Nevada Part I: The Unknown Territory

September – October 2013

BY RON SOODALTER

The establishment of Nevada as a territory, and eventually a state, is a long and dramatic story.

It features every type of western character imaginable: Indians, Spanish friars, mountain men, explorers, surveyors, Santa Fe traders, prospectors, cowboys, railroaders, Mormons, desperadoes, and ladies of the demimonde.

For some, Nevada merely represented a vast expanse of inhospitable country to be crossed if necessary, or circumvented if possible, on the trek from the East to California. To others, it became a mecca of religious freedom, a gold-and-silver seeker’s nirvana, and a trapper’s paradise. Eventually, through boom, bust, and boom again, it found its way to statehood during the course of the Civil War and has since been aptly known as the “Battle Born State.”

ANCIENT HISTORY

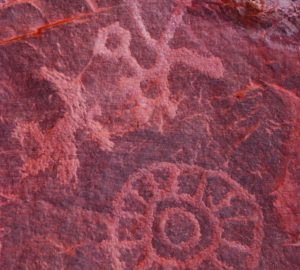

As was the case virtually everywhere throughout the centuries of settling North America, the Indians were here first. For millennia before the arrival of the Euro-Americans, paleolithic hunter/ fisher/gatherers ranged the vast reaches of what would one day become Nevada. No one can state with certainty just how long man has occupied the Great Basin, but modern-day archeologists have discovered grinding slabs, fashioned from flat rocks for the making of bread, dating nearly 10,000 years.

Eventually, tribal groups set up more stationary societies. The people of the Pueblo culture, which thrived within the last 1,000 to 1,500 years, left dwellings and artifacts as indicators of their lifestyle. The most famous such Nevada site is referred to as the “Lost City,” which some historians refer to as present-day Nevada’s “first center of population,” as well as its “first ghost town.”

Officially named Pueblo Grande de Nevada, it was discovered in 1924 and excavated over the next several years. It apparently housed a community of between 10,000 to 20,000 people whose lives incorporated farming, hunting, mining, and trading. As an archaeological discovery, it offered a brilliant and unparalleled window into the lives of some of Nevada’s early residents. A total of 121 “houses”—the largest containing a hundred rooms—were wholly or partially excavated, in part by Franklin Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps.

In 1938, however, Lake Mead resulted from the construction of Hoover Dam, and the Lost City was indeed forever lost. Miles of prehistoric sites now lie under several feet of water. Three years earlier, the National Park Service—anticipating the cultural loss the lake would cause—built a museum in Overton as a display and interpretation center. Operated today by the Nevada Division of Museums and History, the Lost City Museum features reconstructed Pueblo structures and offers school tours, art shows, outreach programs, and archival library and collections research availability on the peoples and geography of the area. By the time of the arrival of the first white men, the predominant tribes in what is now Nevada were the Shoshone, the Northern and Southern Paiute, and the Washoe, along with various bands and sub-tribes.

THE SPANISH EXPLORATIONS

The first Euro-Americans to encounter Indian residents in what would one day be Nevada were representatives of the Spanish Empire in North America. Lords of the region for some 300 years, the Spaniards approached the natives with the same ambivalence that characterized Spanish national policy elsewhere—with a cross in one hand and a sword in the other. Theirs was an occupation of brutality, incorporating subjugation and slavery with religious conversion.

In the late 18th century, the Spanish government envisioned a single connecting trail linking the two provinces of New Mexico and California, both to serve as a trade route and further solidify Spain’s holdings in the New World. In 1776, a Spanish priest, Father Francisco Garcés, set out to make the vision a reality.

Following an ancient Mojave trade route, he led a party from Sonora to the sleepy pueblo of Los Angeles and, in the process, became one of the first white men to cross the southern tip of presentday Nevada.

He and others, seeking religious converts as well as geographic connections, forged the first trail across the region. It was long and arduous and would be completed five decades later by a roughhewn group of American trappers, who used it in their quest for fur.

THE MOUNTAIN MEN

When Mexico won its independence in 1821, the British and Americans took it as an open invitation to seek valuable furs in the vast Western territory that had once belonged to Spain. Ironically, the rugged trappers, and the entrepreneurs who stood ready to buy their furs, were motivated by a single fashion accessory. Throughout the world, men were demanding and purchasing beaver hats, as a fashion statement and as a practical piece of headgear.

And nowhere was beaver more plentiful, or more profitable, than in the rivers, streams, and creeks of the American West. The venerable Hudson Bay Colony (HBC), known colloquially to its American competitors as “Here Before Christ,” sent trapping expeditions south out of the Pacific Northwest, while members of such St. Louis-based firms as the Rocky Mountain Fur Company traveled up the Missouri by flatboat, then westward by horse and mule to the uncharted mountains and plains. Beginning in the mid-1820s, a hardy breed of fur trappers who have become known to history and folklore as “mountain men” rode into the wilderness with little more than a knife and a single-shot rifle for protection.

The trappers ranged over great distances in search of pelts and, in the process, they charted heretofore-unexplored expanses of the West. Perhaps the most telling statement of purpose comes from the famous mountain man and explorer Jedediah Strong Smith, who wrote in his journal: “I wanted to be the first to view a country on which the eyes of a white man had never gazed and to follow the course of rivers that run through a new land.” The New York-born Smith was described by one chronicler as “the greatest of all mountain man explorers.” He was one of the few who could read and write, and he kept records and maps of his extensive travels. As a partner in the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, Smith blazed trails from the Pacific Northwest to Mexico, and from Utah to the West Coast, where he was arrested by the Mexican government for “military trespass.” Upon his release, he turned north and east, crossing and re-crossing present-day Nevada’s Great Basin.

Smith was the first to document the plants and animals of central and southern Nevada, as well as the lifestyles of its indigenous peoples. Smith’s luck ran out when he was only 32, when—while riding alone on the Cimarron in search of water for his party—he was attacked and killed by a band of Comanche Indians. But Smith left a legacy. His charts and maps laid the groundwork not only for future exploration, but for the settlers who would one day drive their wagons west at the oxpowered rate of six or seven miles a day.

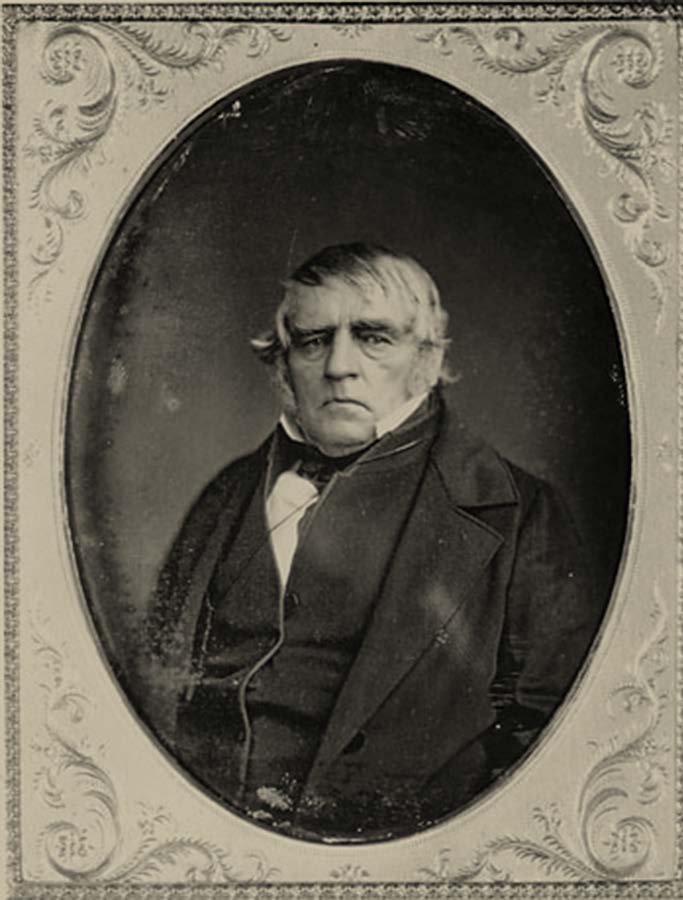

The American and British fur companies each approached the trade with the same goal in mind: to drive the other out of business. From the beginning, it was vital to reach the trapping ground ahead of the competition and, if necessary, to trap it to the point of extinction. For their part, the Hudson Bay Company could have done no better than to send out Peter Skene Ogden as their representative.

Born in Quebec and raised in Montreal by parents who had fled the American Revolution, Ogden was drawn early to the fur trade, clerking for various companies. He fled to the Columbia River country after killing an Indian, purportedly for working for the competition. He soon went to work for the North West Company, gaining notoriety for his violent actions against their competitor, the Hudson Bay Company. When HBC absorbed the North West Company, its governor, George Simpson, immediately fired Ogden, only to rehire him when he saw a use for his aggressive tendencies.

Traditionally, the lands below the Columbia River had been the domain of HBC, and Simpson feared an incursion by American trappers. He sent Ogden—whom he named chief trader for the company—on a series of expeditions to chart the expanse that now constitutes Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Oregon, and California, and, in the words of the Nevada Trappers Association, to “devastate the country as far as beaver supply was concerned.” He was to pursue this “scorched stream policy” to the point of “denuding the country and rendering it unprofitable…to Americans.” No less a prize than the entire Pacific Northwest was at stake.

Traditionally, the lands below the Columbia River had been the domain of HBC, and Simpson feared an incursion by American trappers. He sent Ogden—whom he named chief trader for the company—on a series of expeditions to chart the expanse that now constitutes Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Wyoming, Oregon, and California, and, in the words of the Nevada Trappers Association, to “devastate the country as far as beaver supply was concerned.” He was to pursue this “scorched stream policy” to the point of “denuding the country and rendering it unprofitable…to Americans.” No less a prize than the entire Pacific Northwest was at stake.

Ogden sallied out of his headquarters at Fort Nez Perces on the Columbia in 1826. He and his brigade are credited with being the first white trappers to enter Nevada. Although he only penetrated its northeast edge on this trip, he returned with a large brigade on three subsequent excursions—referred to as the “Snake Country Expeditions”—on which he not only discovered and explored the Humboldt River near present-day Winnemucca (while creating a route for future emigrants); he also trapped the Snake River and its tributaries, the Bruneau and Owyhee, in the area north of present-day Elko.

On his final excursion in 1828, Ogden led his brigade across the 42nd parallel, near what is now the tiny community of Denio—and he accomplished what he had set out to do. In the 11 months ending in July 1829, his brigade trapped some 4,000 beavers, thinning the population so severely that the Americans were forced to look elsewhere for their pelts. According to a recent Nevada Trappers Association study, The Fur Industry in Nevada, “From Peter Ogden’s reports through the gold rush days, numerous accounts documented the complete absence of beaver…in Nevada’s western river systems.”

A cursory glance at a list of Nevada place-names reveals a veritable “who’s who” of the old-time beaver men. In 1832, trapper, scout, brigade commander, and explorer Joseph R. Walker led a party around the Great Salt Lake in search of an overland route to California and, while doing so, followed the Humboldt River west. Today, a Nevada river, lake, and pass bear his name.

The redoubtable Christopher “Kit” Carson ran away from indentured servitude in Missouri as a teenager, became a mountain man, and grew to be the most famous of the breed. He became a sought-after guide and was famed explorer John C. Fremont’s scout of record. It was on one of their explorations that Fremont named a river for his invaluable guide, and when a small community sprang up near its banks, the settlers gave it his name as well. Eventually, the settlement of course became Nevada’s state capital.

Despite the attention given to it in novels and movies, the fur trade lasted a remarkably short time. Although small expeditions were staged as late as 1844, by the early 1840s it had all but died out.

There were two reasons for the trade’s demise. The seemingly endless supply of beaver had been over-trapped nearly to extinction—first in the rivers and creeks of the plains, then in the mountains. And the popularity of hats made of silk usurped those made of beaver.

Of the trappers who survived in the wilderness, some went back to civilization, while others remained in the West, serving as scouts and guides and offering their invaluable knowledge of the country to the Army, the wagon trains of westering settlers, and the various corps of exploration that followed. Men like Carson, Walker, Jim Bridger, and John “Liver-Eating” Johnson provided an invaluable service to those looking to cross, explore, and exploit the West. In a very short time, the territory that would one day become Nevada saw its share of exploration—and exploitation.

By 1829, Nevada was being generally referred to as the “Unknown Territory,” and trappers were not the only white men to feel their way through it. Beginning in that year, various New Mexico-based traders, motivated by the hope of finding negotiable trade routes to California, also ventured into and across its southeastern tip. Among the first was an enterprising New Mexican trader named Antonio Armijo. Armijo led nearly 60 men from Abiquiu across Southern Nevada, through the Las Vegas Valley, and along the Amargosa River to Los Angeles. They followed the route taken long ago by the Mojave and followed by the Spanish padres decades earlier. Over time, it came to be known as the Old Spanish Trail.

No single Indian, trapper, trader, or explorer “discovered” it. As historian LeRoy Hafen describes, “This was a folk trail, mastered segment by segment through many years and many forces….” It became the earliest trail to course across a section of Nevada—and it was far from ideal. Although it served briefly as a means of delivering fine woolen blankets via caravan from New Mexico to California, the 1,200-mile trail was, in Hafen’s words, “the longest, crookedest, most arduous pack mule route in the history of America.”

For the westward-bound emigrants who would come later, the Old Spanish Trail was an untenable route. Because it meandered over wild rivers, “mountain passes, precipitous canyons…sandy arroyos, granite ranges, broken plateaus, and waterless mesas,” through “an unmapped land of untamed Indians,” it was fit only for pack mules and horses. Taking wagons across it was out of the question. More serviceable trails would soon follow, as other white men entered the Great Basin for reasons other than collecting furs.

THE MAP AND CHART MEN

The second “exploratory phase,” which took the form of government-sponsored expeditions, burgeoned in the early to mid-1840s. It was a period during which the American eagle was spreading its wings and laying claim—through war or negotiation—to all lands east of the Pacific Ocean. It was one of the largest land grabs in modern history, and those who justified it as the nation’s God-given right of expansion referred to it as Manifest Destiny. The vast territory acquired through the Louisiana Purchase had long since been explored, and—armed with an unshakable belief in its superiority—America looked to the Far West to fulfill its birthright.

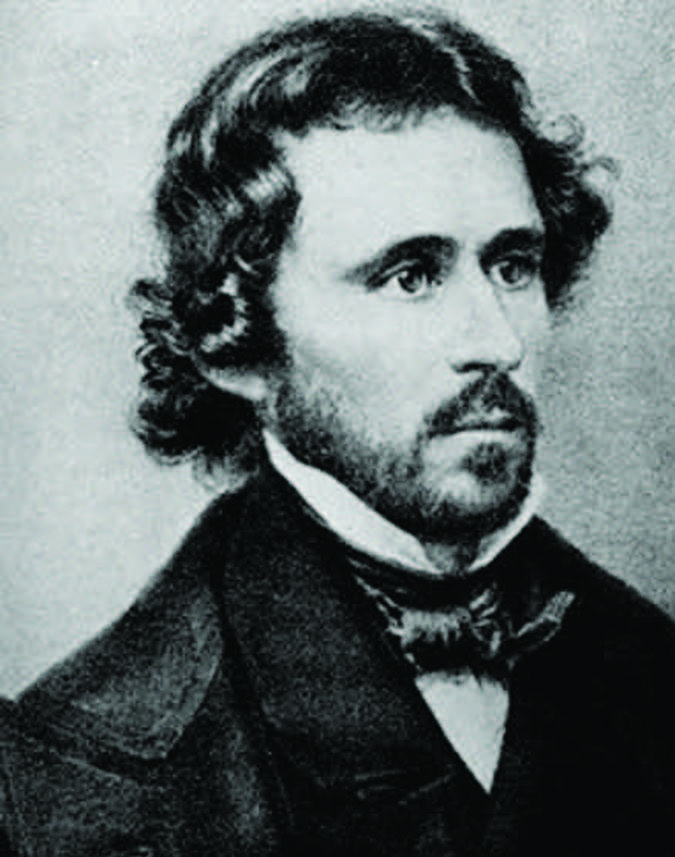

It began with the 1845 annexation of Texas and continued through the Mexican War, which netted the United States the lands that had formerly comprised northern Mexico—lands that would ultimately break down into the states of New Mexico, Utah, Arizona, California…and Nevada. In 1842, in anticipation of acquiring this vast expanse, the U.S. Topographical Engineers sent an enterprising, dashing young adventurer on the first of what would be three extensive surveying expeditions into the West. His name was John C. Fremont, and he was the son-in-law of one of America’s most vocal advocates of expansionism: Senator Thomas Hart Benton.

It was Fremont’s second and third surveying and trailblazing expeditions, in 1843-44 and 1845, that would earn him the sobriquet, “The Pathfinder.” He not only scientifically mapped and described the “Unknown Territory” in detail, he charted the trappers’ and Indian trails that crossed it. In December 1843, Fremont “discovered” and gave Pyramid Lake its American name. He also followed the Truckee River (which he coined the Salmon Trout River after its red-hued cutthroat trout) and the Carson River and—on his trek across the Sierra Nevada—was the first American to report sighting Lake Tahoe. He re-entered Nevada and followed a stretch of the Old Spanish Trail through Las Vegas and Moapa Valleys, and along the Virgin River. So successful was he in his explorations that Congress printed 20,000 copies of his route map—an unheard-of quantity for its time.

During the course of his 1845 expedition into Nevada, Fremont studied and remapped in detail the basins of the Carson, Truckee, Walker, and Humboldt Rivers and—with his newfound knowledge of the area’s interior drainage—named the Great Basin. He was not the first white man to view the natural wonders that he charted. However, taking a page from the travels and hard-won discoveries of the mountain men, Fremont had collated and formalized the charting of Nevada.

WESTWARD BY WAGON…

Fortuitously for the young nation, the U.S. victory over Mexico in 1848 coincided with the discovery of gold in California. Suddenly, the prospect of defining viable transportation routes to the West became a pressing necessity. In the early 1850s, the federal government raised money and sponsored additional “corps of discovery” to define and chart overland trails suitable for wagon travel.

The idea of westward migration was not a new one. The earliest group to set its sights on California—the Bidwell- Bartleson Party—left Missouri in 1841. They became the first emigrant party to cross the Great Basin. According to Nevada historian Russell R. Elliott, their “inexperience was exceeded only by their foolhardiness.”

Led by John Bidwell, a starry-eyed young schoolteacher who had absorbed the newspaper tales of the mountain men and large California landowners, the small party set out across the wilderness with neither guide nor clear picture of what lay ahead. Fortunately, they ran across famed mountain man Thomas “Broken Hand” Fitzpatrick, a former partner in the Rocky Mountain Fur Company who guided them as far as Soda Springs in present-day Idaho.

From there, Bidwell and his party made their way south to the Great Salt Lake and west across the salt flats. They struggled across the Ruby Mountains, and along the Humboldt to its sink, then crossed the forbidding Sierra Nevada, arriving in California’s San Joaquin Valley in early November. For Bidwell, the exhausting trek proved a godsend. He made a gold strike soon after the initial discovery at Sutter’s Mill, rising to wealth and prominence in the new land. Pioneer, farmer, soldier, statesman, and politician, Bidwell even ran for president of the United States in 1892—on the Prohibition ticket.

Other parties made their way west across the Great Basin in the early 1840s, each going a step further in forging what became the California Trail. The most significant was Elisha Stevens’ party, which rolled west out of Missouri in May 1844. When they reached the Humboldt Sink, Stevens’ party met a friendly Paiute chief who showed them an accessible wagon route over the Sierra, by means of the river and pass that now bear what might or might not have been his name: Truckee. Although there were many trails—and many cutoffs—leading west, this latest iteration of the California Trail became one the most accepted routes for future emigrants.

After the discovery of gold in 1849, traffic on the trails across Nevada increased a thousand fold. There were, however, those for whom the trail—however proven— seemed too long and who sought other, shorter means of reaching California or Oregon. Sometimes, disaster followed. In 1848, a Danish Immigrant and California rancher named Peter Lassen put out the word via eastern newspapers that he had found a shortcut that would get prospectors to the gold fields faster. In fact, he designed his dubious route to pass by his ranch, where he hoped to exploit the weary travelers.

Instead of a shorter route to the west, the detour by which Lassen led thousands of credulous victims ran north, from the dry end of the Humboldt River in Northern Nevada, through the Black Rock Desert, and across waterless mountains. It was far longer—and more brutal—than the main trail. He called it Lassen’s Cutoff; travelers soon labeled it the “Death Route.” In train after unsuspecting train, animals perished in droves, wagon wheels dried up, shrank, and fell apart, and people suffered and died.

At one point they reached a spring, which one traveler called “an abomination of desolation…ash heaps into which slowly percolated filthy looking brackish water.” Another, likening the flat, sun-blasted terrain to an oven, wrote, “The rocks resemble cinders about a furnace.” One emigrant was awed by the sheer numbers of dead creatures: “I do not think I have been out of sight of a dead carcass, and in many places the road is blockaded up so you are compelled to leave it or pass over their dead bodies.”

One survivor of Lassen’s Cutoff wrote in a letter home: “Dear George: There was some talk between us of your coming to this country. For God’s sake think not of it. Tell all whom you know that thousands have laid and will lay their bones along the routes to and in this country…and as for you, STAY AT HOME…”

A strange justice overtook Lassen in 1859 in a canyon near the Black Rock Desert. He was traveling with two companions on his way to prospect for silver near Virginia City, when an unknown party shot and killed him. Thus, the “most hated man in California” met his end. Locals blamed hostile Indians; others who had taken the infamous Lassen Cutoff assumed it was one of his victims, exacting revenge.

The most famous “cutoff disaster” is that of the Donner Party. In 1846, after departing late in the season, some 87 emigrants found themselves trapped by snow in the Sierra Nevada. They had taken a cutoff endorsed by Lansford Hastings, a jingoistic 1840s writer whose driving ambition was to see California taken from Mexico and declared a republic, with himself perched on the political top rung. To lure Americans to the West Coast, he had penned The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California. In it, he advocated a cutoff—which he himself had never taken.

The route, which the Donner Party elected to follow, took them across the Wasatch Range and the salt flats, piling on hardships and seriously delaying their progress. By November they were snowed in and, by the time a rescue party reached them in February, only 47 had survived, having resorted to cannibalism.

The tragedy technically occurred in California, and the town of Truckee boasts Donner Memorial State Park, which includes the Emigrant Trail Museum. Its displays describe the saga of the thousands of emigrants who traveled the route to California, as well as details of the Donner Party ordeal.

…AND BY RAIL

Not only was the federal government concerned with finding passable wagon trails for thousands of western emigrants, it was also looking to select and survey potential routes for a transcontinental railroad. This proved a harder task than anyone had imagined.

The first railroad survey to incorporate Nevada in its plan was led by Lt. Edward F. Beale in 1853, and it included a segment of the Old Spanish Trail. That same year, Fremont made his fourth and final excursion in an unsuccessful search for a suitable railroad route. In the process, Fremont led his party into Nevada at what is now Pioche, through the White River Valley, and past the site of the Tonopah Test Range and Stonewall Mountain, exiting near present-day Beatty.

Beale was followed the next year by another army officer—Lt. Edward G. Beckwith—who entered Nevada with orders to explore the Great Basin in search of “the most practicable route to the valley of the Sacramento River.” Over the next five years, there would be other army officers leading other railroad expeditions. Captain James H. Simpson headed the most thorough in spring 1859. His 65-man company of specialists from the Corps of Topographic Engineers entered Nevada through Pleasant Valley and proceeded to gather information on the region’s Indians and geography, as well as create the most comprehensive map of Nevada up to that time.

When the various surveying expeditions had completed their work, Secretary of War Jefferson Davis (soon destined to serve as president of the Confederate States of America) selected four possible paths for the “Iron Horse”—none of which was ultimately adopted. The Central Pacific would not begin to lay track in Nevada until 1868, four years after Nevada achieved statehood.

THE FIRST SETTLERS–Genoa

Although most of the thousands of emigrants bound for California were simply passing through Nevada as they followed the lure of gold, there were some who either stopped in or returned to Nevada to seek their fortunes. It didn’t take long for enterprising men of commerce to realize that the goods, tools, and supplies of the westering pioneers would run down or simply wear out over the hundreds of miles of hard use. The nearer the journey’s end, the greater the need would be for refitting. Consequently, a number of supply depots and trading posts appeared along the trail.

The first supply station intended for permanence was built in the scenic Carson Valley in 1850 by a group of Mormons under the leadership of Captain Joseph DeMont of Salt Lake City, at the site of present-day Genoa. DeMont and company had originally intended to mine for gold in California but realized that a more certain road to riches lay in taking commercial advantage of others headed to the gold fields.

They built a trading post—which at first was nothing more than a small, canvasroofed log structure—in a strategic location along the recently blazed Emigrant Road, named their endeavor “Mormon Station,” and stocked it with goods from Sacramento. Many thousands of emigrants passed through Carson Valley in 1850 alone, and the cabin was cannily placed to provide them with much-needed supplies.

With winter approaching, DeMont, his clerk Hampton S. Beatie, and the other investors—facing the unpleasant prospect of isolation—reportedly sold out to a Mr. Moore and went their separate ways. Early the next year, Salt Lake City residents and brothers John and Enoch Reese, envisioning a permanent settlement at the site, bought the old DeMont trading post from Moore. John loaded several wagons with goods for sale and seeds for planting and proceeded to Mormon Station.

His first order of business was to abandon the original roughhewn log cabin and put up a solid building with a stockade—thereby erecting the first permanent structure in Nevada in 1851. The emigrant wagons and carts came through in a steady flow, and the valley’s grass and soil were ideal for grazing and planting. Within the year, Reese was prospering, and—as he had envisioned—his little community began to grow.

Technically, with the recent passage of the Compromise of 1850, most of Nevada had been made a part of Utah Territory. This placed all residents of Carson Valley—traders, miners, and settlers—under the aegis of the territorial government based in Salt Lake City, where Brigham Young served as governor. Still, rather than wait for a distant and inattentive administration to notice them and address their increasing list of needs, some 100 residents held “squatter” meetings and basically drew up their own constitution, containing a set of laws to protect the property and wellbeing of the community.

Eventually, the territorial government would re-establish control over the settlement, which constituted its westernmost—and farthest—colony, but for now, they were on their own. Mormon Station prospered. In July, the Sacramento Union reported that it consisted of “3-4 buildings, a tent, a spring house, and 2-3 corrals.” By the next year, in addition to several residences, it also boasted two blacksmith shops, a number of stock corrals, orchards, fields of hay, rich gardens and crops of fruit and vegetables, a bakery, a post office, and—at the southern end of the valley—the first sawmill in Utah Territory. Soon, fences went up, claims were filed, and the settlement took on an air of permanence.

Finally, in 1854, Young got around to setting up a government for western Utah Territory, which included Mormon Station. Early the following year, he sent church official Orson Hyde to the valley to establish Carson County and represent the territorial government as probate judge. Arriving with 38 Mormon settlers, he immediately built another sawmill and changed the town’s name to Genoa—reportedly after the birthplace of Christopher Columbus, whom he was said to admire.

Harsh feelings soon arose between the gentiles and the Mormons, whose numbers allowed them to occupy most of the elective offices. Non-Mormon residents went so far as to petition—unsuccessfully—to become part of California. Nonetheless, despite the internal friction, the town thrived. By 1857, Genoa consisted of 25 buildings, including a billiard hall and at least one hotel, and was bordered by farms and ranches.

That same year, President James Buchanan ordered a contingent of American military forces into Utah, and Young—fearing the worst—called hundreds of Mormons back to Salt Lake City to mount a defense. Judge Hyde himself had returned the previous year, and—with most of its abdicating officials back in Salt Lake, Genoa’s Mormon-run local government collapsed. For the next two years, order was maintained in Genoa by vigilantes until superseded in 1859 by federally appointed officials.

Dayton

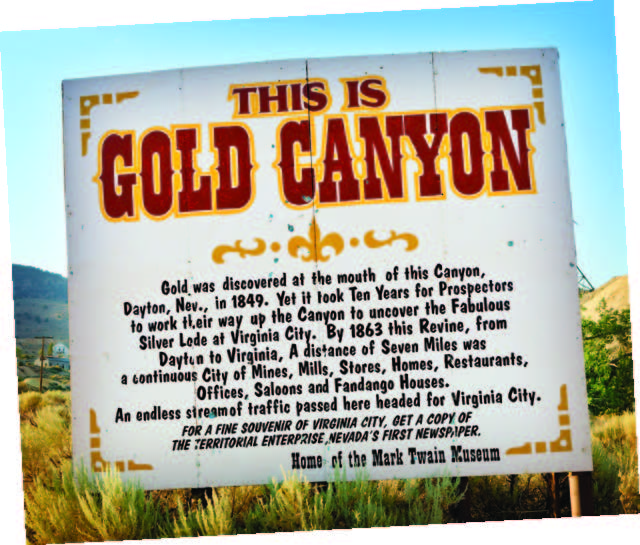

Meanwhile, as more and more get-richquick 49ers were walking, rolling, or riding to California, a few errant prospectors discovered gold in a canyon near the site of present-day Dayton. Although the pickings were small at first, the location came to be known as “Gold Canyon,” and it succeeded in stopping the westward progress of several “Argonauts” and in bringing others back from the California diggings.

Some enterprising prospectors set up camp in Gold Canyon in the warmer months, then trekked across the Sierra Nevada to California during the winter. Gold Canyon became a veritable melting pot of ethnic diversity, with Chinese, Mexican, and Indian prospectors joining the Anglos in their frantic search for the precious metal. James Finney, a prospector and local character better known as “Old Virginny,” spent the winter of 1850-51 in Gold Canyon, apparently earning the distinction of being the first Euro-American to winter in Utah Territory.

By summer, some 200 prospectors had elected to seek their fortune in the canyon, although—according to Nevada historian Terri McBride—”the settlement…still had a transient, temporary air since no permanent buildings were erected.” A log trading post consisting of three cabins went up the following year, along with a boardinghouse and tavern and a rail system for hauling ore from the canyon to the river.

Gold Canyon, as its name implies, was mined for its precious minerals, while Genoa—initially established as a trading post—grew more as a commercial and farming community. To this day, there is disagreement over which settlement—Genoa or Dayton—was the first to sink its roots in what would soon become the State of Nevada.

Other settlements began to pop up in the 1850s. Some, such as Ragtown, were simply way stations, thrown up along the trails to California, while others—Virginia City and Carson City—grew to permanence, earning their place as linchpins in the growth and development of Nevada. The 1850s were promising for the territory’s future—one that included wealth far beyond the imaginings of even the most ambitious prospector or investor.

Read the Entire 8-Part Series

Part I: The Unknown Territory

Part II: From Strikes to Statehood

Part III: Twain, Trains, & The Pony Express

Part IV: Into the New Century

Part V: War, Whiskey, and Wild Times!

Part VI: Gambling, Gold and Government Projects

Part VII: To War and Beyond

Part VIII: Looking Forward, Looking Back