Nevada Part II: From Strikes to Statehood

November – December 2013

BY RON SOODALTER

By the early 1850s, it had become apparent that the gold strikes recently made in the West were game-changing and would significantly impact the nation’s future. California, a recent prize in a war of acquisition with Mexico, had already established itself as a mecca for westward immigrants; the discovery of gold simply provided added incentive.

On the other hand, few were especially anxious to settle in what would one day become Nevada, at the time part of Utah Territory. Suddenly, a seemingly limitless cache of mineral riches focused global attention on this sparsely settled region and all but ensured Nevada’s remarkably rapid rise from a land that no settler seemed to want to its annexation as the nation’s 36th state, the Silver State.

ROUGHING IT IN THE GOLD & SILVER FIELDS

Although the initial strike was made in California in 1849, it wasn’t long before a number of frustrated ’49ers shifted their operations to neighboring Nevada. While most of the early settlers of Genoa (originally known as Mormon Station) applied themselves to making their mark—or at least their living—through business or farming, many Argonauts came looking for fast fortunes in gold and silver. Some chose to prospect around Genoa, while most made their way to the aptly named Gold Canyon, near Dayton.

Although the initial strike was made in California in 1849, it wasn’t long before a number of frustrated ’49ers shifted their operations to neighboring Nevada. While most of the early settlers of Genoa (originally known as Mormon Station) applied themselves to making their mark—or at least their living—through business or farming, many Argonauts came looking for fast fortunes in gold and silver. Some chose to prospect around Genoa, while most made their way to the aptly named Gold Canyon, near Dayton.

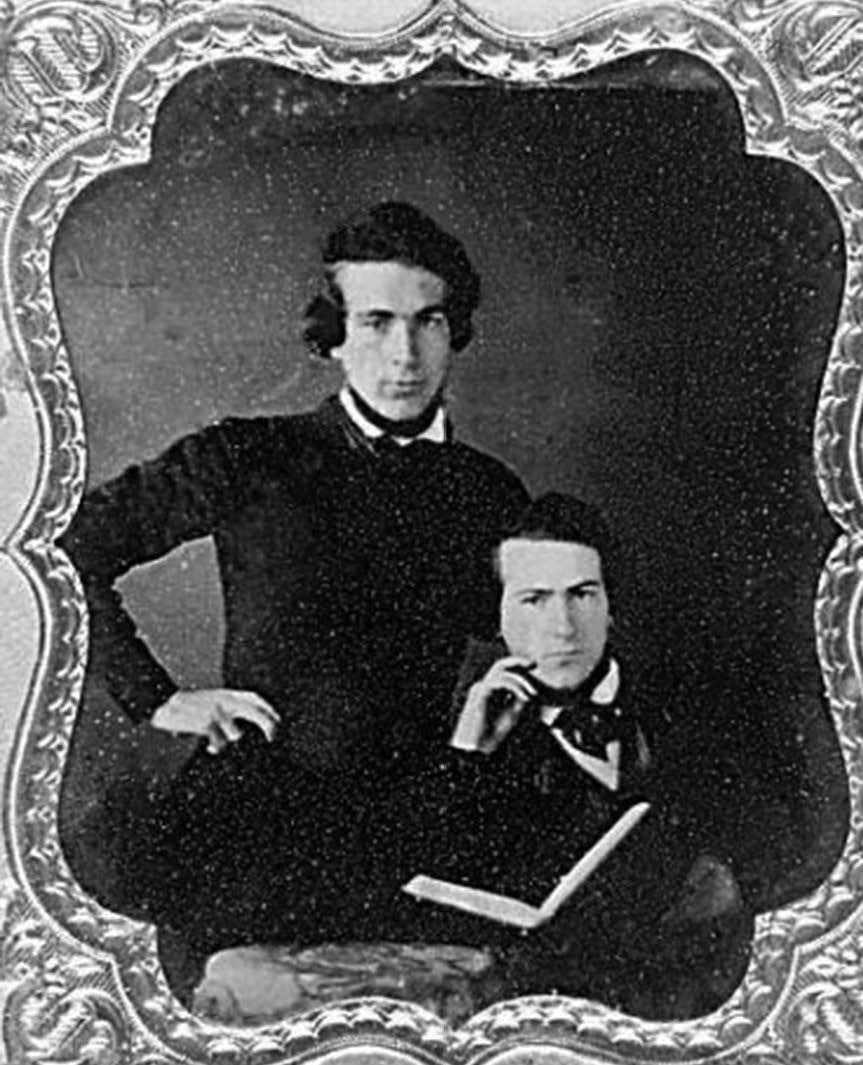

Typical of the exuberant hopefuls who sought wealth on both sides of the Sierra Nevada were Hosea B. and E. Allen Grosh, two young sons of a Pennsylvania minister. Their story is chronicled in the University of Nevada Press book, The Gold Rush Letters of E. Allen Grosh & Hosea B. Grosh. The Grosh brothers’ story demonstrates the hardships and tragedies that faced these fortune seekers.

The siblings left their family home in 1849 for the promise of riches across the continent in what only a year before had been part of a foreign country. There was no easy way to get there. Rather than risk a slow cross-continental journey by wagon, or a costly and perilous voyage around Cape Horn, the brothers—22 and 24—set sail for Tampico, Mexico in March 1849.

From there, they trekked overland toward Mexico City, securing passage to San Francisco. Illness—all too common among western emigrants—delayed their arrival in the California gold fields until summer 1850, by which time the “easy pickings” (if in fact such had ever existed) were long gone. Some prospectors still hunkered alongside likely looking creeks; however, placer mining was now the most effective system of operation, involving various processes of sluicing away the hillside dirt to expose the gold underneath. In a matter of months, the region had become dotted with placer mines, and the two brothers joined the hunt for riches.

From there, they trekked overland toward Mexico City, securing passage to San Francisco. Illness—all too common among western emigrants—delayed their arrival in the California gold fields until summer 1850, by which time the “easy pickings” (if in fact such had ever existed) were long gone. Some prospectors still hunkered alongside likely looking creeks; however, placer mining was now the most effective system of operation, involving various processes of sluicing away the hillside dirt to expose the gold underneath. In a matter of months, the region had become dotted with placer mines, and the two brothers joined the hunt for riches.

Although Allen and Hosea were constantly inventing devices to improve their odds—including an improved sluice box and what they referred to as a “perpetual-motion machine”—riches eluded them. More and more fortune seekers poured into the California gold fields, as less and poorer land became available, and the diggings yielded ever fewer results. There was no lack of physical afflictions in the camps, however, and the brothers suffered from dysentery, rheumatism, scurvy (with its resultant loss of teeth), and what one of them described as “cholera morbus, or something of the sort.”

Nonetheless, they persisted in the face of hardship and deprivation, acknowledging in a letter home, “For the past year we have made our own clothes, and…have bought two pairs of shoes! As to boots they were not to be thought of.” Finally, in July 1853, the Grosh Brothers decided to try their luck on the other side of the mountains, and—after writing their father, “We will start for Carson Valley tomorrow…. Ho! For the Mountains!”—they crossed the Sierra Nevada to Mormon Station.

After several weeks of fruitless effort, they moved their camp to the more promising vicinity of Gold Canyon.

Here in the Great Basin, there were considerably fewer miners at work, and the possibility of extracting precious metals was far greater than in the overcrowded, increasingly depleted hills of California. The new region was ideal for those who knew how to build and operate a placer mine, as the brothers wrote: “The miners here are about two or three years behind the age, so one acquainted with the machinery now used…in California has at least five chances to their one of making money.”

The brothers, however, elected to go a different route. Eschewing the washing of dirt that defined the placer process, they followed the advice of a local prospector to whom they referred to as “Old Frank” and set about hunting solid veins in the surrounding rocks. The ore they chose to focus on near Gold Canyon was not gold, but silver.

Hosea and Allen were, to a large extent, naive. There was considerably more to the mining of silver than chiseling it from the rock. Once discovered as veins, the processing of silver required an enormous outlay of manpower, capital, and technology. According to a centuries-old Mexican proverb, “It takes a gold mine to run a silver mine.” When silver finally did become the ore of choice during Nevada’s Comstock period, it was due in large part to the gold that existed in close proximity, as well as the financial ability of the owners to mine and process the silver.

As Virginia City author and journalist William Wright—writing in the 1800s with the pen name of “Dan DeQuille”—pointed out, “The discovery of silver undoubtedly deserves to rank in merit above the discovery of the gold mines of California, as it gives value to a much greater area of territory and furnishes employment to a much larger number of people.”

Nonetheless, the Grosh brothers spent nearly a year prospecting in the Great Basin before returning to California. They revisited Nevada twice more, in 1856 and 1857, still looking for the silver strike that would make them rich. Although they wrote their father that they had discovered “a perfect monster” of a vein, they never found their fortune. Some historians have posited that this “monster” ledge was, in fact, part of what would later become the Comstock Lode.

As for the Grosh Brothers, although their names have become inextricably linked with the early days of the Nevada strikes, neither was fated for a happy end. In August 1857, on their third sojourn into Gold Canyon, Hosea swung a pickax into his foot, inflicting a painful and serious injury; the wound festered, soon killing the younger brother. A grief-stricken Allen wrote his father, “God has seen fit in [H]is perfect wisdom and goodness to call Hosea, the patient, the good, the gentle to join his mother in another and a better world than this.”

The boys’ heartbroken father wrote back, “I have no words that will describe our grief and sorrow….There is something very painful in the idea of your remaining in Utah….arising from your utter loneliness there.” Worse news was yet to come.

Just weeks later, while attempting to re-cross the Sierra, Allen was caught in a blizzard and spent four days half-buried in snow with neither fire nor food. By the time he reached shelter, he had become badly frostbitten. Apparently, he had no idea of the severity of his condition. A light-headed Allen wrote home, assuring his father that he would survive, but feeling “very much ashamed at the confused note I have written you.” A postscript to the letter, written in pencil by a friend, states merely, “Allen died Dec. 19, 1857.”

NEVADA’S ’59ers

From 1850-59, between 100 and 180 miners worked claims in the Gold Canyon area, taking from their works some two-thirds of $1 million—an amount worth nearly $26 million in today’s currency. In the process, they discarded the dark sand that seemed to continually clog their rockers and slow the work. Only later would the “annoying blue stuff,” as they called it, prove to be a rich concentrate of silver, worth thousands of dollars per ton.

Then came the strikes that would impact the nation, create vast fortunes overnight, and forever change the history of Nevada. “What-ifs” are rarely useful in the study of history, but there is a possibility that, had the Grosh Brothers lived another two years, they would have played a significant part in the discovery of the massive gold and silver strike known as the Comstock Lode. In fact, after the brothers perished, their family hired an attorney in an unsuccessful attempt to secure a part of the discovery.

As it was, in January 1859, four men— including James Finney, known to the mining community as “Old Virginny”— found another section of “monster” ledge on nearby Gold Hill. Less than six months later, two other miners, Peter O’Riley and Patrick McLaughlin, followed this discovery with another—a silver- and gold-rich ledge of huge proportions—in Six Mile Canyon. The two discoveries heralded what would become one of the most profitable and productive periods in the history of American mining.

In the squabbles for ownership that followed these two extraordinary finds, one name continued to surface—that of Ontario-born former trapper Henry Thomas Paige Comstock. Variously described by contemporaries and historians alike as a lazy, “half-mad, loud-mouth trickster,” a “scoundrel,” and—worst of all—a “claim- jumper,” Comstock succeeded in pushing his claim to part-ownership in the discovery that ironically came to bear his name by “proving” that the spring on which the miners had been working belonged to him and his partner, Emanuel Penrod. The four agreed to share the claim. Ultimately, two other men were brought in specifically to crush the ore, and a six-way partnership was agreed upon.

At first, the discovery drew little notice, but when the ore from these and other local finds assayed at nearly $4,000 per ton, at a time when a value of $100 a ton was considered impressive, word spread rapidly. First reported in the July 1, 1859 edition of the Nevada Journal of Nevada City, California, by the following summer the diggings had triggered a response comparable to the 1849 Gold Rush. In fact, many of the miners and prospectors still struggling fruitlessly in California abruptly headed east across the Sierra.

The community that formed around the diggings was known as the Comstock Mining District. The concept of the mining district originated during the California rush and relied upon the formation of codes and selection of governing bodies from among the miners themselves, in the absence of formal local government.

The purpose of the mining district was laid out in the minutes of the Gold Hill Mining District: “[T]he isolated position we occupy, far from all legal tribunals, and cut off from those fountains of justice which every American should enjoy, renders it necessary that we organize in body politic for our mutual protection against the lawless, and for meting out justice between man and man….”

In extreme cases, “justice” as meted out by a miners’ court took the form of a short rope and a sudden drop, although surprisingly fair and equitable verdicts were more often the result. Thousands of hopeful prospectors poured into the region from all corners of the globe, and settlements swiftly sprang up near the various sites: Silver City, Gold Hill, and—reputedly named for “Old Virginny” Finney—Virginia City. The official establishment of Nevada as a territory in 1861 only added legitimacy to the rush of humanity and the overnight erection of boomtowns.

Meanwhile, the unscrupulous Henry Comstock, who managed to insinuate himself into the greatest find of the century, sold his interest for thousands of dollars—an impressive sum, but only a pittance compared to the millions his claim was actually worth and the hundreds of millions the lode would generate over the next two decades. He bought businesses, which failed, and married a Mormon wife, who left him shortly thereafter. In 1870, his money drained and nothing left to show but his name in the annals of Nevada his- tory, he took his own life.

The new communities boasted all the amenities one would expect to see in a thriving mining town. There were saloons and brothels of every description, some specifically suited to the ethnicity of their patrons. And it seemed there was always someone waiting to separate a miner from his “goods.” The same prospects of easy money that in later years lured gamblers to the Wild West boomtowns of Deadwood and Tombstone attracted cardsharps to the dens of Silver City and Virginia City in 1859.

For every miner who “struck pay-dirt” during the day, there was a gambler poised to take it away from him at night. And if he managed to hold onto his poke long enough to avoid the tables, a miner was easy prey for the dozens of “soiled doves” who practiced their trade in such saloons as Virginia City’s Old Washoe Club, or in the row of tiny “cribs” that stood along D Street’s “Sporting Row.”

The most famous of these ladies of the demimonde was Julia Bulette, who began plying her wares in Virginia City in 1863 and whose legend far outstrips the facts of her life. She has been variously described as willowy, wealthy, beautiful, and the “queen of Sporting Row.” Her earnings on any given night exceeded $1,000, payable in cash, jewels, or bullion.

According to former Nevada State Archivist Guy Rocha, she was none of the above, simply a popular prostitute who had the misfortune to be murdered. The local law apprehended, tried, and convicted James Millian of robbing and killing Bulette, and an estimated 4,000 spectators attended his hanging in 1868.

There was, however, more to the mining towns than their red-light districts. There were also stores of every description, elegant hotels, fine restaurants, schools, and—in Virginia City—an opera house and Nevada’s first newspaper, the Territorial Enterprise, which had relocated from Genoa. Courtesy of its bombastic writers, such as Dan DeQuille and Mark Twain, it boasted articles with such seductive headlines as “Dead Man Turns to Stone,” “Dead Indian Found in Water Tank,” and “A Gorgeous Scandal.”

INNOVATION ON THE COMSTOCK

Hard-rock mining had little to do with the earlier image of the lone prospector bent over a cold mountain stream, panning for “color.” The wealth of Gold Hill, Six Mile Canyon, and the other sites of the Comstock Lode was not simply lying about, to be scooped up and carried to the nearest assay office. Men had to go in, and down, after it.

As Allen and Hosea Grosh were among the first to realize, the gold and silver ore lay in veins in the rock, and beneath the ground, and had to be hacked out, crushed, and processed—all highly labor-intensive and costly steps. Would- be inventors that they were, the Grosh Brothers would have been impressed by the ingenious innovations devised for the extraction and processing of the precious metals that lay buried in the earth.

One of the first and most vital laborsaving systems was created in 1860, when Almarin Paul developed an ore-processing mill that became the standard among the miners. At the time of the Comstock discoveries, there were only two systems used for the extraction of silver—direct smelting and amalgamation through the use of mercury. Smelting, used only for the highest-grade ores, was costly; consequently, a cost-effective, predictable method of amalgamation was sought.

After much trial and error, Paul updated and applied a system that had been used in Mexico in the mid-1500s. It required crushing the silver ore to a fine slurry in stamp mills, mixing it with mercury, salt, copper sulfate, and water, and spreading out, re-crushing, and mixing the resulting “soup” in enclosed, steam-heated iron tanks known as pans. In a matter of hours, the silver could be separated from the mercury, although the exact effects of the various ingredients remain a mystery to this day. Paul’s “Washoe Pan Process,” as his system was known, was successfully used for decades.

German engineer Philipp Deidersheimer introduced an invention that saved countless miners’ lives in late 1860. He had been hired to improve the unreliable underground support system at the Ophir Mine. As the miners hammered and chipped ore from the cave walls, veins widened, the quartz that had previously held the ore became unstable, and the supports grew weaker and often collapsed. Cave-ins, costly in terms of both lives and profits, were not uncommon.

Deidersheimer devised a system in which pre-fabricated timbers, seven feet tall and four to six feet wide, and capable of supporting tremendous weight, were introduced into the mines. It was known as the “square-set timber method,” and— despite the additional cost of timber—it became the generally accepted system of support for the next half-century.

Other methods and tools were invented that had long-term, worldwide application. Elevator cages used for lowering miners thousands of feet into the ever-deepening shafts of the hard-rock mines were made possible with the development of the flat wire cable. Standard hemp rope proved too weak, and round wire cable tended to kink as it was wound. In 1864, a young transplanted Englishman named Andrew S. Hallidie solved the problem by simply flattening the wire, thereby keeping its strength, but making it easy to spool.

So successful was the method that San Francisco used it for its cable cars. Over the next several years, more and more innovations were applied to the extraction and processing of the precious metals, as well as to the improvement of the quality of life. One, the Comstock Water System, proved to be an extraordinary feat of engineering and earned global acclaim. Potable water—or, rather, the lack of it—had plagued the miners and settlers since their arrival in Carson County. The early settlers of Virginia City had relied on a system that pumped barely usable water from the mines. There was plenty of pure water in the Sierra, some 30 miles distant; the challenge was getting it down to and across Washoe Valley, up 1,500 feet to Virginia City, and another 500 feet to a likely reservoir site.

Hermann Schussler, another German civil engineer, having already demonstrated his uncanny ability in San Francisco, created a complicated but reliable water system for the burgeoning town. The Comstock’s location, however, presented the problem of scope. If successful, it would be twice the size of anything Schussler had built before.

Designing a complicated system of tunnels, flumes, and reservoirs, he built a pipeline that carried fresh water from the mountains, into the valley, and up to Virginia City. He created a type of inverted siphon that sent water uphill without the use of pumps. In all, he used some 700 tons of iron and more than 1,500 lead- sealed joints. So successful was the system that Schussler was hired to install versions of it in Tuscarora and Pioche. His work was solid; the dams and tunnels he built for the city of San Francisco in 1864 survived the devastating earthquake of 1906.

In mines the world over, the problems of flooding and poor ventilation have plagued the miners since time immemorial. In the mid-1860s, an enterprising businessman named Adolph Sutro established a company for the express purpose of draining and ventilating the mines. He proposed driving a three-mile-long tunnel from the Dayton vicinity to the Virginia City mines. So accurate were his calculations that when the tunnel finally met the Savage Mine, it was a mere 18 inches off target.

Unfortunately, it took so long to run his tests, obtain approvals on both project and budget (the cost reached a staggering $2 million), and complete the tunnel (nine years, finishing in late 1878), that the Comstock mines were waning just as Sutro’s tunnel became operational. Nonetheless, it was one more in a stunning parade of inventions that forever changed the face of mining.

In 1864, production at the Comstock flagged for the first time, causing many to abandon the mines for more promising prospects in central Nevada. It also provided the opportunity for the newly founded San Francisco-based Bank of California to establish a branch in Virginia City, loan money to the beleaguered local mine owners, and—when they were unable to pay back the bank due to the continuing depression—foreclose. In a short time, the “bank crowd” owned seven mills, as well as control of the leading mines. Soon, the Comstock would reveal new strikes, prompting a renewal of activity and making fortunes for owners and managers.

NEVADA BOOMS OUTSIDE THE COMSTOCK DISTRICT

The Comstock’s production slowed in the late 1860s, prompting some miners to leave Carson County to explore the possibilities in eastern Nevada, where a recent strike had produced silver assaying at $15,000 per ton—more than three times the value of the best Comstock ore. This find resulted in the establishment of White Pine County, with Hamilton named its seat. As quickly as the boom hit, however, it busted, just as the Comstock again showed strong signs of life.

And so it went: Miners would deplete the ore in one region, then move to another, and another, blanketing the Great Basin with brief but dramatic strikes. From Hamilton, they rushed northeast to Cherry Creek, and when the color faded there, back to the Comstock, wherein 1873—a truly phenomenal strike, the “Big Bonanza,” put the Lode on the map again.

This boom-and-bust mining pattern repeated itself throughout Nevada well into the late 19th century. New mineral districts at Unionville and Reese River developed outside the Comstock. Dozens of strikes, in such locations as Austin, Aurora, Belmont, Candelaria, Eureka, Pioche, and Tuscarora, dotted the landscape, attracting miners in numbers beyond the capacity of each strike to support. Each in its turn had its day, then petered out. Typical of the pattern was Aurora, which produced nearly $30 million in her first 10 years, earning a political status commensurate with her wealth. Predictably, the ore slowed, and along with her luster, Aurora eventually lost her position as county seat.

Despite the flash of new discoveries across Nevada, the Comstock remained by far the most productive. By 1880, the Comstock Lode had generated more than $300 million, out of a total territorial and state production of nearly half a billion dollars.

FROM TERRITORY TO STATEHOOD

Throughout the 1850s, as the region continued to produce large amounts of gold and silver, more and more of its citizens pushed for separation from Utah’s territorial government. Finally, over the strong objections of the Mormon administration in Salt Lake City, and after 10 years of effort and frustration, western Utah Territory achieved autonomy in 1861.

The delegates to the Nevada territorial legislature met three times—in 1861, 1863, and 1864. They strove to address a number of issues, the resolution of which would prepare the territory for its leap to statehood. Carson City, earlier named the seat of Carson County, would become the capital. The first legislature established and named a total of nine counties; by the time Nevada achieved statehood three years later, there would be 11. As for the name of the new territory and, hopefully, state-to-be, various options were examined, the first and erstwhile favorite being “Washoe.” Other likely choices were Humboldt, Esmeralda, and Nevada—the last of which was chosen by the delegates and announced in the November 7, 1863 issue of the Virginia Evening Bulletin.

The legislature eventually created some 28 toll roads to enhance the territorial budget and somewhat prematurely assigned several railroad franchises—none of which were used. The railroad was still in Nevada’s future. Interestingly, one of the first laws passed by the territorial legislature banned gambling. This law would remain in effect until 1869, at which time the legislature repealed it—over the governor’s veto.

The most vital task before the legislators, however, was the creation of a constitution, without which statehood would be unattainable. This proved to be a more difficult task than anyone had anticipated. While the residents voted strongly in favor of statehood in 1861, as late as 1863 the proposed constitution was overwhelmingly defeated by a vote of 8,851 to 2,157. The main reason generally given for the failure to adopt the constitution was an ongoing conflict regarding whether, how, and how much to tax the mines.

Enthusiasm for statehood was strong across the territory, however, and the 1863 defeat of the constitution did nothing to lessen it. By the following year, it was an aspiration shared by Congress and President Abraham Lincoln as well. In early 1864, both houses of Congress passed an Enabling Act for Nevada, setting certain conditions for its annexation. Among these were the drafting and acceptance of a constitution that was supportive of both the federal Constitution and the Declaration of Independence.

Another provision specified that Nevada would allow neither slavery nor involuntary servitude. By this time, the United States had been involved for three years in a Civil War that showed little sign of slacking. If the new constitution was accepted, Nevada would enter as a Union state in the strictest sense of the word.

Another provision specified that Nevada would allow neither slavery nor involuntary servitude. By this time, the United States had been involved for three years in a Civil War that showed little sign of slacking. If the new constitution was accepted, Nevada would enter as a Union state in the strictest sense of the word.

It was time for Nevada’s citizens—most of whom wanted badly to move up from what they perceived as “second-class citizenship”—to step up and approve a constitution.

James W. Nye, territorial governor appointed by Lincoln three years earlier, called for an election to select delegates to create a state convention that conformed to the terms of the Enabling Act. Initially, the process became an exercise in mudslinging, name-calling, and character defamation among the leaders of the pro- and anti-constitution factions. Old issues, earlier thought resolved, reared up again. At one point, even the choice of the name “Nevada” was belatedly called into question, and the former alternatives—Washoe, Humboldt, and Esmeralda—were brought up anew as possible substitutes. This issue was abruptly resolved when J. Neely Johnson, president of the constitutional convention and former governor of California, reminded the assemblage:

“Congress has provided that a State called the State of ‘Nevada’ shall be admitted after certain proceedings have been had, and the President is authorized to declare by proclamation the admission of the State of ‘Nevada’ into the Union…. Now the child is named; it had been baptized by the name of Nevada, and nothing short of an act of Congress can change that name.”

As before, the delegates debated taxes, railroad subsidies, and education. And most relevant to the current political situation, they argued over the subject of loyalty to the Union. After considerable effort, however, 30 of the 35 delegates signed the document, and on September 7, 1864 in an overwhelming display of support for statehood, the new constitution was ratified by a staggering vote of 10,375 to 1,284.

So anxious was Governor Nye to present the constitution to Washington in time for the November 7 presidential election that—rather than risk sending it by sea or overland mail—he elected to transmit it by telegraph. The resulting message took two days—October 26-27—to send and was the longest, most costly telegram ever transmitted up to that time. It consisted of 16,543 words, at a cost of $4,313.27 (around $60,000 today).

In an unusual gesture, Congress— which, according to tradition, approves state constitutions after their ratification by the people of a given territory—authorized President Lincoln himself to accept Nevada’s constitution, and to declare it a state, providing it met all the conditions of the Enabling Act. It did. On October 31, 1864, Lincoln proclaimed Nevada the 36th state in the Union.

By endorsing statehood for Nevada, Lincoln executed a political maneuver that is still debated among scholars and historians. Some chroniclers argue that he did this to avail the beleaguered Union of the fabulous riches flowing daily from western Nevada’s mining operations; this was not the case.

By endorsing statehood for Nevada, Lincoln executed a political maneuver that is still debated among scholars and historians. Some chroniclers argue that he did this to avail the beleaguered Union of the fabulous riches flowing daily from western Nevada’s mining operations; this was not the case.

Lincoln was a consummate politician, and he was facing a reelection campaign that he legitimately feared would result in his defeat. He needed as many votes as he could get, and by inviting Nevada—as well as the states of Colorado and Nebraska— into the Union as Republican states, he was ensuring a block of votes that would help put him across the finish line in first place.

Even more vital to Lincoln’s legacy than his reelection, however, was the need to pass the Thirteenth Amendment, which would finally and unalterably abolish the institution of slavery in the United States. By proposing the annexation of Nevada, Colorado, and Nebraska as slave-free states, Lincoln was hoping to provide enough support to ratify what would, in the end, become one of his greatest contributions to the growth of America as a free nation.

Nevada’s development in a few short years was nothing short of meteoric. No one living in the first few decades of the 19th century would have believed such a thing possible. During the days of the Spanish Empire, it represented a land to be crossed only when necessary. Then, when the trappers arrived, the so-called “Unknown Territory” briefly became a wild and often inhospitable source of furs, until they were depleted beyond profitability. For the emigrants heading west to Oregon or California, Nevada—and its vast Great Basin—merely presented a seriously challenging leg in a long and arduous journey to more promising climes.

But from the first discovery of precious metal in Carson Valley, and the establishment of Mormon Station and Dayton as the region’s first settlements in the mid- 1800s, to the unimaginable riches hewn from the Comstock rock in the 1850s, Nevada’s future was clear. In less than two decades, it had gone from a prospector’s seasonal camp to the Battle Born State.

COMING UP JANUARY/FEBRUARY 2014

Part III will address the “civilizing influences” on Nevada, during its pre-statehood and early-state- hood days. We will look at such icons as the Pony Express and Wells, Fargo in folklore, fact, and fiction; acquaint the reader with such bombastic pioneer newspaper men as Mark Twain and Dan DeQuille; introduce Jack Slade, the notorious pistoleer who wore his foe’s ears on his watch chain; describe the bloody Pyramid Lake War between Paiutes and settlers; and chronicle the dramatic establishment of Nevada’s railroads.

Read the Entire 8-Part Series

Part I: The Unknown Territory

Part II: From Strikes to Statehood

Part III: Twain, Trains, & The Pony Express

Part IV: Into the New Century

Part V: War, Whiskey, and Wild Times!

Part VI: Gambling, Gold and Government Projects

Part VII: To War and Beyond

Part VIII: Looking Forward, Looking Back