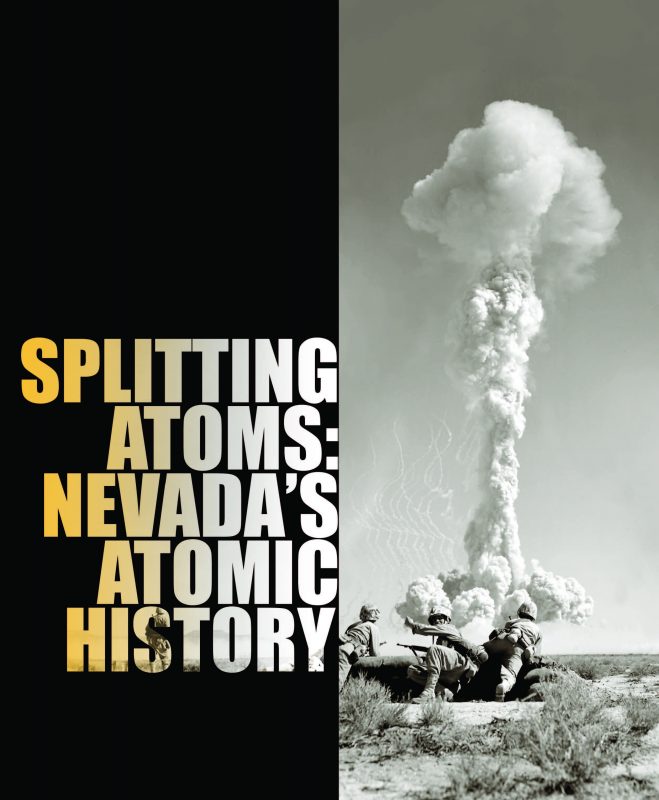

Splitting Atoms: Nevada’s Atomic History

March – April 2017

Atomic testing is remembered as a sensational and sometimes sinister era of the state’s history.

BY ERIC CACHINERO

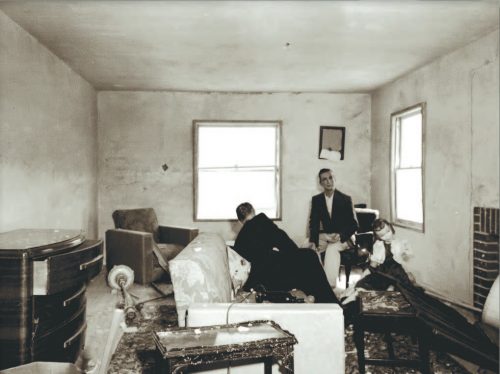

On the morning of May 5, 1955, a family nested in their contemporary dream home. A tall redbrick chimney and lovely shutters complemented the whitewashed exterior, which gave an exquisite view of the surrounding desert mountains. The home was perfect in nearly every way: a state-of-the-art television, an immaculate kitchen, dining room laden with fresh and frozen food, and the family Desoto sedan parked outside. The occupants were the quintessential 1950s household: a husband, wife, and several fine children, and on that morning they had numerous guests scattered about. Though they had some neighbors’ houses not too far away, the small town they lived in was mostly quiet.

On the morning of May 5, 1955, a family nested in their contemporary dream home. A tall redbrick chimney and lovely shutters complemented the whitewashed exterior, which gave an exquisite view of the surrounding desert mountains. The home was perfect in nearly every way: a state-of-the-art television, an immaculate kitchen, dining room laden with fresh and frozen food, and the family Desoto sedan parked outside. The occupants were the quintessential 1950s household: a husband, wife, and several fine children, and on that morning they had numerous guests scattered about. Though they had some neighbors’ houses not too far away, the small town they lived in was mostly quiet.

But this morning was different than most. Just as the faintest hints of sunlight shone across the desert sky, anomalies abounded. As the father peered out the window, in a split second he saw a blinding flash, followed by an inferno, and finally the sights and sounds of unfathomable destruction. As luck would have it, the family and all of their guests survived the blast, as mannequins tend to do.

The mannequin family had witnessed—just several thousand feet from ground zero—one of man’s most destructive inventions: the atomic bomb. Though many of their neighbors’ homes weren’t so lucky, several that were constructed for the Apple II blast, theirs included, remained standing. The 29-kiloton (roughly 29,000 metric tons of TNT) device was detonated from a 500-foot tower on Yucca Flat at the Nevada Test Site, now known as the Nevada National Security Site (NNSS). Though Apple II wasn’t the first atomic bomb test at the site, it joined 927 others as part of Nevada’s captivating and sometimes chilling atomic legacy.

BOMB BUSINESS IS BOOMING

The atomic bomb played a vital role in the outcome of WWII, and though the war ended in 1945, the interest of the U.S. in this new technology was burning brighter than ever as the Cold War took shape. From June 1946-48, atomic testing took place at several Pacific island sites, including Bikini and Enewetak Atolls; however, it became costly and difficult to perform them so far from home. Cue Project Nutmeg—a top-secret feasibility study conducted by the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) to identify the best possible location for a mainland atomic test site.

After a meticulous search, an area was selected 65 miles northwest of Las Vegas due to government control of the land, low population, little annual rainfall, and its absolute vastness. On Dec. 18, 1950, President Harry S. Truman signed the order to establish the site, and a little more than a month later the first atmospheric test took place. The 1-kiloton bomb named Able dropped from a plane onto Frenchman Flat.

After the blast proved successful, the AEC decided to expand facilities, and the site’s operation center at Mercury—located just 5 miles from U.S. Route 95—was born. In the heyday of atomic testing, Mercury boasted 10,000 workers daily, and held many comforts including dormitories, health facilities, a steakhouse, and even an Olympic-sized swimming pool.

Members of the 11th Airborne Division kneel as they watch a test in 1951. Photos reprinted from “Images of Amercia: Nevada Test Site: By Peter W. Merlin (Arcadia Publishing, 2016)

FIRE ON THE TUBE, CLOUDS ON THE HORIZON

Atmospheric testing was extensive in the early days, and the AEC dreamt up countless designs and scenarios to better understand the bomb’s impact on various materials. Many of the tests took place at the 5.8-square-mile dry lakebed called Frenchman Flat. Bomb shelters, man-made forests, utility lines, a railroad trestle, a bank vault, and even mock towns outfitted with mannequins were constructed to test how they stood up to atomic blasts. Civil defense tests were also conducted several miles north on Yucca Flat.

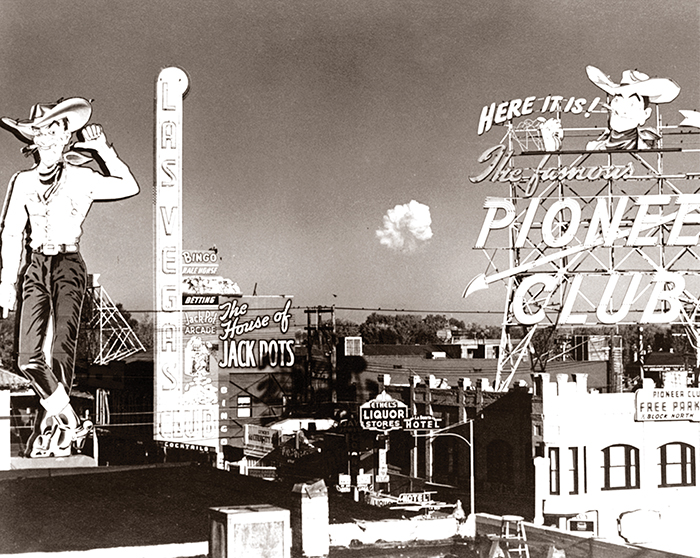

Nevada Magazine’s inaugural editor, Fred Greulich, was in attendance with those who watched a 16-kiloton bomb named Annie detonated at the test site on March 17, 1953. The test—part of the Operation Upshot-Knothole projects—was the first nationally televised atomic detonation in history and featured the destruction of several mock structures. Approximately 600 journalists and cameramen from across the U.S. gathered to view the blast, which was broadcast to about 15 million viewers. Their vantage point for tests on Yucca Flat became known as News Knob, and the famous location was used to broadcast the U.S.’s muscle to the world. Greulich wrote in the June-December 1953 issue, “Primarily…the explosion was a scientific experiment, but secondarily it was for the purpose of impressing Americans with the deadly seriousness of nuclear device detonations and the need for arousing a keener interest in civilian defense.”

The explosions weren’t only visible by high-ranking officials, newsmen, and on television, though. Las Vegas became the epicenter of atomic displays. Nighttime flashes and mushroom clouds were sometimes visible from the city and could be viewed from hotel rooms, rooftops, and sometimes simply from the street. Visitors and residents could often feel the ground shake, and occasionally had to deal with rattling, sometimes shattering windows. The brilliant, unbeknownst radioactive, clouds didn’t last too long, though.

DRILL FOR THRILL

After a total of 100 aboveground atomic tests, the Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963 prohibited atmospheric, outer space, and underwater testing, bringing the days of visible mushroom clouds to a close. The treaty did not, however, limit underground testing. Instead of delivering the atomic weapons via airplane, cannon, or tower—as happened in aboveground tests—holes were drilled and atomic bombs were lowered into them and detonated. Most of the underground tests took place at Yucca Flat.

Initially, underground testing proved difficult and time-consuming. A 1,000-foot-deep, 36-inch diameter hole could take up to 60 days to drill, and sometimes holes needed to accommodate devices that were 6-12 feet in diameter. New drilling equipment and technology was developed, and soon the underground tests were in business.

Unlike atmospheric tests that cause scorched earth but didn’t displace much dirt, underground tests created craters—big ones. Once the atomic device was lowered by crane into underground shafts, the hole was filled in with sand, gravel, and epoxy, and the device detonated remotely. Information was then collected and delivered via fiber optic diagnostic cables to aboveground unmanned trailers, which monitored the effects of the bomb extremely carefully and accurately.

The intense heat from underground explosions caused surrounding rock to liquefy instantly, resulting in a hollow cavern. After time, the roof of the blast cavern collapses, causing the earth above it to implode on the hollow structure, leaving a massive subsidence crater on the surface of the earth.

Underground testing also provided scientists and engineers opportunities to explore new, peaceful purposes for atomic devices. For example, tests were conducted to determine the ability of atomic explosions to excavate earth and rock to create canals, harbors, and other large-scale excavations. One such test left behind the Sedan Crater, which is perhaps the most impressive crater at the test site, measuring 300 feet deep and 1,300 feet in diameter.

From 1957-1992, 828 underground atomic tests (928 total atomic tests including atmospheric) were conducted, and much was learned about the way the devices act and perform under a host of different conditions. In 1992, President George H. W. Bush introduced a moratorium on atomic weapons testing, effectively putting an end to full-scale testing. The NNSS, though, remains a bastion of national security to this day.

NEVADA NATIONAL SECURITY SITE

In 2010—to better represent the nature of the work occurring at the site—the Nevada Test Site was renamed the Nevada National Security Site. Operated by the U.S. Department of Energy. The 1,360-square-mile NNSS utilizes the world’s most advanced technologies, with a focus on keeping the country’s nuclear deterrents safe, secure, and effective. The site supports homeland security and counterterrorism operations, including nuclear detection systems and first-responder training. NNSS Public Affairs Manager Dante Pistone says much of the national security work that occurs at the site today is only possible because of the past.

“The foundation for much of this work was laid during the nuclear testing days,” he says. “Many of the lessons we learned back then are applied today without having to do actual testing. Instead, we work with the National Laboratories to support maintenance of the nation’s nuclear deterrent using subcritical experiments and computer models.”

Some of the active programs at NNSS today include:

• Joint Actinide Shock Physics Experimental Research (JASPER): JASPER is one of the most powerful gas guns on the planet. It is designed to subject materials—including plutonium—to extreme pressures and temperatures to see how they react without the need for underground nuclear testing. The gun is capable of accelerating projectiles at 28,000 feet per second.

• Device Assembly Facility (DAF): DAF allows scientists to work on special nuclear material in a controlled environment. The facility deals with subcritical tests and computer models to further understand what happens when a nuclear device is detonated.

• Big Explosives Experimental Facility (BEEF): This remote facility is used to test conventional high explosives and measure their responses using high-speed optics and x-ray radiology.

• Remote Sensing Laboratory (RSL): RSL focuses on emergency response technologies, counterterrorism, and radiological incident response. Teams are in place 24/7 to respond to nuclear-related threats worldwide.

• T-1 Training Area: Located on ground zero of a 1950s-era atmospheric atomic test, the T-1 Training Area provides one of the most realistic radiological training environments anywhere, testing first responders in a number of different challenging radiological scenarios. The area includes mock storefronts, a crashed 737 airliner, helicopter, trucks, busses, and a derailed locomotive.

• Nonproliferation Test and Evaluation Complex (NPTEC): NPTEC is the largest facility for open-air testing of hazardous toxic materials and biological stimulants in the world. The facility provides field-testing and sensor testing to improve responses to toxic chemical spills, in full compliance with all applicable federal and state environmental requirements.

• U1a Complex: The U1a Complex is an underground experimental facility designed to conduct subcritical experiments, like measuring properties of plutonium under weapon-like conditions. The plutonium is subjected to high pressures and shocks, mimicking conditions during an atomic explosion.

Beyond tests concerning hazardous or explosive materials, NNSS has served as the location for other historic activities. In 1969, astronauts including Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin underwent lunar training at the site. The mission involved collecting geological material and operating moon rovers. In addition, the University of Nevada, Reno; University of Nevada, Las Vegas; and the Desert Research Institute have used the site for climate testing. Experiments involved testing the effects of climate change on the landscape by exposing it to increased CO2 levels.

AN ERA ELEVATED

Nevada’s nuclear history is remarkable. It is sensational to some, and sinister to others. The truth is, there is so much we have learned—and continue to learn—from this technology. Given that most people have never had the fortune or misfortune of witnessing an atomic blast firsthand, Greulich, a man who has, explained it best. “All of the blasts are frightfully terrible yet unbelievably magnificent; they are hellish but beautiful; horrible yet spectacular. The whole range of human emotion is brought into play upon observing such a detonation.”