Yesterday: Will James & a Horse Called Happy

March – April 2018

BY ANTHONY AMARAL

Originally appeared in the May/June 1980 issue.

When Will came to Reno he was just another drifting cowboy, broke and out of a job. His future as the author and illustrator of Smoky, the classic story of a cow pony, and 15 other books of the range country had not yet become top card in his deck. But grazing in a pasture outside Reno was a black gelding named Happy. He was a bronc, and his role was to change the course of the young cowboy’s life.A few months after the close of World War I, a lean and taciturn cowboy came to the town of Reno, Nevada. His name was Will James, and he had ridden a meandering route from the desert country of southern Nevada. His name, back then, didn’t attract any public attention. Cowboys from Nevada and Montana, however, knew him for his habit of drawing pictures of bucking horses and ranch scenes and pasting them to the walls of line shacks and bunkhouses.

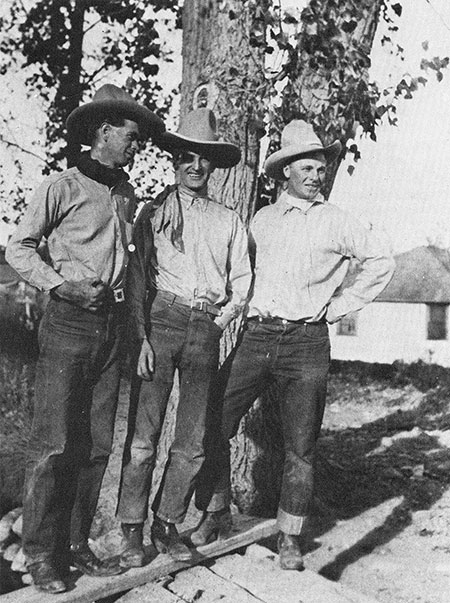

One reason for Will coming to Reno was to join his two buddies, Fred Conradt and Elmer Freel. This trio had worked often together, followed the rodeo circuit, chased wild horses, and whooped it up. They called themselves the “111s” (one-elevens). If you’re a fan of Will James, you have noticed a quick scratching of “111” on his early drawings beneath the signature. That was the brand of Reno’s “Three Mesquiteers.” It represented a pact that whoever one day owned a ranch would invite the other two to live and work there. Will James would be that ranch owner, and he kept his word.

Reno was a good base for the 111s since Fred’s family lived there and Elmer and Will always found a welcoming hand from Fred’s mother and sisters. The pleasure of home cooked meals with the Conradts was another incentive. Also, Fred was always sneaking in Will’s laundry for the Conradt sisters to wash. One sister, Alice, later married Will. None of the 111s had a job, and the slack season on the ranches dimmed any hopes for stock work.

Fred, however, had three broncs that he rented to rodeos. The boys decided to stage bucking horse shows in the local area and take up collections afterwards. It was a silly idea in many ways, but as Alice recalls, the 111s were a pretty silly bunch at times. The three broncs were named Hell-Morgan, Soleray, and Happy, the last so named because he looked anything but happy. The 111s talked over who was to get which horse. Will shied away from Hell-Morgan. That horse, used in the Reno rodeo a few weeks before, had done a fair job of tossing his riders, and Will had hinted to his partners that he was avoiding any more rough horses. So he selected Happy, while Fred drew Hell-Morgan and Elmer, Soleray.

Will and Elmer wanted to get the feel of their horses before trailing them to areas where they were likely to gather an audience. Along tagged Fred’s brother, Gus, to tak publicity poster. Fred ran the horses into the corral. Will roped Happy and started to throw on the saddle.

When Will described the event years later, he admitted that he should have known better than to use that saddle. Ready to stay off rough horses, he had purchased a roping saddle after his army discharge. It was a saddle hardly adequate for bronc riding.

“The boys,” said Will,”used to kid me about the cantle, saying all it was good for was to keep a feller from setting down.”

Actually it wasn’t the cantle that caused Will some second thoughts. It was a pair of 26-inch tapaderos that hung from the stirrups, along with a hunch that told him he should remove them. But the hunch wasn’t strong enough. Besides, Fred had said that Happy was only an average bucking horse and considered him easy pickings for Will. What they failed to consider was that Happy hadn’t been ridden for nearly three months and had a lot of time, as James later wrote, “to stack up on orneriness.”

While Fred eared Happy down, Will slipped into the saddle and settled himself firmly. He signaled his partner to let go of Happy’s ears. Immediately the horse leaped into a staccato of pile driving jolts. It was a hard series of bucks, but Will followed the rhythm and figured that Happy would be a breeze to ride.

Maybe Happy sensed Will’s overconfidence, for at that moment he shuffled to a stop and bowed his neck. Instead of making a hard, forward jump as Will expected, Happy went up and whirled in a backward spin. That black horse had thrown Will’s timing, and the saddle wasn’t any help either. In one of Happy’s spins, Will lost his left stirrup. He reached for the saddlehorn (since this wasn’t a public display he saw no need to take a fall unnecessarily) while his foot fished for the stirrup, but the tapadero was swinging the stirrup-like a kite.

Will knew he was putting on a bum ride, but he stuck to Happy as best he could. The horse floated from hard jolts to easy crow hops, and Will thought Happy was about ready to run. Heavy timber lay ahead, so Will decided it was a good time to hop off just in case Happy planned to clear the timber out of his way. Wiill braced and prepared to swing his right leg over the saddle and slide off. His left foot was still out of the stirrup. Then Will spied the railroad tracks flashing in the sunlight and decided to settle back until Happy had detoured away from them.

It happened mighty quick. When Will began to ease out of the saddle, Happy maneuvered out of his crow hopping and leaped into a succession of stiff-legged bucks—hard for a man who was halfway off his horse. The last jolt tossed Will into the air. He landed between the railroad tracks, and his head hit one of the rails. That was all he remembered.

A doctor spent 30 minutes patching the torn scalp and bandaging Will’s head while he was unconscious. When he awoke, Fred and Elmer helped him to stand. As they steadied him, Will began to sing, “Oh Bury Me Not On The Lone Prairie.”

There was a broad but sheepish grin on his face, and one of the spectators commented, “He’s out of his head.” Will looked at the man and answered, “You’d be out of your head too if you tried to bend a railroad track with it.” The 111s went back to riding after the accident since Will claimed he was all right. Years later, however, the injury would trouble him with severe headaches.

Happy was the last bucking horse Will ever rode. Happy had shuffled a new card to the top of Will’s deck. Next to horses, drawing was always something that had been part of him, and it was time to test his skills.

And that is what Will did, first to California where he sold vignettes of the cow country to “Sunset Magazine.” Less than a decade later he was an international name as the writer of the West. ‘T d like to see Happy again,” Will commented in one of his books. “And I’d like to touch his black hide in a sort of a handshake from one artist to another…So if I’m to be thanful, Happy is the one who’d get the first thanks.