the streets of Tombstone, they found themselves in Nevada, seeking the riches that somehow always eluded them. They each followed a circuitous route, occasionally coming together, but often going separate ways.

TONOPAH’S RICHES BECKON

Wyatt heard about the Nevada gold strikes while living in Los Angeles. He and his wife, Josephine, had recently returned from an extended trip in Alaska, where for the first and only time, he had prospered. They moved to Tonopah in January 1902, two months shy of Wyatt’s 54th birthday. The couple soon discovered, however, that the initial boom was over. Unemployment was high, and many residents had moved on. Further exacerbating matters, the Earps were greeted on their arrival by a two-week blizzard.

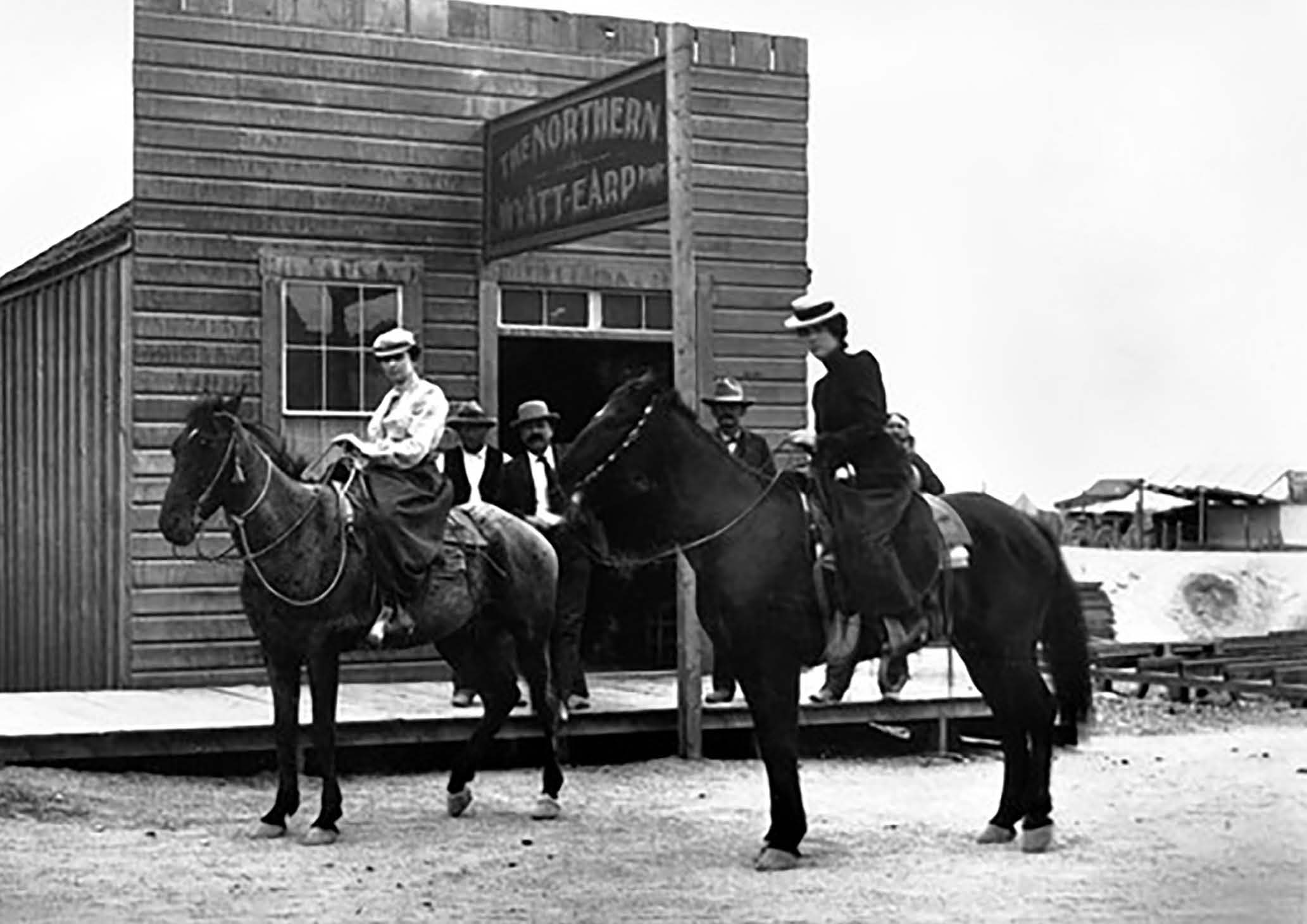

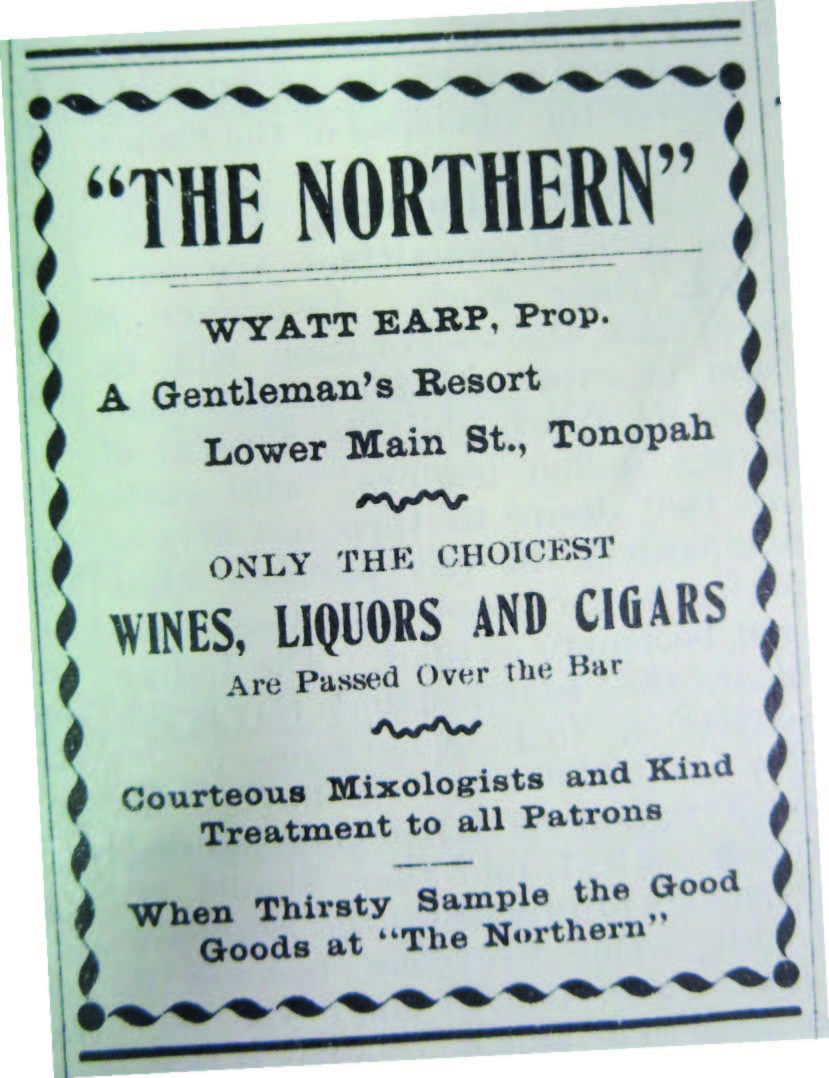

Nonetheless, Wyatt elected to make a go of it in Tonopah. He fulfilled multiple functions, serving as U.S. deputy marshal and head of a private “police force,” while running a saloon: The Northern. Wyatt’s reputation as a gunfighter had preceded him, and his name on the saloon sign served to attract business.

Local mining interests had formed the private police force for the express purpose of discouraging claim jumpers, and the founders immediately sought out the storied Wyatt Earp as its leader and figurehead. Mindful of Wyatt’s reputed history, mining engineer John Hammond told him, “You will not shoot except in self-defense.” Earp agreed, but reportedly stipulated, “I must be the judge of when the self-defense starts.” Due in large measure to the weight that his name carried, there were no shooting incidents under his watch.

Wyatt also hauled silver ore from the Tonopah Mining Company to the Carson and Colorado Railroad depots at Sodaville and Candelaria. When he wasn’t tending to business, he and Josephine were off prospecting, hunting for the elusive strike that was always over the next hill or in the next stream. As one old friend recalled years later, “He was a prospector at heart; he loved to be around miners.”

As ever, Wyatt’s reputation followed him, and unfounded stories periodically appeared in local and out-of-state newspapers. Responding to one fabricated tale titled “The Taming of Wyatt Earp, Bad Man of Other Days,” the usually taciturn Wyatt wrote to the editor, complaining that the article “does me an injustice…. [N]either I nor my brothers were ever ‘bad men’….We have been officers of the law….” Still, people generally chose to believe the wild stories.

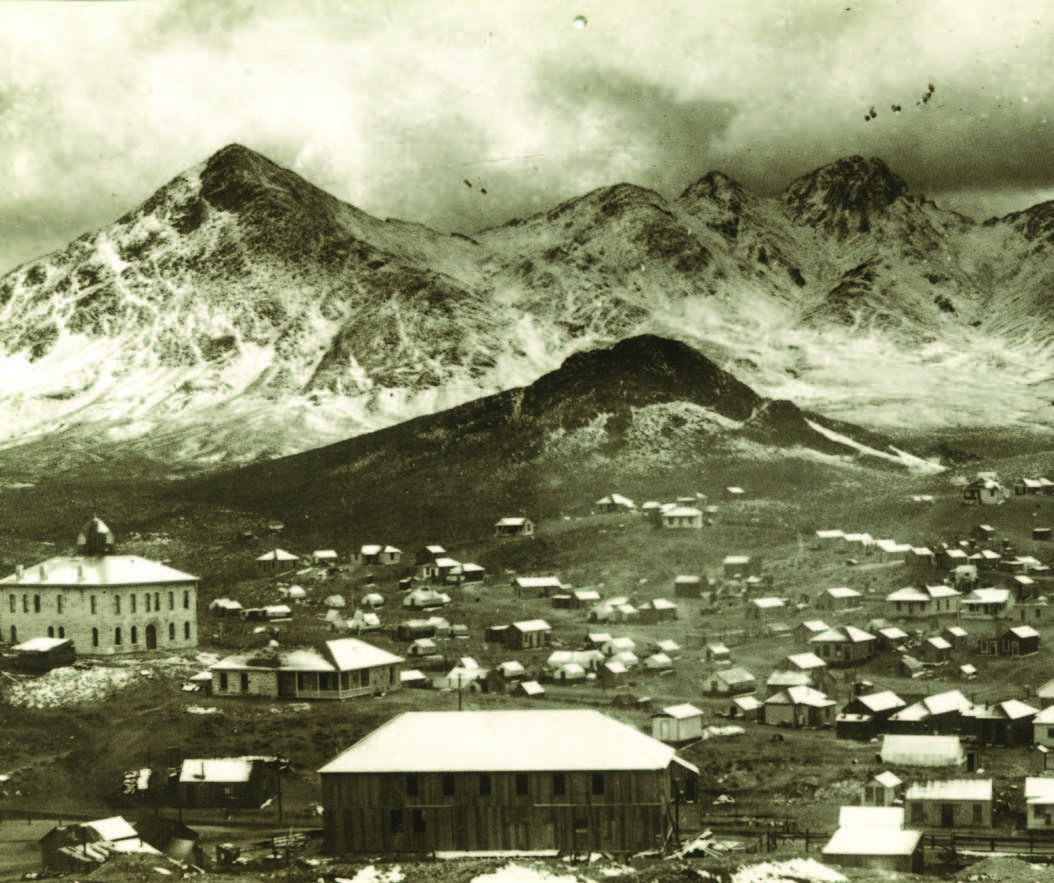

GOLDFIELD UNTIL THE END

Meanwhile, in mid-1904, Virgil and his wife, Allie, made their way to Goldfield and the most recent of the big strikes. However, Virgil arrived too late and with too little capital to establish himself as a force in the rawboned community. So he did what the Earp brothers had always done when their reserves ran low: He became a lawman. On Jan. 26, 1905, Virgil was sworn in as an Esmeralda County deputy sheriff. He was also named a “special officer,” serving in the National Club—a lively Goldfield saloon. The job title masked the fact that he was basically a glorified bouncer. The Tonopah Sun reported on his appointment as peacekeeper in the popular watering hole, labeling him “one of the famous family of gunologists.”

By then, Virgil was 62 years old and had suffered several broken bones in an Arizona mine cave-in, as well as the crippling wounds received in Tombstone; but at a powerful 6-foot-2-inches tall—even with only one functional arm—he was a force to be reckoned with. In the fall, however, Virgil’s health took a sharp downturn. A pneumonia epidemic swept through Goldfield and it put him in the hospital. According to Allie’s memoirs, he said, “Light my cigar, and stay here and hold my hand.” They were his last words. Virgil died on Oct. 19, 1905.

In one obituary, under the heading, “Makes Final Camp,” the Goldfield News editor referred to Virgil as a “quiet unassuming man” who “endeared himself to all who knew him,” but couldn’t resist adding that “all of the Earp Boys would fight at the drop of a hat.”

The Nevada State Journal followed a harsher tack. In a column titled, “Virgil Earp, Gunfighter, Cashes In,” it attempted levity: “It speaks well for Goldfield that Mr. Earp was permitted to go hence with his boots off, and that he took no fellow citizen of that enterprising burg with him on his long voyage to that undiscovered country where firearms and bowie knives are reasonably presumed to constitute a merely negligible quantity….” Virgil, whose career as a respected lawman had rarely erupted in violence, deserved better.

WYATT MOVES ON; THE STORIES DO NOT

In late summer 1903, Wyatt sold his interests, and he and Sadie left Tonopah. They spent the next few years prospecting in the desert around Silver Peak, Esmeralda County, and wintering in Los Angeles. They staked three claims in the Palmetto Mountains, and although they came tantalizingly close a time or two, they never struck it big. Finally, they returned to Los Angeles for good, where they lived in what one biographer referred to as genteel poverty. Wyatt lived until Jan. 13, 1929, dying at the age of 80, all the while trying unsuccessfully to set the historical record straight.

In late summer 1903, Wyatt sold his interests, and he and Sadie left Tonopah. They spent the next few years prospecting in the desert around Silver Peak, Esmeralda County, and wintering in Los Angeles. They staked three claims in the Palmetto Mountains, and although they came tantalizingly close a time or two, they never struck it big. Finally, they returned to Los Angeles for good, where they lived in what one biographer referred to as genteel poverty. Wyatt lived until Jan. 13, 1929, dying at the age of 80, all the while trying unsuccessfully to set the historical record straight.

Wyatt’s brief adventure in Nevada, as elsewhere, inspired stories among the locals both before and after his death. One tale—published in a 1932 book of old-timers’ recollections—has him driving off a gang of claim jumpers simply with the mention of his name. (“And who in hell are you?” “I’m Wyatt Earp.” “Oh!” And without further ado the claim jumpers moved out, swiftly and completely.) The story lists various former associates of Wyatt, “such big shots of the frontier as Wild Bill Hickok…and Jim Bridger….” In fact, there is no evidence that Wyatt ever met either man.

In 1968, Mrs. Hugh Brown—who had lived in Tonopah decades earlier—published her reminiscences in “Lady in Boomtown,” which contains another iteration of the same story. In her version, Wyatt is “a young man who had just come into town…. He was a fancy crack shot.” Wyatt, who is being paid $20 per day to maintain order, drives off the claim jumpers after the sheriff proves incapable. Mrs. Brown quotes the mining supervisor: “I never spent money more effectively.”

Another report of the claim-jumping incident was published in the Tonopah Miner of Aug. 15 and Aug. 22, 1902, at the time it actually occurred. In a detailed account that spanned two issues, it fails to mention Wyatt Earp at all. As it turns out, the first printed mention of Wyatt’s participation in the affair did not occur until Jan. 13, 1929—two days after his death. The Tonopah Daily News ran a story based entirely on interviews with various old-timers, whose memories appear to have been impacted by the Old West maxim: “If you can’t improve on a story, it ain’t worth tellin.'”

A story that paints Wyatt in a less favorable light ran in the Tonopah Sun several years after the Earps had left. It recounted a supposed incident in which the local sheriff, Thomas Logan, disarmed a drunken Wyatt, who was brandishing a brace of pistols, intent upon shooting a young miner. No account of such an incident appeared in the local news at the time.

The stories surrounding the Earp brothers—especially Wyatt—are almost all apocryphal. The truth was much less hair-raising. From their first foray West as young men to their final outing in the deserts of Nevada, the Earps were no different than so many of their contemporaries—men “on the make,” in a raw and often inhospitable land. In the words of one chronicler of the Earps’ Nevada sojourn, “The cumulative evidence shows them to be ordinary men doing ordinary work.” No brawls, no gunfights; just two aging brothers striving to succeed in a West that was rapidly passing them by.