Rainbow Canyon

Summer 2024

Take a scenic drive through Nevada’s most colorful corridor.

Take a scenic drive through Nevada’s most colorful corridor.

By Cory Munson

As a 30-something-year Nevada resident and a writer for Nevada Magazine & Visitor Guide, I’ve spent a lot of time on the road. I can safely say I have been on every major state route and highway, not to mention countless graded backroads and washed-out two-tracks. Over the years, a few routes have become favorites, and I always look forward to taking or recommending them. These include State Route 722, between Middlegate and Austin, and State Route 486, which passes through the Schell Creek Range behind Ely and McGill. However, at the top of my list is State Route 317, the road that ribbons through Rainbow Canyon.

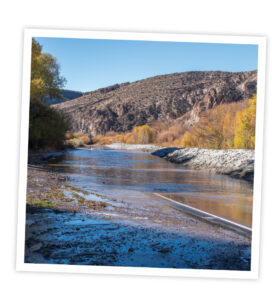

The canyon—located a few minutes south of Caliente—certainly earns its name. Its towering rock walls display a blend of earth tones offset by bands of rust-red rock. Green junipers and white rabbitbrush run upslope from the road with cottonwoods and aspens—orange and yellow in the fall—lined along the valley floor.

RAILROADS AND FLOODS

RAILROADS AND FLOODS

The waterway that runs through (and carved out) Rainbow Canyon is the Meadow Valley Wash. This temperamental stream begins 40 miles northeast of Caliente at Spring Valley State Park. After passing through the canyon, it empties near Moapa and—eventually—Lake Mead.

Meadow Valley Wash is prone to seasonal flooding. Those who live near it must adapt to frequently submerged roads and the potential for destructive flash floods. Unfortunately for early-20th-century railroad developers, Rainbow Canyon was unavoidable while constructing the Salt Lake City to Los Angeles line.

It took workers three years to complete the canyon’s 80 miles of rail and 10 steel bridges. The first railroad (foreshadowing) was placed right on the canyon floor—the lowest possible elevation—alongside the Meadow Valley Wash.

In 1907, a massive flood wiped out 23 miles of track and destroyed three bridges. Stakeholders questioned whether it was worth rebuilding—no doubt there would be more floods—and looked for a way around the canyon. But there were no other options: Any detour would be cost-prohibitive and add dozens of miles through barren desert without water, towns, or preexisting roads. All they could do was build the line higher up the canyon wall.

On New Year’s Eve 1909, another flood swept cars and tracks miles down the canyon, destroying millions of dollars in engines and supplies. The U.S. rail network slowed to a crawl as westbound cargo locked up in Salt Lake City in what papers called one of the greatest railroad catastrophes in American history. However, with few alternatives, the railroad had no choice but to rebuild at an even higher elevation, adding 10 tunnels and 13 new bridges.

Today, the busy Salt Lake to Los Angeles line still runs through Rainbow Canyon. Thanks to modern engineering, floods are nowhere near the danger they once posed.

Nowadays (unless a freight line is passing through) the canyon is quiet and peaceful. During your drive, you’ll probably feel like you have the whole place to yourself: the water to one side, the rail to the other, and the winding road ahead. It’s a wonderful experience, and while there’s no wrong way to do it, what follows are my suggestions for those looking to experience Rainbow Canyon for the first time.

THERE AND BACK AGAIN

Although a road passes through the entire canyon, visitors should start in Caliente and then drive as far as Elgin before turning around where the pavement ends. All told, it’s about a 45-mile round trip.

As mentioned, floods and washed-out roads are a reality in the canyon. The best time to visit is during the driest part of summer. Check road and weather conditions before making the trek: You might come across a few feet of water on the road that will force you to turn around.

That said, with its bridges, side canyons, ranch houses, and multi-hued cliffsides, Rainbow Canyon is about as picturesque as it gets in Nevada. There are plenty of scenic pullovers during the drive but be sure to visit the two sites that bookend the trip.

Kershaw-Ryan State Park

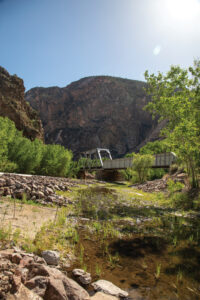

Three miles south of Caliente, this state park marks the northern edge of Rainbow Canyon. After a short drive, you’ll be in a 6-acre grove in near-perpetual shade—partly from the cottonwood and elm trees, mainly from the surrounding canyon walls. Stop here for a picnic or to escape the summer heat: Temperatures are usually around 10 degrees cooler here.

This lush glen used to be the Meadow Valley Wash Ranch. The Kershaw family owned it and then sold to a cattleman named James Ryan, who later donated it to the state. In 1934, the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) built picnic areas, trails, and other facilities. The park opened a year later.

A 1984 flood wiped out most of the infrastructure, shuttering the park for 13 years. Kershaw-Ryan is fully operational today, offering great camping areas and trails that grant beautiful views of the canyon below (see front cover of this issue).

Elgin Schoolhouse

Elgin Schoolhouse

This quaint country schoolhouse sits at the end of the 22-mile road.

By the early 1900s, Rainbow Canyon was a 30-mile string of homesteads with enough children to justify its own schoolhouse. The perfect place to build the school was at centrally located Elgin, a train depot with its own telegraph office. The county built the single-room schoolhouse in 1922, which operated until 1967. In 2005, the state acquired the property and dedicated it as the Elgin Schoolhouse State Historic Park.

Today, visitors can enjoy lunch in the shade and admire the old building. If you’d like a tour of the inside, contact the rangers at Kershaw-Ryan State Park.

GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

Rainbow Canyon has several points of historic note. Keep in mind that little remains of the following, but hopefully these details add some color to your journey.

Luxury Resort

Around 1.5 miles south of Kershaw-Ryan, the canyon widens into a meadowy bend that was once the Conaway Ranch. The Conaways settled there in the 1860s and built a multi-generational farming empire before selling their land to Howard Hughes in 1970. After Hughes died in 1976, his estate sold the 250-acre parcel to another developer planning to build Lincoln County’s hottest luxury destination: The Rainbow Canyon Ranch Resort.

When completed, the complex was to feature a condominium village, two luxury hotels, a casino, and a 36-hole golf course. The master plan even called for a movie theater, rodeo arena, horse track, cultural center, country club, and a shopping district.

None of that happened. Or, at least, most of it didn’t. In the early 1980s, the developer dug out the resort’s plumbing system and completed nine of the 36 holes. Then, the 1984 flood wiped out any hope for a resort, and the land returned to nature.

Ancient Remains

Rainbow Canyon is home to various pictograph (painted) and petroglyph (carved) sites, including one wall—located up a side canyon—that features faded red-orange pictographs. On the cliffside opposite the pictographs is a small hollow where, in the 1930s, archeologists—with the help of CCC crews—excavated artifacts dating back to 3000 B.C.

People have lived in Rainbow Canyon for more than 10,000 years. Over those millennia, innumerable cultures used the area to hunt or shelter. Other bands, like those belonging to the Fremont and Southern Paiute, took advantage of the floodplain to plant corn, squash, beans, and sunflowers.

Nobody knows which specific people made the pictographs, but they stand as a testament to the eons-long use of this canyon.

Ghost Town Utilities

Around 8 miles south of Caliente, near Mud Spring Canyon, is the site of a powerplant and (a bit further down the road) water pump that served Delamar. This mining town, located just on the other side of the mountain, grew to around 3,000 people in 1897 and thrived for a decade.

In its time, Delamar was infamous for its high fatality rate due to silicosis, which workers developed after breathing in fine particulate—called Delamar Dust—that came off the dry stamp mills.

Today, the town is a bit difficult to reach—OHV vehicles are highly recommended. However, it’s one of the state’s most expansive and impressive ghost towns. Visitors will find countless mine and mill ruins, hundreds of foundations, and many structures only missing a wall or two. There’s even an alleyway (how many ghost towns can claim that?).