Snowshoe Thompson

March – April 2018

SNOWSHOE THOMPSON – HERO OF THE SIERRAS

Post and promises, legendary mail carrier always delivered.

BY BRANDON WILDING

“Most remarkable man I ever knew, that Snowshoe Thompson. He must be made of iron. Besides, he never thinks of himself, but he’d give his last breath for anyone else—even a total stranger.”

—S.A. Kinsey, Genoa Postmaster

EN LEGENDE ER F∅DT (A LEGEND IS BORN)

Jon A. Torsteinsson Rue was born on the Rue Farm in Tinn, Telemark, Norway, April 30, 1827. He was born to father, Torstein Olsson Gallo, and mother, Gro Jonsdatter Einungbrekke, and was the youngest of his father’s 14 and his mother’s six children. Tor-stein was 68 when Jon was born and died two years later, leaving Gro to care for the family on the farm. She raised Jon as best she could in the mountains of Norway, but the long Norwegian winters and the wet summers of Telemark made farming difficult and the family struggled to make ends meet.

Jon A. Torsteinsson Rue was born on the Rue Farm in Tinn, Telemark, Norway, April 30, 1827. He was born to father, Torstein Olsson Gallo, and mother, Gro Jonsdatter Einungbrekke, and was the youngest of his father’s 14 and his mother’s six children. Tor-stein was 68 when Jon was born and died two years later, leaving Gro to care for the family on the farm. She raised Jon as best she could in the mountains of Norway, but the long Norwegian winters and the wet summers of Telemark made farming difficult and the family struggled to make ends meet.

In spring 1837, Gro along with Jon—now age 10— set sail for America. After two and a half difficult months at sea, they reached New York on August 15. Upon their arrival, Gro would change their name to the more American moniker, Thompson. Historians believe that she chose Thompson simply because it was similar to Torsteinsson. Jon also took the Americanized spelling of his first name. For the next 14 years, John would travel around Illinois, Missouri, Iowa, and Wisconsin.

GO WEST, YOUNG MEN

In 1851, news of the California gold discovery reached John and he decided to make his way west with his half-brother, Thore. The two men drove a herd of cattle from Wisconsin to California. The trip west was a hardship for many pioneers, but not for John. He loved the adventure and found comfort in the challenges that lay beyond each horizon.

Like many others who traveled to the gold fields, John was disillusioned by dreams of riches. He spent a few years trying his luck, but always came up empty handed and would soon return to the life he had previously known. Ranching had always come easy to him, so he rented land along Putah Creek outside Sacramento and began to work the land. However, John missed living in the mountains that reminded him of Norway. In fall 1855, John would find his escape back to the mountains in an article in the “Sacramento Union.” The article requested a mail carrier that could carry the mail between Placerville, California, and Genoa during the harsh winter months, stating: “People Lost to the World; Uncle Sam Needs a Mail Carrier.” The heavy snows and cold cut off communication for the people west of Salt Lake City and east of the Sierras from the rest of the world. A few brave men previously tried to do the job, but frozen limbs and death hindered success.

FASHIONING THE FUTURE

John did not fear getting lost in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He considered them a narrow range and claimed that any man who kept his wits about him could make his way out. He is quoted as saying, “If a man is lost in the mountains, he should not wander uphill and downhill at random. By going steadily downhill he will eventually come to a stream which will lead him to civilization.”

John did not fear getting lost in the Sierra Nevada Mountains. He considered them a narrow range and claimed that any man who kept his wits about him could make his way out. He is quoted as saying, “If a man is lost in the mountains, he should not wander uphill and downhill at random. By going steadily downhill he will eventually come to a stream which will lead him to civilization.”

John would return to his roots and adopt a Norwegian form of transportation as a means of travel over the mountains. He began crafting a pair of snow skates out of straight pieces of oak. After cutting them into 4-inch wide, 10-foot long planks, he soaked the ends, steamed them, and then began bending and carving them into crude skis. There were other Norwegian communities in the west that were using similar snowshoes, but none were more famous than John for bringing this form of transportation to America.

With leather straps holding his feet to the skis and a staff in his hands for balance, he began practicing in the mountains around Placerville. He also spent some time talking to people who were familiar with the mountains, so he could prepare for any problems that he may encounter. After a few weeks of practice, he made his way to Placerville and offered his services to the postmaster.

LIONHEART

In January 1856, John began his first trip over the mountains to Genoa. As he was leaving town, it is rumored that someone yelled out, “Good luck, ‘Snowshoe’ Thompson!” A new name and a legend were born. On a trip that took other men weeks, if they made it at all, Snowshoe made it from Placerville to Genoa in three days and returned in two. The 90-mile trip was often covered with 30 to 50 feet of snow and Snowshoe’s bag often weighed 80-90 pounds. When blizzards would rage through the Sierras, he would simply find a flat rock and dance Norwegian folk dances until the storm passed.

For the next 20 years, Snowshoe Thompson would carry the mail to the people of Genoa, but he was so much more than a mailman. He often purchased things for the people of the community whether they could pay him or not. He once skied 400 miles in 10 days to save a man’s life. He believed in his community and he loved the country that had become his home.

VENDER HJEM (RETURNING HOME)

On May 15, 1876, Snowshoe Thompson looked at his son and said, “Always be a good boy, Arthur. Mind your mother and be good to her.” Those would be his final words before he succumbed to appendicitis that had developed into pneumonia. He died at his home in Diamond Valley—located about 10 miles south of Minden just over the California border—that he had farmed and loved for 17 years. John spent his whole life caring for the people around him and even in his final moments his love for family was evident.

SNOWSHOE VS. IRON HORSE

In the months leading up to January 1872, John had been petitioning Congress for $6,000 in back pay that many believed was owed to him. After not receiving any response from Congress, he followed the advice of one of his friends and decided to go to Washington D.C. and meet with anyone who would listen to his request.

In the months leading up to January 1872, John had been petitioning Congress for $6,000 in back pay that many believed was owed to him. After not receiving any response from Congress, he followed the advice of one of his friends and decided to go to Washington D.C. and meet with anyone who would listen to his request.

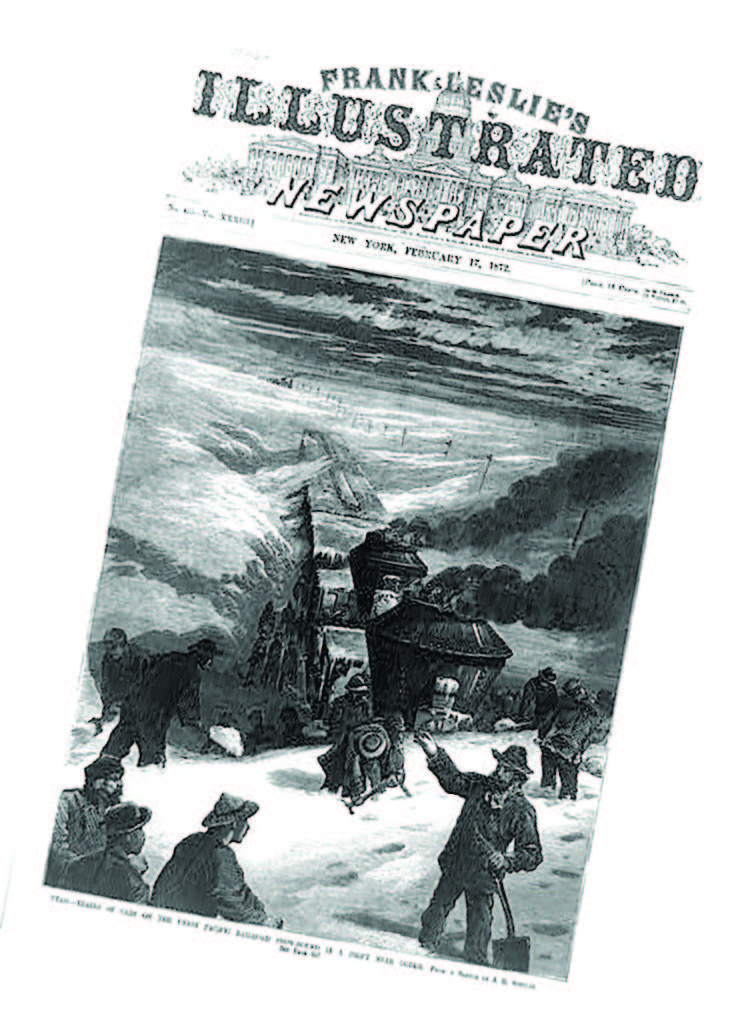

John boarded a train in Reno on January 17 and headed east. However, three days later, 35 miles west of Laramie, Wyoming, the train became stuck in a snowstorm and soon the heavy snowdrifts halted the trip. The men onboard spent a day trying to set the locomotive free with shovels, but the heavy winds continued to block the tracks. Four locomotives were then brought in to try and free the train, but to no avail.

John gave the following report to Dan DeQuille regarding the trip: “It was on Sun-day that the four engines were tried and “found wanting.” On Monday morning the wind was still blowing a gale, and the snow was still drifting badly.”

Coming to the conclusion that the train would not be moving for a few days, John and a fellow passenger, Rufus Turner, decided to make their way to Laramie on foot. A few miles west of Laramie the two men found another train, but the fate of that train was much like the one that they had been on a day earlier. Turner soon gave up on walking and stayed in Laramie, but John was determined to continue his trip to Washington D.C. Through wind and snow in temperatures that fell 15 to 35 degrees below zero, John continued another 56 miles to Cheyenne. There he would find a train free of the snow and continue his journey. Upon arriving in Washington D.C., John’s story of his trip spread around the nation’s capital. A local newspaper would retell his journey and declare that he was the “first man who had ever beaten the ‘iron horse’ on so long a stretch.”

SNOWSHOE THOM(P)SON A TRUE PIONEER

“…There ought to be a shaft raised to Snow-Shoe Thompson; not of marble; not carved and not planted in the valley, but a rough shaft of basalt or of granite, massive and tall, with a top ending roughly, as if broken short, to represent a life which was strong and true to the last. And this should be upreared on the summit of the mountains over which the strong man wandered so many years, as an emblem of that life which was worn out apparently without an object…”

“…There ought to be a shaft raised to Snow-Shoe Thompson; not of marble; not carved and not planted in the valley, but a rough shaft of basalt or of granite, massive and tall, with a top ending roughly, as if broken short, to represent a life which was strong and true to the last. And this should be upreared on the summit of the mountains over which the strong man wandered so many years, as an emblem of that life which was worn out apparently without an object…”

Attributed to: Dan Dequille,

Territorial Enterprise, May 19, 1876.

Dedicated this 10th day of July 1977,

as founded and endorsed Bicentennial Project,

by the Nevada members of the

Ancient & Honorable Order of E Clampus Vitus

Four days after his passing, Comstock journalist Dan DeQuille would write the following in the “Territorial Enterprise:”

Four days after his passing, Comstock journalist Dan DeQuille would write the following in the “Territorial Enterprise:”

“…There ought to be a shaft raised to Snow-Shoe Thompson; not of marble; not carved and not planted in the valley, but a rough shaft of basalt or of granite, massive and tall, with a top ending roughly, as if broken short, to represent a life which was strong and true to the last. And this should be upreared on the summit of the mountains over which the strong man wandered so many years, as an emblem of that life which was worn out apparently without an object…”

No man sums up the spirit of the American West more than Snowshoe Thompson. He was a self-made man that took care of his family and the people in his community. He had a heart of gold that far outweighed any of the gold taken out of the mountains that he conquered. His spirit and love for his fellow man will forever shine down through the trees and reflect off the snows of the Sierras.