Rocks and Minerals in the Silver State

Summer 2021

Digging in the Nevada dirt has rewards beyond any dollar value.

BY MEGG MUELLER

Almost three-quarters of the Earth is covered by water, some 71 percent. For anyone who has looked upon the vistas and mountain ranges of the Nevada landscape, that can be a mind-boggling thought. Our arid nature comes at a cost sometimes, but boy, that land provides wealth that goes way past bank accounts. Getting down—and maybe dirty—in the hills of our state is one of the easiest, least expensive, and most rewarding pastimes you’ll ever find.

WHERE THE RED STONE GROWS

Once, the ground in Nevada was littered with nuggets of gold and rich veins of silver, at least the history books tell us so. It’s a little tougher to find those precious metals lying about today, but if a beautiful gemstone will do, look no further than Garnet Hill in White Pine County.

If an entire hill named for the beautiful red gem isn’t enough, it’s a Bureau of Land Management area replete with an accessible bathroom and four picnic sites with grills. But let’s be honest, you didn’t come here for the picnic—you came for the garnets.

Almandine garnets are made up of iron aluminum silicate and are generally a rich dark color. Flashes of red often burn within the multifaceted stones that can be found lying on the ground. You read that correctly; they can be found lying on the ground as well as in the rhyolite rocks that populate the hillsides.

Locating the gemstones within the rhyolite can be tough and requires a rock hammer and close inspection. Don’t smash willy-nilly or you can easily bust up the gems you seek. Looking for rocks with holes or pockets is a decent indicator, albeit not foolproof. The garnets found lying on the ground have extricated themselves from these pockets, so it can follow there will be others in the slabs of light-colored rhyolite, but not always.

Close inspection is also required for finding the loose stones. Traveling further away from the areas close to the parking lot is an obvious tip, as is look in gullies and anywhere it appears water has been flowing. The stones can get picked up and deposited this way. I found two such gems near one another, but fully admit there were also a lot of berries picked up and perhaps even a piece of deer poop or two. Wear gloves is another tip I gladly share.

I didn’t find anything on my first couple visits to Garnet Hill, but both times I was on a tight schedule. This time, I simply wandered down the slopes of the hill determined not to leave until I found something. I spent a lot of time on my knees, digging with my rock hammer, seeing glints of crystals, and sitting back to watch the goings on at the massive Robinson Mining District copper mine that is visible from much of Garnet Hill. It was a beautiful day, cool at 7,000 feet elevation but not cold. Even without stones, it was worth the trip.

SPARKLES IN THE DESERT

One of the easiest rock hunting sites to access is located in Weeks, off 95A between Silver Springs and Yerington in Lyon County. Not only do you not need any special vehicle considerations, if you go on a sunny day, the glint off the selenite crystals will do its best to blind you.

Selenite is a variety of gypsum and specimens have been found up to 39 feet long in caves in Mexico. You likely won’t find anything that long, but scattered all over the ground the mostly clear, often perfectly cleaved material sparkles beautifully in the sun. The mineral is fairly soft, a 2 on the Mohs hardness scale which means you can scratch it with your fingernail. It has some flexibility but can be broken, especially if you find a flat piece, of which there are many. Selenite is generally clear—depending on the other trace minerals that might be in the material—and has been used as window panes.

In the world of crystal lore, selenite is said to have properties that aid in positive energy and clearing of stagnant emotions. Selenite wands are popular with people who use crystals for energy work, and they are incredibly beautiful. Whether you ascribe to crystals and their mystical properties, there is no mistaking the elegance of selenite.

Selenite is found across Nevada: I have material from the Weeks site, and also from Gold Butte National Monument in southern Nevada. It’s a favorite of kids, due to its easy-to-spot sparkly properties.

WHAT A WONDERFUL WORLD

I’ve been a wee bit obsessed with wonderstone since I first saw it decades ago. Bands of orange, red, brown, purple, creams…it was as if the rainbow-striped hills I’d grew up seeing were presented to me in miniature. When I discovered Wonderstone Mountain (or Rainbow Mountain, as it’s also been called) was just under an hour east of Fallon, it quickly became my favorite haunt.

For my recent trip, I enlisted the help of the Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology at the University of Nevada, Reno. Geologist Rachel Micander and Graphic Designer Christina Clack joined me for a day wandering the hills and talking all things rocks. Growing up in the Sierra Nevada foothills, Rachel is an eager teacher and veritable font of information.

“I recently heard a geologist friend say that ‘wherever you go, there is always geology.’ That’s the cool thing—there are rocks, remnants of rocks, and the processes that form rocks and landscapes all around us,” she says. “There is always something new to discover—different rocks and minerals to pick up on hikes, and fascinating geologic formations to study. The Great Basin is a remarkable place to study geology.”

“I recently heard a geologist friend say that ‘wherever you go, there is always geology.’ That’s the cool thing—there are rocks, remnants of rocks, and the processes that form rocks and landscapes all around us,” she says. “There is always something new to discover—different rocks and minerals to pick up on hikes, and fascinating geologic formations to study. The Great Basin is a remarkable place to study geology.”

Driving to the Grimes Point/Hidden Cave Archaeological Site turnoff, we head east to find orange hills capped by rhyolitic tuff, which is indicative of the myriad kinds of volcanic activity the area has witnessed, Rachel explains. Suffice to say, all technical information from here on out comes from Rachel. Going rockhounding with a geologist is like making snacks with Julia Child: you learn more about a supposedly simple task than you could have ever imagined possible.

As we approach the orange hills, it’s obvious we’re in the right territory because the ground is covered in material of every color and size. Some of the material is covered in what Rachel mentions is called desert varnish or patina, but is actually a microorganism that grows on the rocks, painting them black. The unmistakable Liesegang bands characteristic of wonderstone are everywhere. The bands are the result of what Rachel calls the perfect recipe: the rhyolitic tuff is altered by hot waters that have deposited pyrite and quartz, while rainwaters penetrated the rock and oxidized the pyrite forming stripes of red hematite, and orange brown goethite.

Christina is taking photo after photo, and it’s obvious the wealth of material is going to consume most of her cameral roll. Brilliant patterns made up of stripes, squares, and circles appear as if painted by artists. The samples on the ground are enough to make my head dizzy, but the large rock formations are staggering in their complexity and beauty.

We stand with rock hammers in hand, but no one wants to disturb the massive rock canvases so we gather some souvenirs from the ground. I’m only slightly embarrassed to note I am the only one who brought a bucket.

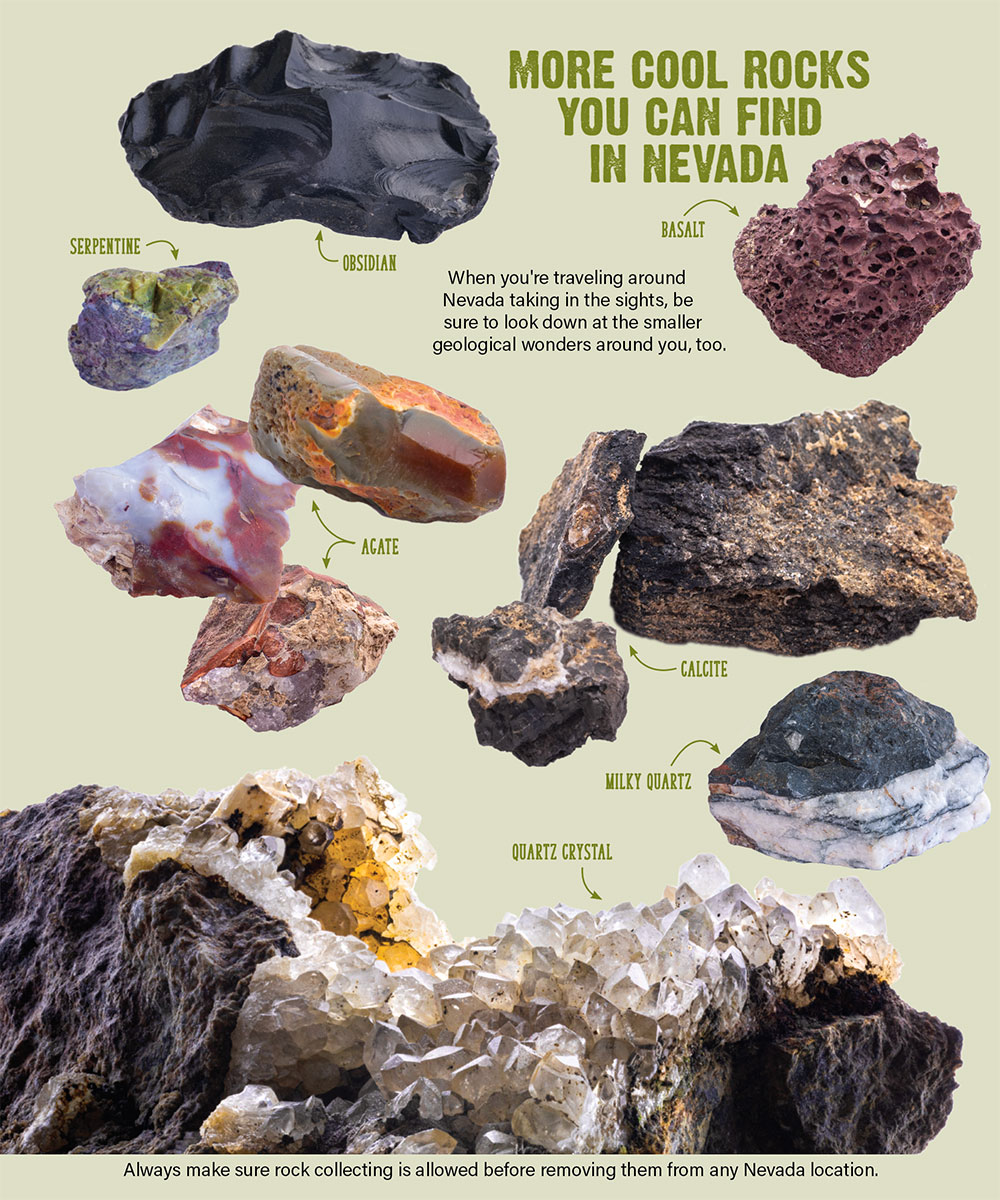

We move on, knowing there are other deposits nearby and hoping to find other rocks. Agate, green rhyolite, and even jasper have been found in the area, along with volcanic bombs that Rachel says are most likely from the nearby Soda Lake. The small rocks were formed when lava was ejected from ancient volcanos, landing miles away.

Eventually we decide we’ve gathered enough samples, hiked enough hills, seen enough lizards, and talked about rocks enough for one day. And what a great day it was.

JUST LOOK AROUND

The amount of exciting material found across Nevada is one of the things that makes this state a rockhounder’s dream. Rachel thinks of a few additional reasons.

“I think one of the things that makes rockhounding in Nevada so special is the amount of public land we have in this state. With the right knowledge and resources, It is so easy to get out and explore our public lands,” she explains. “The desert climate also makes for a great rockhounding experience. With so little dense vegetation, the rocks can be found that much easier.”

Rockhounding can be easy, and it can be frustrating. But it’s so simple a thing, to do a little research and point your vehicle in the right direction. At the end of the road—or perhaps the top of the hill—it’s just you and your thoughts as you walk through serene landscapes, gathering beautiful stones, and, hopefully, a sense of wonder at how beautifully made this state truly is.

DIG IT!

Before you go, know what you’re looking for, and whose land you’ll be on. As ever, bring water, the right tools, and make sure your vehicle is equipped for the roads you plan to traverse. Some useful information can be found here:

Bureau of Land Management

blm.gov/Nevada

Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology

nbmg.unr.edu, 775-784-6691

Rockhounding Nevada, 3rd edition

By William A. Kappele, revised by Gary Warren

Garnet Hill

blm.gov/visit/garnet-hill