High-Flying Wayfinding

Summer 2021

Concrete arrows guided airmail pilots through Nevada’s deserts and mountains.

BY MARK WALKER

Imagine that you are the pilot of an open-cockpit biplane, flying from Reno to Elko with 300 pounds of mail. It is night in 1926 and you are relying on a recently installed innovation on the ground to keep on course over Nevada’s deserts and mountains. You have a strip map and compass and a railroad to follow in daylight. But at night these are useless. Instead of having the navigation equipment and air traffic control that keeps planes on course today, you follow a newly constructed route marked by orange concrete arrows embedded in the ground, each about 50 feet long and lit by beacons powered by acetylene gas or electricity.

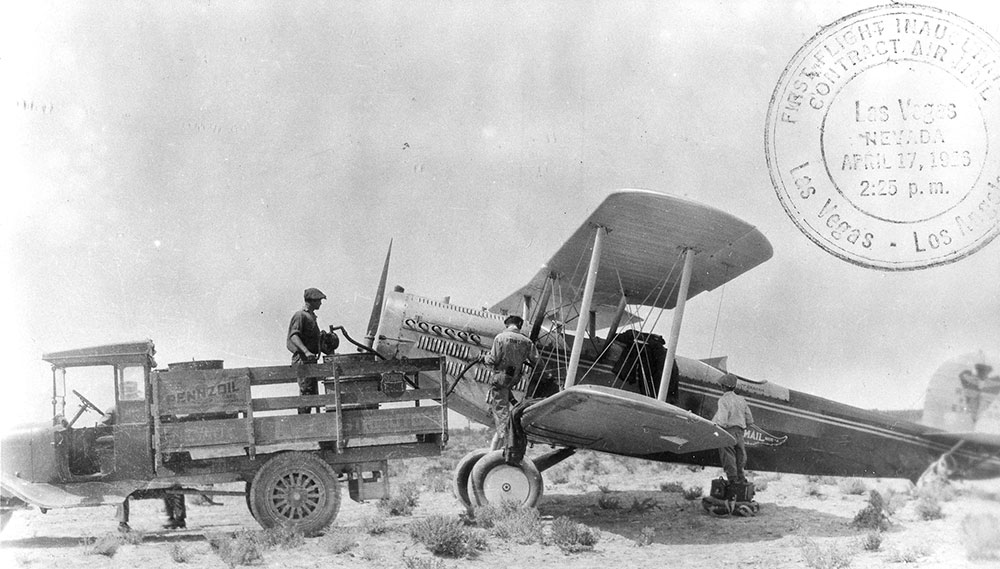

The arrows and beacons were part of the Transcontinental Airway, an air route established by the U.S. Airmail Service in the early 1920s. The Airway initially connected New York and San Francisco with stops in Reno and Elko and later expanded to connect Los Angeles and Salt Lake City, with a stop in Las Vegas. The U.S. Airmail Service supported the initial development to establish an airmail delivery system that spanned the country.

The arrows and beacons were part of the Transcontinental Airway, an air route established by the U.S. Airmail Service in the early 1920s. The Airway initially connected New York and San Francisco with stops in Reno and Elko and later expanded to connect Los Angeles and Salt Lake City, with a stop in Las Vegas. The U.S. Airmail Service supported the initial development to establish an airmail delivery system that spanned the country.

The pilots flew in every kind of weather imaginable and there were occasional hair-raising stories, such as this one about Reno pilot William Blanchfield. Blanchfield immigrated to the U.S. after serving as a pilot in Ireland during World War I and applied for citizenship. As an airmail pilot, he was assigned the Reno-Elko run in Nevada, and his exploits while delivering the mail became the stuff of legend.

“The Nevada State Journal” described one of his flights this way: “During the month of November 1922, Blanchfield made his phenomenal run from Elko on the wings of a hurricane. The thermometer registered 16 degrees below zero at Elko and the field manager there told him it was impossible to make the flight. But Blanchfield, with that soldier tradition of generations, demurred. He said that the mail must go. And he won. But the fight he made with the blizzard is still talked about in aviation circles.”

GROUND SUPPORT

The U.S. Airmail Service wanted to fly at night but recognized that pilots would be at enormous risk of straying off course and crashing. Radio technologies and navigation aids—other than newly drawn maps with descriptions of the routes—were not available, so mail pilots flew during daylight and landed to relay mail bags to trains, which could then travel at night. The combination of air and rail service was faster than rail service alone, but it did not take full advantage of the speed and directness of airplanes.

In 1923, the U.S. Airmail Service began experiments with night flights guided by a trail of concrete arrows and airfields lit by beacons on small sections of the Transcontinental Airway. Each arrow pointed toward the next waypoint and they were placed a few miles apart along the route, allowing pilots to navigate the way.

These tests were a success and the first night flights between Chicago and Cheyenne, Wyoming, were completed safely with no major accidents. The U.S. Airmail Service, still carrying mail with converted biplanes obtained from the U.S. Army, proposed that the arrow and beacon system be expanded. Two sections traversed Nevada, one linking Chicago and San Francisco with major airmail depots in Reno and Elko, and another between Los Angeles and Salt Lake City, which touched down in Las Vegas. By 1927, the U.S. Airmail Service had contracted with private air transport companies to carry mail night and day.

SIGNS OF THE PAST

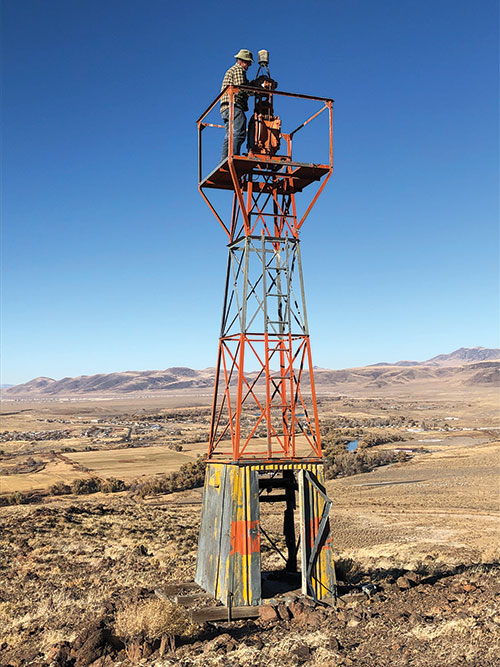

Many arrows and beacons still exist in Nevada, on playas, bluffs, and ridges along the routes between Reno and Elko and Las Vegas and Salt Lake City. The paint is most often worn away by nearly a century’s exposure to weather and Nevada’s sun, although some appear to have been repainted by unknown sources. With varying degrees of effort, you can reach many of the remaining arrows and look to the sky to imagine what it might have been like to navigate by these lighted arrows at night from a few thousand feet above.

The sites are a popular destination for a few adventurers every year. Most of the sites are accessible by dirt road and hiking, though roads to many are in very poor condition and some are on private or tribal land. Many of the roads used to build and maintain the sites still exist but cannot be driven, so this means hiking and climbing, sometimes in rough terrain.

As an example, it takes a modest effort and short climb to reach an eastward pointing arrow just south of the Truckee River near Mogul in northern Nevada. Another, pointing north across a distance of about 9 miles to McCarran International Airport, can’t be reached without scrambling up about 250 feet of fairly steep loose rock and scattered brush to the top of a knoll. Access is just outside the fence of a recreational vehicle dealer near Henderson. On a hot day, the trip to that bent arrow at the top can be challenging. It is best to bring food and water for the short hike, even though you can look down on Interstate 15 and a commercial district flanking the knoll on each side.

In person, the arrows can almost be mistaken for abandoned mobile home foundations, except for two key features. Most have a rectangular pad slightly larger than the arrow itself that housed an acetylene generator or electrical connection to light the beacons, and all have a prominent arrowhead at one end. Some, like the arrow in Mill City in Pershing County, are even bent to let pilots know to change course to reach the next step on the route.

In person, the arrows can almost be mistaken for abandoned mobile home foundations, except for two key features. Most have a rectangular pad slightly larger than the arrow itself that housed an acetylene generator or electrical connection to light the beacons, and all have a prominent arrowhead at one end. Some, like the arrow in Mill City in Pershing County, are even bent to let pilots know to change course to reach the next step on the route.

None of Nevada’s arrows and beacons function. Some, like those inside posted areas at Pershing County’s Derby Field, Winnemucca’s Municipal Airport, and Battle Mountain’s Lander County Airport have well-preserved towers. At most other sites, the sheds that housed acetylene gas or electric relays have been removed or vandalized in the nearly 100 years since the system was built.

The arrows and beacons were in service for about a decade, replaced by radio communications and better navigational instruments. However, the arrow and beacon trail built faith that airplanes could be a useful tool for commerce, and these successes became the foundation for commercial aviation. The sections that traversed Nevada were an important part of a national test to prove that airplanes could be a cost-effective way of moving people and materials around the world.