Historic Sentence Fits the Crime

May – June 2017

The hanging of Elizabeth Potts marks Nevada’s only execution of a woman.

Photos courtesy of the Northeastern Nevada Museum.

Photos courtesy of the Northeastern Nevada Museum.“It is a dreadful thing to hang a woman, but not so dreadful as for a woman to be a murderer.”

BY BOB SAGAN

If “Dubious Achievement Awards” were handed out in 19th-century Nevada, Elizabeth Potts would have won by acclamation. Her husband would have shared in the honors, though he likely would have passed on the distinction if offered a choice.

It was June 20, 1890, in Elko, a mining and ranching town in the northeast corner of Nevada. Josiah and Elizabeth Potts were hanged simultaneously, side-by-side, for the murder of Miles Faucett, a neighbor and long-time acquaintance who, like the Potts, had migrated to America from Manchester, England.

It marked the first and only time a woman was legally executed in any fashion in the Silver State. Elizabeth was a housewife and mother of seven children. Children still living in the Potts household at the time included Charles, 16, and Edith, 4. Josiah Potts was a machinist for the Central Pacific Railroad, who had relocated from Milwaukee with his family.

The killing took place in Carlin, 23 miles west of Elko.

The killing took place in Carlin, 23 miles west of Elko.

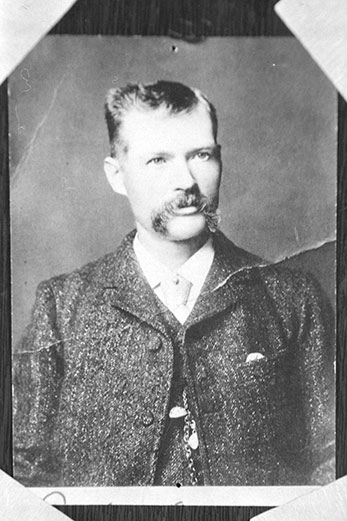

Elizabeth Potts

“Old Man Faucett,” as he was known in the community, was a miner and rancher and lived on a small spread outside Carlin. He frequently visited town and stayed with the Potts family, where Elizabeth washed his clothes and baked his bread for a fee. Elizabeth Potts was reportedly a forceful woman of some girth—an estimated 200 pounds at the time of her hanging. By contrast, Josiah was somewhat the milquetoast, physically smaller and timid, according to his neighbors.

The crime occurred sometime on Jan. 1, 1888, when Miles Faucett drove his rig into town and visited the Potts. At one point that day, Faucett was noticed hitching up his team outside the Potts residence. Then he went back inside the house and was never seen again. His sudden disappearance didn’t cause any great stir since Carlin was pretty much a transient town in those days. When Josiah was later asked about the 57-year-old Faucett, he claimed the old man had left for California and sold all his goods to Potts, for which Josiah possessed a bill of sale.

GHOST SPILLS THE BEANS … OR THE PICKLES

In September that year, the Potts family moved to Rock Springs, Wyoming, and shortly after, George and Amelia Brewer rented the Potts’ vacated house. Amelia had served as a correspondent for the Elko Free Press and considered herself a bit of a psychic. She sent the following to the Free Press on Jan. 5, 1889:

“I have intended to write you for several weeks, but when one moves to a new place one naturally is kept very busy for awhile…It is a little exciting when one has the good luck to move into a veritable haunted house. So far, the ghost hasn’t scared any of us, but he is here just the same. Sometimes he taps on the headboard of the bed, other times he stalks across the kitchen floor and then he hammers away at the door, but nobody’s there. But the gayest capers of all are cut up in the cellar.

There he holds high revels, upsets the pickles, and carries on generally.”

More incidents finally led George Brewer to investigate the cellar. After probing around with an iron rod, he found human remains. According to the official report, the head was “charred and fleshless, having been chopped up and burned. The legs, arms, and body were in small pieces and beyond recognition. The only clue to the body’s identity…was the half-burned pocket of the murdered man’s pants, in which was found an old knife…recognized as belonging to Miles Faucett.”

PICK UP THE POTTS

Suspicions were naturally focused on Josiah and Elizabeth Potts. A dispatch was sent to Wyoming, ordering the couple’s arrest. Carlin Sheriff L.R. Barnard and Constable J.F. Triplett went after them. On the way back to Nevada, the Potts claimed Faucett had killed himself after Elizabeth caught him abusing their daughter, Edith, and that Josiah had cut up Faucett’s body and burned it, fearing they would be charged with murder if it were discovered. No investigation of the abuse charges was ever reported in the court records.

When he heard the verdict, Josiah bowed his head and kept his eyes glued to the floor. Elizabeth’s demeanor never changed.The officers arrived in Carlin on Jan. 28, 1890, with their prisoners in tow and a hearing was scheduled before the local justice of the peace, resulting in the couple being bound over to the grand jury. On Feb. 13, husband and wife were indicted for murder. They pleaded not guilty and the case was set for March 12 before Judge John Bigelow. On that day, after arguments by the prosecution and the defense, Bigelow charged the jury. After four hours deliberation, the jury agreed upon a verdict: guilty as charged.

When he heard the verdict, Josiah bowed his head and kept his eyes glued to the floor. Elizabeth’s demeanor never changed.The officers arrived in Carlin on Jan. 28, 1890, with their prisoners in tow and a hearing was scheduled before the local justice of the peace, resulting in the couple being bound over to the grand jury. On Feb. 13, husband and wife were indicted for murder. They pleaded not guilty and the case was set for March 12 before Judge John Bigelow. On that day, after arguments by the prosecution and the defense, Bigelow charged the jury. After four hours deliberation, the jury agreed upon a verdict: guilty as charged.

“She looked straight ahead, as unconcerned as if she was merely a spectator instead of a leading character in a terrible drama,” the local newspaper reported. She did break down after returning to jail and shed a few tears, her jailer said, but soon appeared herself again.

The two were led into court for sentencing on March 22. Elizabeth appeared the coolest in the room. Josiah’s lips were quivering. Judge Bigelow consigned the couple to the custody of the sheriff until May 17, at which time they were to be taken out and “hanged until dead.” Not a muscle moved in Elizabeth’s face.

Their attorney appealed to the Supreme Court and a stay of execution was ordered. The Potts’ son, Charles, went to Oregon with a friend, but young Edith remained to visit her parents. Later, she would be adopted by a local couple, but not before she calmly told authorities she’d seen her mother shoot Miles Faucett while her father was away from the house. Whether a 4-year-old’s testimony played any part in the jury’s decision was never revealed.

After a short deliberation, the Supreme Court confirmed the lower court’s decision. When that decision came down, a petition was drawn up and signed by 267 Carlin locals asking the board of pardons to commute the sentence to life imprisonment. The commutation was refused, and Josiah and Elizabeth were re-sentenced to death—scheduled for June 20.

THE END IS NEAR

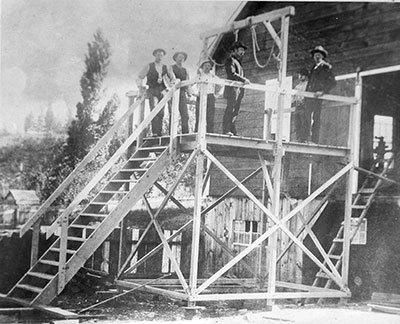

The gallows were erected and tested behind the Elko courthouse. At first, the condemned couple appeared strangely detached from what was going on until the beating of the carpenters’ hammers reached their ears. Both went through brief crying spells. Afterward, Josiah paced his cell while his wife cursed “the world and all in it.” She appeared the more stalwart of the two, but on the day before the execution, Elizabeth Potts slit her wrists with a small penknife she had hidden in her hair. When her attempt was thwarted, she “cut up fearfully” and then fainted.

June 20 dawned bright and clear. The death warrant was read to the couple and Josiah said simply, “We are innocent.” His wife raised her head and pronounced, “I am innocent, so help me God. We are innocent that’s all we can say from first to last.”

One of the jailers gave the couple a small bottle of “reinforcing tonic” (assumed to be whiskey) to help ease their anxieties. At 10:40 a.m., they were walked to the gallows. Husband and wife mounted the scaffold and took seats just behind a trap door big enough to accommodate both. Elizabeth was dressed in white with black silk bows at her throat and wrists. Josiah wore a business suit. Neither flinched as their arms and legs were strapped and their footwear removed.

ONE LAST KISS

They stood and the nooses were placed around their necks. They leaned into each other and kissed affectionately for the last time, and then black hoods were pulled over their heads. At 10:50, Sheriff Barnard sliced the cord that held the trap door spring.

The Potts were then taken side-by-side to a potter’s field and buried, ironically, near Miles Faucett’s remains. Josiah was 48, Elizabeth, 44.

In the aftermath of the Potts executions, the San Francisco Daily Report delivered a stinging rebuke to its city’s own courtroom climate when it opined:

“It is to the credit of Elko, Nevada, that it hangs a woman guilty of murder. It is a dreadful thing to hang a woman, but not so dreadful as for a woman to be a murderer. Evidently, Elko possesses citizens who, when on a jury, have some respect for their oath. In San Francisco, Mrs. Potts would have walked out of court a free woman.”

Many years later, Howard Hickson—at the time director emeritus of the Northeastern Nevada Museum in Elko—reported the following:

“Several years ago, I interviewed Charles Paul Keyser, then in his nineties. He was a teenager when he [shinnied up] a pole to watch the hanging. After he told me the story of the murder and trial, I asked him, ‘This couple was convicted pretty much on circumstantial evidence. Do you think they were guilty?’

“Agitated more than a nonagenarian should risk, he blurted, ‘Hell, yes! Everybody knew they did it!’”