Fast Friends

Summer 2024

How jai alai helped build Las Vegas’ Basque community.

BY MARK MAYNARD

Northern Nevada has been home to a thriving Basque immigrant community for more than a century. In communities like Elko, Winnemucca, and Reno, locals and visitors frequently gather at former boarding houses and 100-year-old restaurants for a family-style meal and a potent Picon Punch cocktail. However, not all of Nevada’s Basque diaspora communities have such a long-lived tradition.

A DIFFERENT KIND OF DIASPORA

The Lagun Onak (Good Friends) Basque Club of southern Nevada is a more culturally isolated group of Basques. Unlike their northern counterparts—who owe their culinary and cultural heritage to generations of high-desert sheepherders, innkeepers, and cowboys—many of the founding members of Lagun Onak arrived in the neon-bathed casino town of Las Vegas in the 1970s and ‘80s as professional athletes.

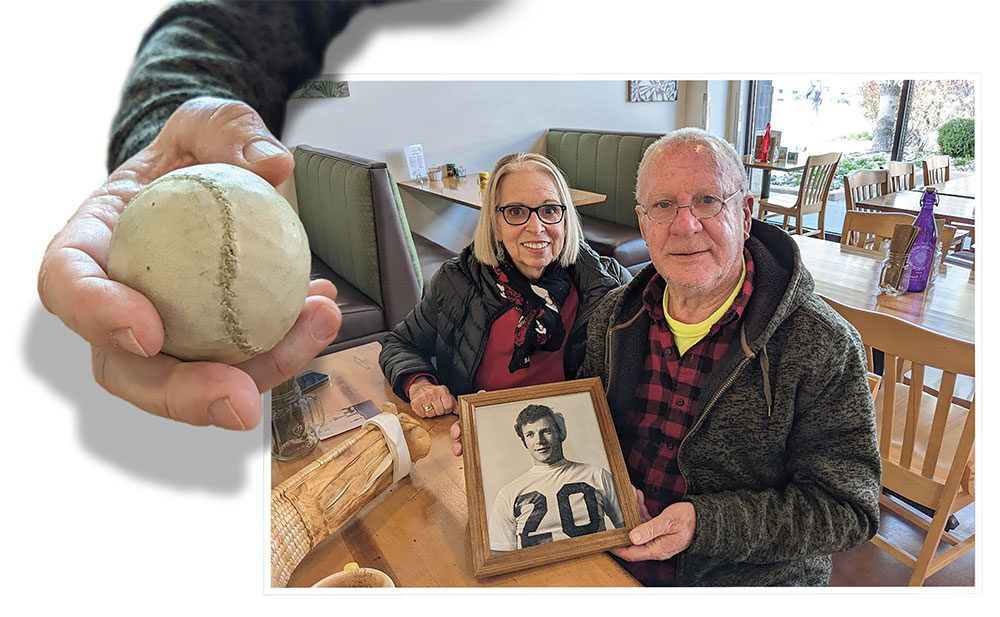

Jai alai is the national sport of the Basque country. A high-speed, ball-and-basket game, it is played on a racquetball-like court called a fronton. The hard, goatskin-wrapped rubber ball—pelota—is slightly smaller than a baseball and is propelled by a woven basket—a cesta—worn on the players’ hands. The Guinness Book of World Records recognizes jai alai as the fastest moving ball sport, clocking the record speed of a pelota at 188 mph.

Jai alai is an exciting spectator sport ready-made for bettors. Much like horseracing, it uses a pool-based, pari-mutuel system where bets are placed on who will finish in the first three spots. The game was popular on the East Coast but untested in Nevada, where it would compete with legal casino gaming.

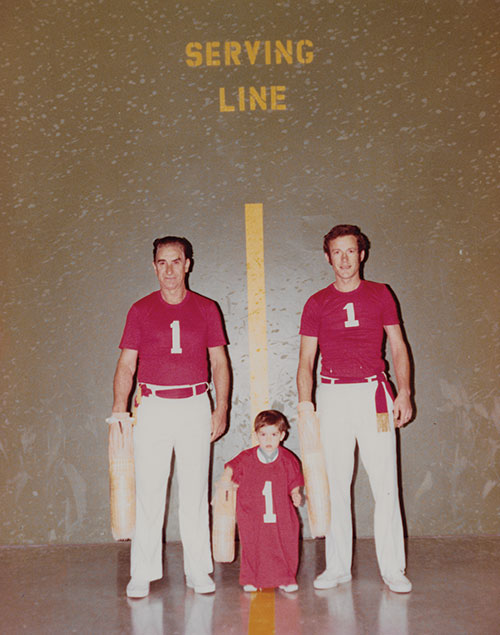

In Las Vegas, MGM owner Kirk Kerkorian saw an opportunity to corner the market and built a 2,000-seat fronton in 1974 to be a centerpiece for his new gaming venture. Thus, at the MGM Grand Casino’s invitation, the early 1970s saw a small wave of Basque athletes moving to Las Vegas from Spain and other diaspora strongholds.

When Josu Aldecoaotalora and his wife Pilar stepped off the plane, they were overwhelmed by blinking lights and ringing bells. Aldecoaotalora, a native of the Spanish Basque Country, had been living abroad for years playing jai alai in Indonesia and the Philippines. Now the couple was arriving after midnight in their new hometown of Las Vegas.

“All of the slot machines in the airport,” says Pilar, describing her first few moments in America. “That was the first shocker.”

AMERICAN DREAM IN THE DESERT

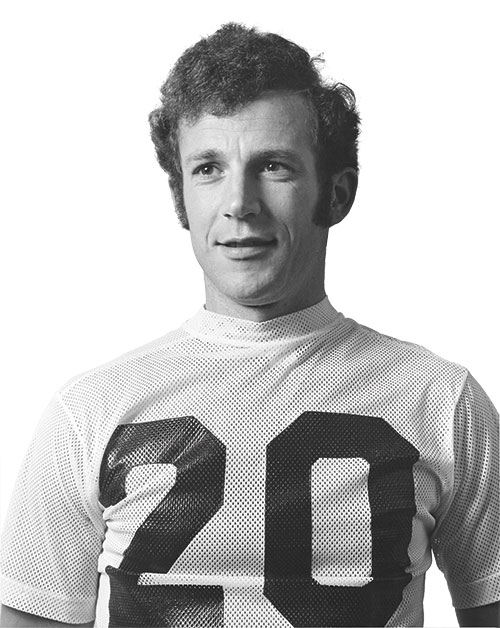

“Growing up, I had a lot of pride in the game,” says Jose Echenique. His father came from Spain and was Josu Aldecoaotalora’s teammate at the MGM’s fronton. “I have memories as a child, in the locker room, watching from the back.”

Echenique remembers growing up in “small Vegas” in the 1970s. His community was filled with jai alai players and their families who had immigrated from around the world.

“Many players envisioned their sons—coming up as the first-generation Americans—would take over the sport they started for us,” says Echenique. He remembers his father trying to teach him how to scale the wall and other game techniques. The senior Echenique planned on playing in Las Vegas for 10-15 years, saving his earnings, and then returning to his ancestral home in the town of Zugarramurdi (located near the French border).

Jai alai caught on in Las Vegas for a while, and though the casual fans didn’t understand the nuances of the sport, the arena was a place to be seen. Pilar remembers seeing Sylvester Stallone and his then-girlfriend Susan Anton in the crowd one night, and her husband remembers the impressive scale of the fronton.

“Everything was big,” he says. “American big.”

And then, after a 10-year run, Las Vegas jai alai shut down overnight. However, the sport’s end did not come as a surprise. Attendance had been declining for years, and the arena’s space became more valuable for Las Vegas’ burgeoning convention business. In 1983, the fronton was permanently converted into a meeting space, leaving the players without a sport.

Aldecoaotalora remembers the day of the last games when players were told jai alai would close that night. He went to the showers, and by the time he emerged in his street clothes, the net that separated the court from the spectators was being torn down. Professional jai alai would never again be played in Las Vegas.

“They all went in to go play and all the doors were locked,” remembers Echenique, whose father was devastated by the closure.

Out of a job before their contracts expired, 29 of the players sued MGM for insurance and back pay, which ultimately reached a settlement. The former players now faced a difficult decision: find casino or construction jobs in Las Vegas or head east where frontons still operated from Connecticut to Miami. If they didn’t find work, they faced expired visas and deportation.

CREATING A COMMUNITY

Near the end of jai alai’s tenure in Las Vegas, a pool contractor named Jose Mari Beristain helped found the Lagun Onak Las Vegas Basque Club. Beristain emigrated from the Basque Country to Idaho in 1958 with his mother, brother, and sister. They came to join his father, who had been a sheepherder in the U.S. for the past decade. As an adult, Beristain found his way to Las Vegas, where he befriended many jai alai players who hailed from his home country.

The Aldecoaotaloras became members of the club, as did Echenique’s father. Sister Sue Laxalt (sibling of former Nevada governor and U.S. Senator Paul Laxalt and Nevada literary lion Robert Laxalt—all first-generation Basque Americans) was an early club supporter.

When jai alai shut down, players like Echenique Sr. felt alone in an unfamiliar country. Young men who had arrived without family had focused their time on playing jai alai. With the sport gone, they found kinship in Lagun Onak.

“He felt very abandoned and alone,” says Echenique. “I’m not too sure how well he would have done without that community in arm’s reach.”

For years, Echenique has campaigned for a gathering place for the Las Vegas Basques. He wants to buy a building and open a restaurant and bar, following the lead of the city’s Italian American Club. He hopes to pool resources with former teammates.

To this day, the club has no official place for gatherings. They often meet in parks and other outdoor spaces, though they avoid the searing months of Las Vegas summers.

After serving as president of the club for almost 40 years, Jose Beristain died in 2021. His daughter Amaya has since taken over as president. It is challenging to sustain and grow membership.

“Kids grew up and moved on,” says Amaya Beristain. There was a revival for a short time, however, as she says, Las Vegas has too many distractions for a younger generation.

“Unfortunately, my generation is getting older,” says Echenique, noting that his son proudly displays a Basque flag in his bedroom. “We drifted. We’re all trying to come back.”

This summer, he and his son will travel to the Basque Country to visit his father, who now splits his time between Spain and Las Vegas. Echenique’s son will meet his great-grandmother, and for the first time, four generations of the Echenique family will gather in the Basque Country.

Echenique hopes that his father’s dreams of a place for Basques to gather in Las Vegas comes true. Perhaps southern Nevada can build upon the Basque camaraderie found in the northern part of the state. Maybe, someday, the sound of pelotas will again echo in the frontons, and a new generation of jai alai athletes will entertain diehard fans—maybe some of whom have a few good bets placed.