Goldfield’s Historic Battle

November – December 2019

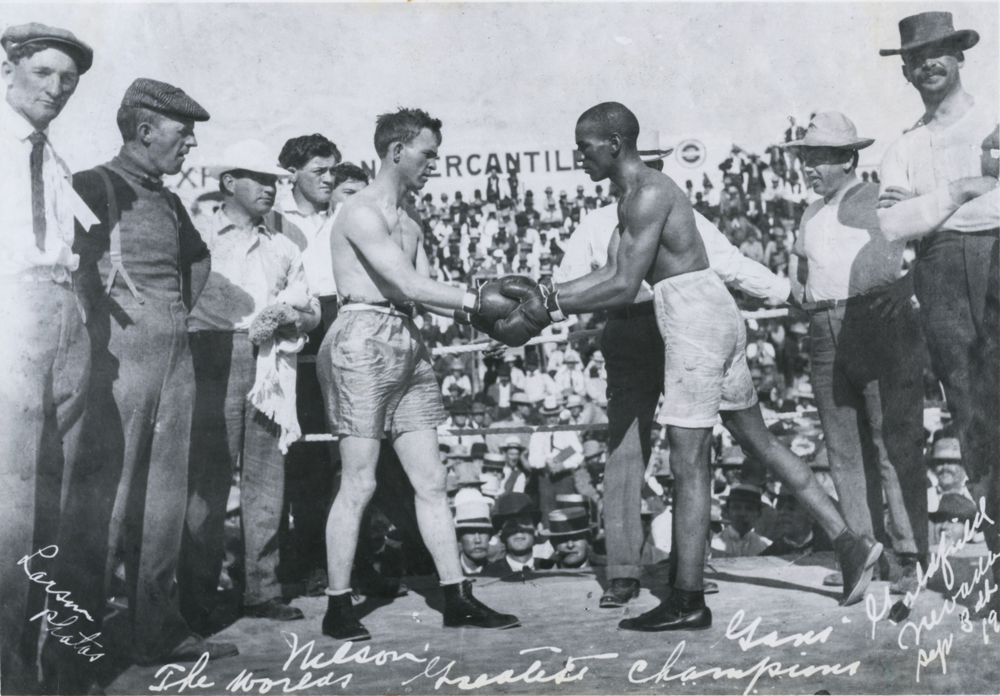

Gans-Nelson prize fight puts boxers and mining town on the map.

BY DAVID MCCORMICK

BY DAVID MCCORMICK

The thermometer was toying with the century mark on Sept. 3, 1906 in Goldfield, when two men touched gloves in the center of the ring. The fight was now underway. It was the favorite—Oscar “the Battling Dane” Nelson vs “the Rank Faker” Joe Gans, as the local press described him. Although Gans was the lightweight champion, Nelson was the favorite of the crowd amassed, as he was white, whereas Gans was black. Some newspapers of the day judged the crowd as numbering 15,000; in actuality it was a bit less than half that number at 6,072, but still enough to fill the hastily built open air arena. The purse was huge—some saying as much as $33,500—one third going to Gans and two thirds going to Nelson. The fight went to 42 rounds before it ended.

Although the crowd weighed heavily in favor of Nelson at the opening round, as the fight progressed, it became apparent the contest was no longer a white and black affair—skin color was no longer an issue. During the fight, the crowd seemingly moved in Gans’ favor. His superior boxing expertise seemed too much for Nelson. Although Nelson consistently carried the attack, it was Gans scoring most of the punches. Nelson was proving to endure devasting punishment; the pummeling he withstood from Gans’ fists would have put most men down. But at the end of the almost three-hour contest, Gans was declared the winner. Nelson, losing badly, purposely struck a low blow, dropping Gans to the mat; but his malevolent efforts didn’t pay off. He was disqualified for the low blow.

Although both men received beatings, it was Gans’ prizefighting technique that won over many in the crowd. “The Rank Faker” became “the Old Master.”

EAGER FOR NEWS

Those not attending the Goldfield fight were also hungry for news—they massed outside the offices of the “Reno Gazette-Journal” and the “Daily Nevada State Journal,” loudly responding to the round-by-round bulletins that were wired from ringside. The fight reports painted vivid accounts, “Nelson walloped his right hand to the jaw and followed with a left….” “Gans then peppered Nelson’s face with trip-hammered rights and lefts…until the gong rang.” When the round ended, Gans was far ahead of the bloodied Nelson. With each ascending round, one could almost see the action—the blood coming from Nelson’s nose and ears.

For 42 brutal rounds these two lightweights were locked in a monumental brawl. The fight, when finished, was one for the record books—it was the longest championship fight documented under Marquis of Queensberry boxing rules. Crowd members cheered rowdily when their fighter scored a number of blows, while others groaned when their favorite was on the receiving end. The crowd in the arena touted the match as the best ever seen—for a number of reasons. According to E.L. Houchin’s write-up in the “Daily Nevada State Journal,” what impressed people most was, “the cleanliness of Gans’ game, the Dane’s ability to stand punishment, and the financial success of the undertaking of the promoters who managed the contest…”

MORE THAN JUST A PRIZE FIGHT

The bout was promoted by “Tex” G.L. Rickard, owner of the Northern Saloon in Goldfield. Rickard was a native of Texas, who, by the time of the Gans-Nelson fight, considered Nevada his home. Rickard arrived early on in Goldfield when gold was first discovered there. When word of the proposed bout hit the dirt streets of Goldfield, many balked at the idea. Rickard, turning aside naysayers, went among the business and mining men, and within no time had acquired the purse of around $30,000 for the fight. By the conclusion of the famous fight, Rickard took in almost $70,000 in receipts for the bout. As of 1909, this was still the highest grossing American boxing gate that would not be surpassed until the Jefferies-Johnson fight that took place in Reno in 1910.

There was an ulterior motive in staging the bout in Goldfield—lure people into the community, thus, increasing the number of people willing to buy gold stocks. The official program highlighting the fight, proved this motive true. The headline “We know of a LISTED STOCK which will DOUBLE in price in the next 30 DAYS” was placed on the inside cover of the program and touted the business of Geo. F. von Polenz & Co. of Goldfield. Also listed within the program were the 60-plus members of the Goldfield Stock Exchange. At the time of the fight, Goldfield was a booming community with a population of between 15,000 and 20,000. Nevada itself was flourishing with more than 80 million dollars invested in Nevada stock in 1906.

LASTING LEGACY

During the bout, a camera was rolling, preserving the contest on film. This proved beneficial in peeling away myths about the bout. For instance, one story making the rounds was that of muleskinners with long bullwhips lashing at Gans’ legs. Another told of marbles being tossed into the ring by gamblers betting on Nelson to be the winner. In 2006, boxing memorabilia collector Gary Shultz insisted the film does not back up these farfetched stories. For a number of years after the fight, Gans-Nelson fight boxing enthusiasts still could not get enough of the marathon bout. They packed movie houses throughout the entire country to view the film.

The famous Gans-Nelson fight helped thrust the state of Nevada onto center stage as a milieu for the fistic sport and could not be outshined; it was a match for the ages. Although the pair met in two subsequent bouts—with Nelson winning both—neither of those later matches came close to the original 1906 fight that had taken the sporting world by storm. A year following the third Gans-Nelson fight, Gans was dead from tuberculosis. Gans wasn’t only fighting Nelson in those three bouts, but that cursed disease as well. Gans lacked the flash of some boxers like Muhammad Ali or Floyd Mayweather, but he held the title of lightweight champ from 1902 to 1908—making him America’s first black boxing champion.

On Sept. 16, 2006, a centennial celebration of the famous fight happened in Goldfield. Included in the celebration were six college bouts, pitting boxers from the University of Nevada, Reno against boxers from University of Nevada, Las Vegas. It’s fitting that the bell used ringside was the same one used in the 1906 Gans-Nelson bout.

The famous 1906 Gans-Nelson champion bout is forever intertwined with Goldfield’s rich mining history. The town’s boom days might be forever gone, but the battle between the two fighters is etched in Nevada’s sports history.