Yesterday: Steamers of Tahoe

November – December 2019

The first man-made craft to ply the crystalline waters of Lake Tahoe were the crude but efficient canoes of the Washoe Indians who lived on its shores. Trappers’ skiffs carrying furs and trade goods appeared in the mid-1840s and in 1856 the first sail-driven yacht was launched on the mountain lake. Two 28-foot whaleboats built in Sacramento and freighted over Johnson Pass by mule team were set to canvas in 1860 and a trickle of other small craft followed in later years.

These early craft carried freight and mail to isolated settlements on the fringes of the lake, but commercial exploitation of the large body of water did not really take hold until the discovery of vast mineral wealth on Nevada’s Comstock Lode in the early 1860s. The mines consumed vast hordes of lumber for shoring and the burgeoning towns of the Lode had an insatiable need for timber suitable for dwellings and business houses. Within two or three years the mountains around Virginia City had been virtually denuded of trees and timber was coming in from the Sierra to the west of Carson City. Small railroads into the mountains were constructed, as were V-flumes to move the large logs expediently down the rough gullies and canyons. As this source of lumber began to wane, new timbering areas began to open up on the west side of Lake Tahoe which led to the launching of the first steamships to tow lumber barges across the lake.

The steamers also hauled baled hay from the meadowlands to the west of the lake and freight-goods trucked up from Sacramento by jerk-line freighter or off-loaded from the Central Pacific at Truckee. Some steampowered craft also carried mail and offered passenger service of a sort on a catch-as-catch-can basis.

By the end of the 1860s, Tahoe was beginning to attract tourists and summer exiles from California’s teeming cities and humid valleys and several resorts and inns were put up to accommodate them. Enterprising steamer captains also saw some commercial possibilities in the increasing number of visitors and either fitted out their crafts in a more luxurious fashion or had new ones built.

Many was the vessel which featured a gleaming white pilothouse, a smooth, if not expansive dance floor, a well-stocked bar and a sun-shaded afterdeck. Some captains made arrangements for regular stage runs from Carson City and Sacramento while others engaged bands, vaudeville performers and singers for the entertainment of their guests.

Steam navigation was often a risky business, however, and boilers sometimes ruptured and sent the ships to the bottom. Lake Tahoe, although seemingly placid enough, can be unpredictably dangerous at times. There are hidden shoals and fierce storms sometimes blow over the Sierra and churn the waters into a raging torrent within minutes. Several captains lost their vessels during a cruise and there were many close calls, a number of passengers being saved from a watery grave only by the courageous and knowledgeable seamanship of the captains and their crews.

A number of vessels smashed themselves to bits against a pier when a storm hit in the middle of the night, but most were simply aqandoned when the expense of their upkeep exceeded the profits to be realized from keeping them in operation. Boilers, fire-boxes and fittings were scrapped and the lumber sold to build houses. Some were reconstructed into houseboats or anchored mooring platforms and at least one was purchased by the California Fish and Game Department to police commercial fishing on the lake which was allowed until 1917.

A number of vessels smashed themselves to bits against a pier when a storm hit in the middle of the night, but most were simply aqandoned when the expense of their upkeep exceeded the profits to be realized from keeping them in operation. Boilers, fire-boxes and fittings were scrapped and the lumber sold to build houses. Some were reconstructed into houseboats or anchored mooring platforms and at least one was purchased by the California Fish and Game Department to police commercial fishing on the lake which was allowed until 1917.

Two vessels, both built by Duane L. Bliss, outlasted all the others and did not see the end of their service until the late 1930s. The Meteor, launched in 1876, had an 80-foot iron hull and a beam of 10 feet. Constructed in Wilmington, Delaware, she was shipped west by rail in numbered sections and reassembled at Glenbrook. Journalists and those familiar with marine architecture swore that she would go straight to the bottom the moment she hit the water, but they were proved monumentally wrong. Not only did she float, but her single screw driven by a Baldwin locomotive boiler pushed her through the water at a clip exceeding 20 knots, which made her the fastest craft on any inland waterway in the U.S.

From 1876 to 1896the Meteor towed thousands of log booms across the lake and even under a heavy tow of 250,000 to 300,000 feet of sawed logs she could nold her own with steam vessels towing a third to a half of her freightage.

In the late 1890s the Bliss family got out of the lumber business, but the Meteor was refitted for passenger and mail service. Many very important and well-known people from throughout the nation accepted courtesy passes and lounged in comfort on the canopied decks as the trim craft moved effortlessly across the waters.

The Meteor changed hands in the 1920s when the Bliss family dissolved its transportation interests, but her usefulness was almost at an end because the first hard-surfaced roads into the basin in 1924 enabled automobiles and buses to take over both her mail and passenger service. She was hauled into drydock in 1928 and remained there until April of 1939 when William Bliss repurchased her and had her sunk rather than be sold as scrap to the Japanese government.

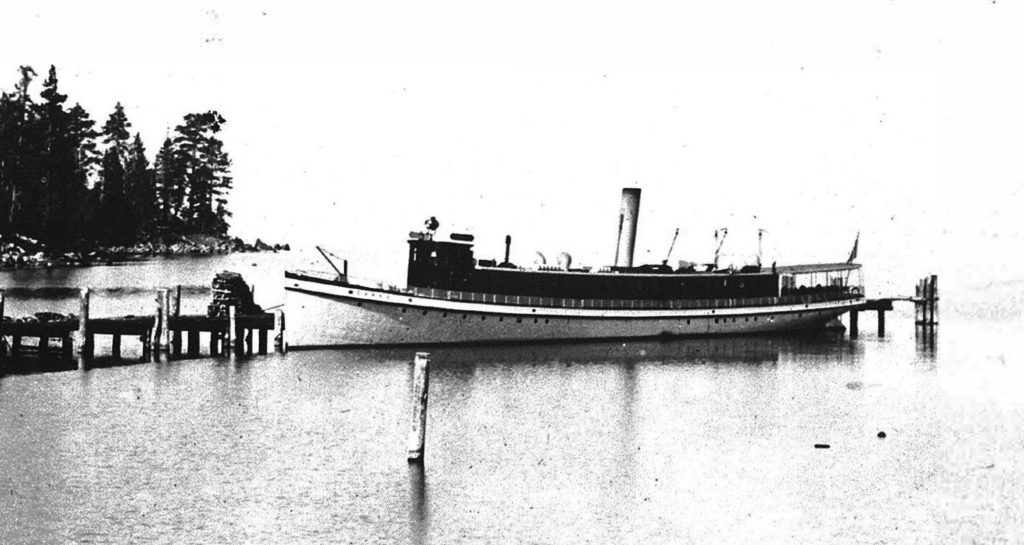

The second vessel owned and operated by the Bliss family was the Tahoe which was launched in June of 1896. Considerably larger than the Meteor, she could carry up to 200 passengers in elegant luxury. Teak and mahogany paneling, Brussels carpets, Morocco lounge chairs, and highly-polished brasswork set off the hundred-foot deckhouse while a gourmet dining room was located below deck. She also boasted hot and cold running water, white marble fixtures in her lavatories, a modern system of electric lights and a 4,000-candlepower electric spotligllt on the pilot house.

Over the years the Tahoe drove competing steamers out of the passenger and excursion business and private parties would come long distances to sail aboard her. She soon became part of the lore and legend of the lake and many old-timers have fond memories of calm, moonlit summer nights waltzing on her decks to the melodic strains of popular orchestras of the times. The Tahoe also played a part in several movies filmed at the lake, including “The Confession” made in 1917 and starring Henry B.Walthal. The glassy quality of the lake’s waters also made possible the filming of underwater pictures such as “The Navigator” which showed Buster Keaton standing on the bottom in a diving suit working on the propellers of the Tahoe.

The Bliss family also parted with the Tahoe in the 1920s, but she continued in operation until 1934 when her owners were underbid for the lucrative mail contract which had turned sufficient revenue to keep her going. For the next five years she lay dockside at Tahoe City, the paint peeling from her magnificent stack and rust eating into her sides as souvenir hunters stripped off anything they could carry.

No one knew quite what to do with her. There was some thought of making her into a floating night club, but her beam was considered too narrow for that purpose. Weekend cruises were also ruled out because of tlle expense of a full-time crew. Offers from the Japanese and other metal dealers were based only on the value of her weight in steel scrap and William Bliss finally bought her back in the spring of 1940 to save her from dismemberment.

Toward the end of the summer he decided that she should join the Meteor on the bottom of the lake and hired William F. Ham of Glenbrook to prepare her for sinking. Last-minute petitions from school children failed to save her, as did offers of money from Tahoe City residents who wished to turn her into a maritime museum.

Just at twilight on Aug. 29, 1940, she was towed from her moorings to a point several miles off Glenbrook. At 20 minutes before midnight, Ham boarded her and opened the sea valves. The tow vessel then resumed its funeral voyage across the lake, but within half an hour the towline began to tighten. The pilot backed water and the line was removed from the doomed craft. Her bow gradually began to lift and raised higher and higher until her anchor and chain were completely out of the water, swinging and clangoring against the steel hull. Shimmering in the glow of the tow craft’s spotlight, her bow suddenly knifed almost vertically into the blackness of the night and she hung there, transfixed, for long agonizing seconds before a rusted forward compartment ruptured and she slid quietly beneath the waters of the lake over which she had glided for nearly a half-century.

Boiling froth marked the spot where she went down and a muffled explosion was heard from the depths moments later. As the spotlight played on the water, the Tahoe’s flagstand rose into sight, its banner unfurled, clearly showing the craft’s name. A section of the pilot house floated to the surface moments later, as did a large piece of her superstructure which later drifted back to her old berth at Tahoe City, proof positive, if any was needed, that the Tahoe was more than just steel and wood. The flag floated into Glenbrook the next day and washed up on the shore near the point from which she had been launched many years before.

Those who loved the lake and the old steamer swore that her sinking was a sacrilege and it is said that on a clear day she can be seen on the bottom off Glenbrook. The story is also told that on occasion one can hear her bell tolling mournfully in the night and her deep-throated whistle blowing as it once did to announce her landings and departures.