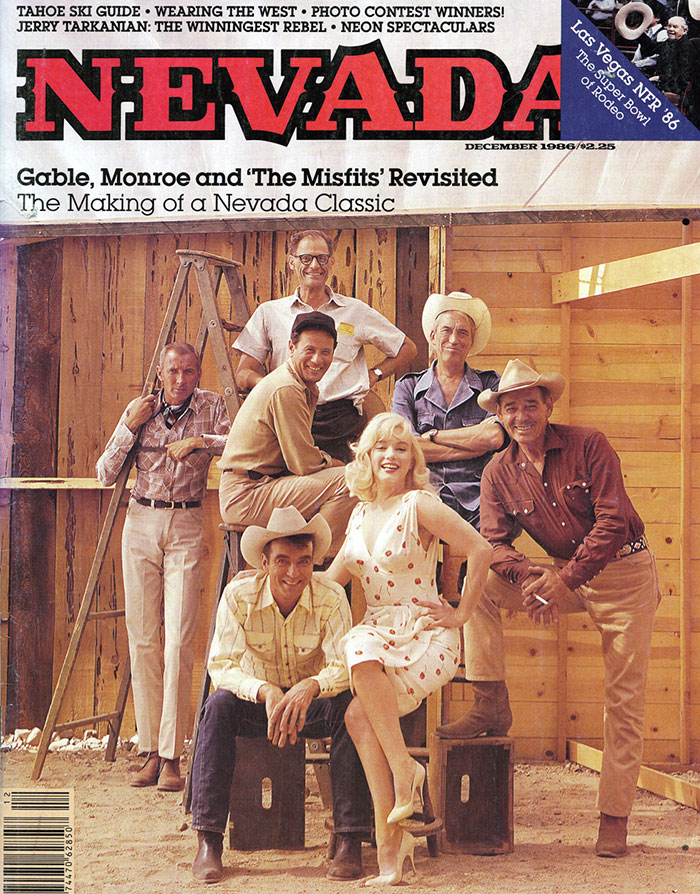

Yesterday: The Making of ‘The Misfits’

Spring 2021

When John Huston, Clark Gable, and Marilyn Monroe came to Reno to make a movie ‘about a world in change,’ the whole town got into the act.

BY JOHN GOODE

This story originally appeared in the November/December 1986 issue of Nevada Magazine.

Twenty-five years ago eager movie buffs filled theaters across the country for the debut of “The Misfits.” Shot entirely on location in and around Reno, the movie had all the makings of a blockbuster. Directed by John Huston and written by Arthur Miller, it starred Clark Gable and Marilyn Monroe, with Eli Wallach, Thelma Ritter, and Montgomery Cliff sharing the bill.

But movie-goers expecting a shoot ’em up Gable western or a sexy Monroe comedy were disappointed. Although some critics gave it four stars, others panned it. Still, it remains a classic.

The story was based on Nevada reality. In 1956 Miller, seeking a divorce, spent his six weeks’ residency in a cabin near Pyramid Lake. While there he met three Nevada mustangers who impressed him as being “the last three unreconstructed originals in the United States.”

So begins author James Goode in “The Making of The Misfits.” First printed in 1963 and republished this year, the book is a day-by-day account of the movie’s production, which brought some of filmdom’s best known figures to the Nevada desert. Here Goode describes the arrival of the Hollywood misfits.

JULY 18, 1960 — This morning, at nine o’clock, “The Misfits” company, directed by John Huston, began shooting a series of random Reno scenes devised by Arthur Miller to alternate with the title and credits and establish the setting of the picture. These title shots, made without the principal actors, might have been photographed at any time, but the plan is to shoot in strict script sequence throughout, to enable the actors to stay in the context of meaning as the intricate play unfolds; the day’s shooting also serves to bring the crew together as a unit under Huston. The crew itself was incredibly swift, setting up camera, lights, and sound within 15 minutes at each new location and striking in the same time, loading and unloading three large trucks of gear at each stop in 104-degree temperature, providing power for the heavy lights from a large gasoline generator.

The scenes appear to be an unrehearsed look at Reno but are not in fact. For one short sequence, showing a wedding dress revolving in the Virginia Street window of Joseph Magnin, the second assistant director, Carl Beringer, found aging Freddy Parker in a Commercial Row saloon, saw him as a perfect cinematic drunk, and took him back to the waiting camera. It was no good because Parker, off a bar stool, froze into unrewarding poses. Beringer found it necessary to spend $20 on whiskey before Parker could freely implement Huston’s idea, to whirl drunkenly in balletic parody of the revolving wedding dress.

The camera moved on to a pawnshop window, created by art director Steve Grimes, which displayed a sad collection of useless male artifacts traded in for another chance on the unremitting Reno slots; then to the slot machines themselves, anthropomorphic cast iron or carved wood replicas of western badmen, with the usual long chrome lever in place of one arm, each with plaster eyes more evil than the last. This surrealistic touch was followed by a look at long rows of the standard slot machines and crap tables in action in the gambling clubs, in Arthur Miller’s words “a sea of cold chrome.”

The title shots ended with a bride and groom being escorted by Reno Junior Chamber of Commerce-types in western dress into a “Black Mariah” with accompanying gunfire, and driven under the Virginia Street neon sign, RENO, THE BIGGEST LITTLE CITY IN THE WORLD. The bride closed the sequence by returning to her job as a blackjack dealer in the Mapes Hotel casino, still in her white wedding gown, the veil in place. The groom, Walter Ramage, returned to his office. Huston, in the first of a long series of appearances in the casino, celebrated the end of the first day’s shooting by winning $175.

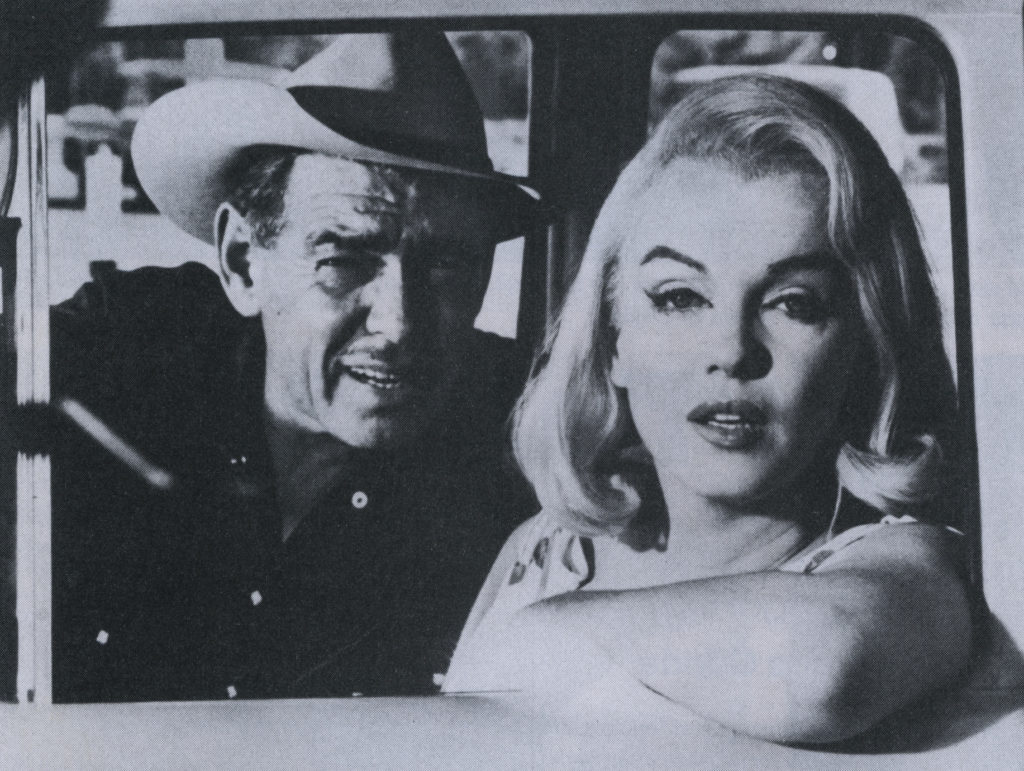

July 20 — Today’s shooting call, listing the cast and crew needed for the day and posted in the Mapes Hotel lobby, was for 8 a.m., an hour earlier than usual. The reason was a scene showing Clark Gable, as Gay Langland, saying good-by to a St. Louis divorcee at the Southern Pacific train station in the center of town. One of the first scenes in the picture, it called for the lady to board the train and wave goodby as the train pulled out. Since the cost of a special train would have been prohibitive, even if one had been available, it was necessary to use the Overland Limited heading west from Chicago to San Francisco, holding it for a few minutes longer than usual. A train heading east might have been more accurate, but there were none during daylight hours.

Playing opposite Gable in this brief scene was blonde Marietta Tree, socialite and friend of John Huston, and most famous for the Democratic political salon that she runs in her upper-Eastside mansion in New York. Mrs. Tree had not intended to appear in the picture, but had simply stopped off to see Huston on her way to San Francisco. The day before, Huston had interviewed a local actress who was to play the part of the departing St. Louis divorcee, and had decided against using her. Gable, Huston, and Mrs. Tree were talking later at lunch when Gable suddenly said, “Why don’t we have that one over there?” meaning that Mrs. Tree could very well play the part. Mrs. Tree protested, saying that she wasn’t an actress, and not the type. Gable replied that she was just the type he wanted.

As the train pulled in at 8:25, discharging passengers, Gable and Mrs. Tree began the farewell scene, establishing Gay Langland’s character as a Reno cowboy who has had frequent affairs with women in town for divorce actions, and also as a man who can’t be bought and who refuses to be tied down. Mrs. Tree, as Susan, said, “Will you think about it? It’s the second largest laundry in St. Louis!” Gay replied, “I wouldn’t want to kid you, Susan. I ain’t cut out for business …. ”

Mrs. Tree, as Susan, was crying as she boarded the train and waved good-by from a window as the train pulled out of the station. She said later that she was scared silly about the moving train; knowing Huston’s elaborate practical jokes, she feared that he had given the engineer instructions to keep right on going to San Francisco. But the train stopped after a few feet and backed up into position again for an additional shot. In this one, Guido (Eli Wallach), a garage mechanic, pulling up to a lowered signal at the track, sees Gay and invites him over to Harrah’s for a drink.

Completing the shot, with tiny microphones on sticks at ground level and inside Gable’s shirt, the crew struck the lights and moved on to the next location, a two-story frame house belonging to the Reno USO and chosen by Steve Grimes as a likely boardinghouse for Roslyn (Marilyn Monroe) and her friend Isabelle (Thelma Ritter). Monroe had not yet arrived in Reno, but she wasn’t required for the first shots at the USO.

The script called for the arrival of Guido in his garage truck to appraise Roslyn’s new Cadillac convertible, a present from her husband in Chicago. Roslyn, it seems, would like to dispose of both the Cadillac and the husband. Isabelle says in the script that Reno men keep running into Roslyn’s Cadillac just to start conversations, so it was necessary to pound dents into the body of the new car with a sledge hammer. The usual crowd of Reno onlookers winced with each blow, but the crew itself was calm, offering advice to the grip with the hammer.

Thelma Ritter appeared for the first time in this scene, her left arm in a sling and carrying a broken alarm clock in her other hand, and speaking in one of the memorable voices of the screen.

The afternoon was also marked by the arrival of Marilyn Monroe at the Reno airport. Arthur Miller, Frank Taylor, a United Artists publicity man, “The Misfits” still photographer, Al St. Hilaire, a few members of the Reno press, a newsreel photographer, and 200 fans were on hand when a United DC-7 landed at 2:45. In a preview of what was to happen throughout the filming of “The Misfits,” America’s oldest enfant terrible did not emerge from the plane for 30 minutes. No one seemed to mind, and everyone waited patiently as she walked to the passenger gate, accompanied by Miller, Rupert Allan, her press representative, and Sydney Guilaroff, who had arranged her hair on the plane. She looked very young in a white blouse and skirt, and was already in character as Roslyn in the upswept platinum wig that she would wear during the picture. There were a few words of welcome, a presentation of flowers by the wife and daughter of the governor, and Monroe was escorted to Taylor’s Thunderbird for a triumphant ride down Virginia Street to the Mapes Hotel. Taylor was hoping to get pictures for the wire services and newsreels of Monroe perched on the back of the open car under the sign, RENO, THE BIGGEST LITTLE …. He did, and Monroe disappeared into the Mapes and her suite on the top floor. It was later explained that the delay at the airport occurred because Miss Monroe was changing her clothes in the ladies’ room on the plane.

July 21 — Montgomery Clift and Kevin McCarthy both arrived in Reno today, McCarthy for a three-day appearance as Mr. Taber, Roslyn’s husband, who comes from Chicago to ask Roslyn to reconsider the divorce.

July 23 — ln his suite at the Mapes Hotel that afternoon, Huston tried to explain “for what,” and to tell why he had decided to direct “The Misfits.” As he spoke, he drew a succession of ink portraits of this writer, and smoked innumerable Gauloises cigarettes.

“I got the script in the mail with a letter from Arthur Miller. He was unbelievably modest. He asked me if it had any value. I read it and immediately cabled that I liked it very much ….

“What’s behind it? It is about people who sell their work but won’t sell themselves. Anybody who holds out is a misfit. If he loses, he is a failure, and if he is successful, he is rare. This movie is about a world in change. There was meaning in our lives before World War II, but we have lost meaning now. Now the cowboys ride pickup trucks and a rodeo rider is an actor of sorts. Once they sold the wild horses for children’s ponies. And now for dog food. This is a dog-eat-horse society.

“The part of Gay Langland is a point that should be underscored now, not as a preachment. It reveals itself dramatically. He’s the same man but the world has changed. Then he was noble. Now he is ignoble.”

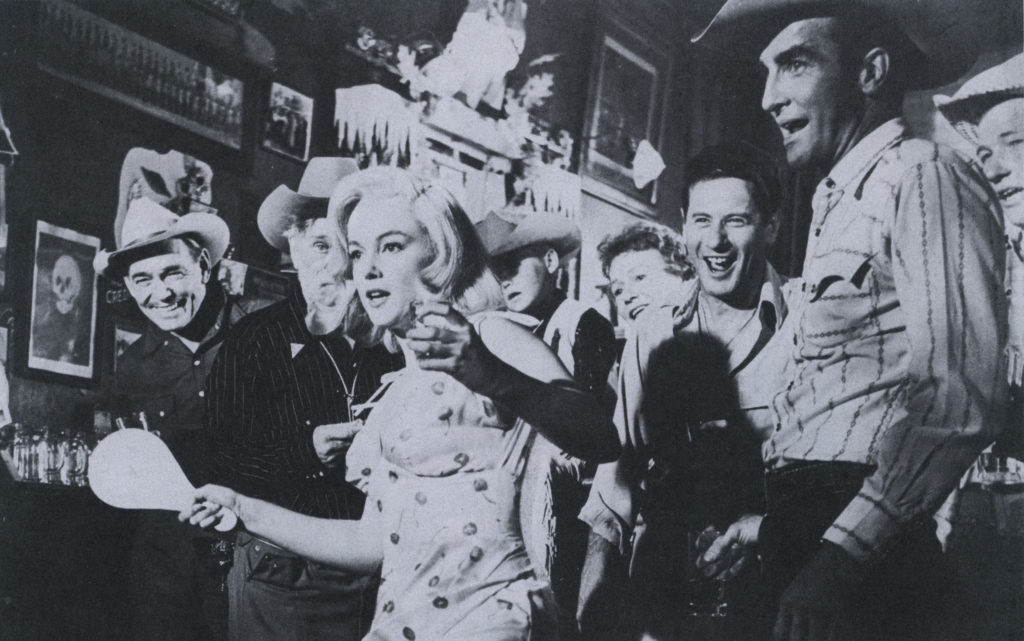

July 25 — After rushes, the party walked to Harrah’s Club on Virginia Street, where the company was shooting a scene from the script in which Gay and Guido meet Roslyn and Isabelle in the bar in Harrah’s. This marked the first time Gable had played opposite Monroe and the entire company was on hand.

It was also the first time in years that Harrah’s Club, open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, had been closed to the public. The stars emerged from their trailers parked at the curb, and policemen kept a crowd of 300 people from surging through the doorless air-curtain entrance. The atmosphere inside was realistic, jarred only in the bar where the lights, sound boom, and camera were already in place. A casual group of 75 extras, all hired in Reno for $10 a day, milled through the dice and roulette tables and around the slot machines, but did not play. The familiar sounds were absent, and even the air conditioning had been turned off to permit recording. The normal shift of Harrah’s dealers, pit bosses, and waitresses stood silently at hand, the dealers losing about $10 a day in tips, Bill Harrah losing an estimated $50,000 each day in gambling revenue in exchange for the references to his club in the script.

The scene began with Gable and Wallach on adjoining bar stools with their backs to the camera, Monroe, and Ritter. Langland’s hound, Tom Dooley, was beside a stool. In the script, Roslyn sees the dog and calls to it. Langland notices that his dog is missing, sees Roslyn, and advan·ces upon her. Guido and Langland are introduced by Isabelle, who has met Guido at the boardinghouse, and the issue is joined. Marilyn Monroe was very nervous, Tom Dooley was unmanageable, and the scene was long, but Huston got the company out of Harrah’s in a day and a half, a day and a half ahead of the estimated three-day shutdown, to Bill Harrah’s vast relief.