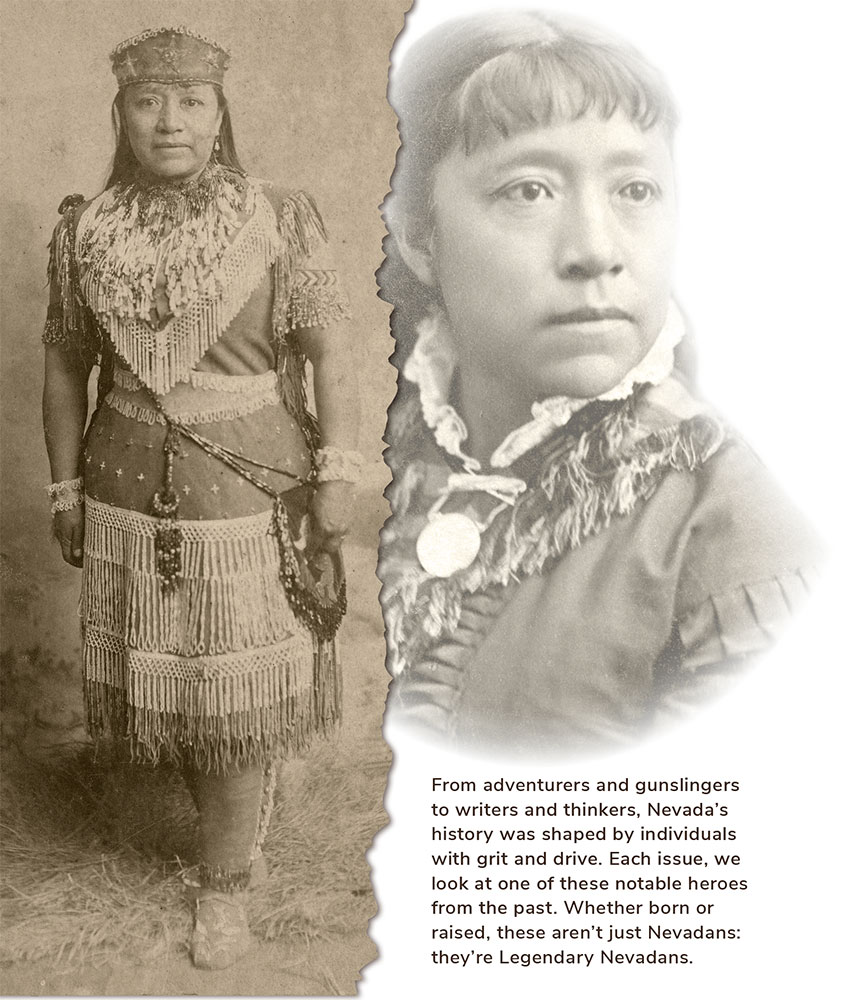

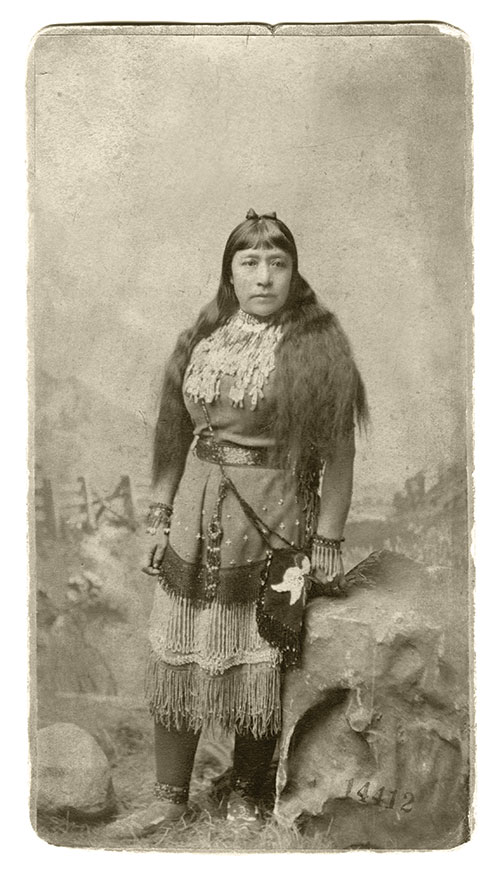

Sarah Winnemucca

Winter 2022-2023

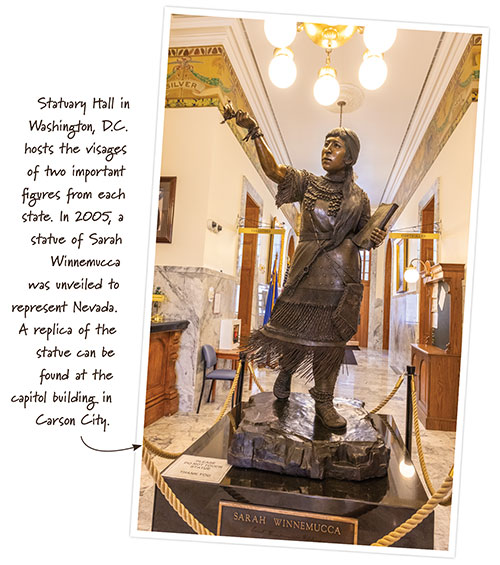

Meet the writer, teacher, and advocate who dedicated her life to Paiute rights.

Sarah Winnemucca was born around 1844, near what is today Lovelock. Her name at birth was Thocmetony, and she was a daughter of the leading family of the Kuyuidika-a—a band of the Paiute people.

Within a year of her birth, Winnemucca’s grandfather encountered John C. Frémont—one of the area’s first white explorers—at what is now Pyramid Lake.

Winnemucca’s grandfather believed the coming of white settlers portended good things and attempted to create friendly relations between the Paiute and the new arrivals. His good nature and status earned his family limited privileges, which included opportunities for the young Winnemucca to grow up in American settlements.

Winnemucca learned the customs, mannerisms, and dress of these new people. She also learned English and proved to be a talented speaker and writer.

She would forever straddle two worlds, but she would never be entirely accepted in either. She could wear formal attire and attend dinner parties, but her Paiute blood would forever make her an outsider. Even her own people found it difficult to relate to her privilege and relatively lavish lifestyle.

TENSIONS RISE

Winnemucca’s life coincided with the U.S.’s westward expansion into Nevada. By the time she was an adult, the Paiute people had lost much in their way of life and resided on reservations in the northwestern Great Basin.

The discovery of silver in western Nevada resulted in a stream of settlers in the Paiute’s territory. The massive migration disrupted their access to hunting grounds and pine nut groves, and the Paiute were forced into hunger.

Despite attempts by Winnemucca’s family to avoid violence, tensions rose. In 1859, two Paiute children were kidnapped by white settlers. The girls’ families found and killed the captors, prompting a group of 100 militiamen to attack the Paiute to put down an apparent uprising. Winnemucca’s cousin Numaga did not want war, but he led his people into battle and defeated the militia at Pyramid Lake.

Soon, 700 soldiers were dispatched from California, and the Paiute coalition was brought down. By 1864, most of the Paiute in Nevada had been placed on reservations at Pyramid Lake and Walker River.

A VOICE FOR CHANGE

When Winnemucca arrived at the Pyramid Lake Reservation, she discovered the federal agents were withholding food and supplies. With the help of her brother, she asked an army captain for better conditions and was invited to bring her people on a 300-mile trek north to Fort McDermitt.

At Fort McDermitt, Winnemucca became an interpreter. Her ability to speak Shoshone, Paiute, Washoe, English, and Spanish was rare, and combined with her ability to read and write, allowed her to find work.

While at the fort, the 27-year-old Winnemucca wrote letters about conditions inside the reservation. Her clear, frank descriptions were compelling, and the letters were soon reprinted in newspapers and books across the country.

While at the fort, the 27-year-old Winnemucca wrote letters about conditions inside the reservation. Her clear, frank descriptions were compelling, and the letters were soon reprinted in newspapers and books across the country.

Winnemucca and her family became symbols of the Paiute struggle. She moved her work to the stage and gave lectures in Virginia City and San Francisco. In 1880, Winnemucca brought her family to Washington D.C. to meet the president and make him aware of problems on the reservations.

Throughout the 1880s, Winnemucca gave hundreds of lectures and wrote countless letters advocating for change. In 1883, she published her book “Life Among the Piutes: Their Wrongs and Claims.” This was the first book to be published by a Native woman.

WINNEMUCCA TODAY

WINNEMUCCA TODAY

While her efforts are celebrated today, they were not nearly as effective as she hoped. Although she did raise public awareness, nothing really changed. People were still displaced and treated as second-class citizens, and mismanaged reservations

became a fact of life for a new generation of

Native Americans.

Winnemucca was a polarizing figure among the Paiute. She did not act, speak, or live like them, and openly preferred living among the whites. For all her claims of representing their interests, daily life for them did not improve. She promised much but delivered little, though perhaps she often only repeated unkept promises made by American politicians.

Apart from her life as a speaker and a writer, Winnemucca was also a talented teacher. Across many reservations and federal schools, she worked to give native children the same access to literacy and language that had allowed her to be a voice for the Paiute.