A Solitary Goal

May – June 2017

The Nevada State Prison Preservation Society Aims to Protect the Past.

STORY BY ROBIN BATES

PHOTOS COURTESY NEVADA STATE PRISON PRESERVATION SOCIETY

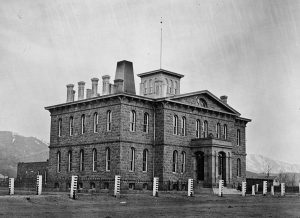

During its 150 years of continuous operation the Nevada State Prison in Carson City played a significant role in the history of Nevada, protecting its citizens, influencing architecture, and amassing an impressive list of historically significant events. The prison now sits idle after closing its doors on May 12, 2012.

Today, work is underway to make this landmark a historical destination where the past will be brought to life and interpreted through exhibits, tours, and lectures. The Nevada State Prison Preservation Society (NSPPS) is the nonprofit organization leading the effort. In 2015, the Nevada Legislature expressed its support of this project through the passage of Assembly Bill 377. Also in 2015, the prison was approved for listing on the National Register of Historic Places. Telling the stories that illustrate the cultural importance of the Nevada State Prison is the society’s priority.

FIRST ON THE BLOCK

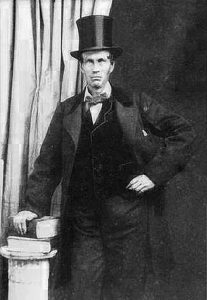

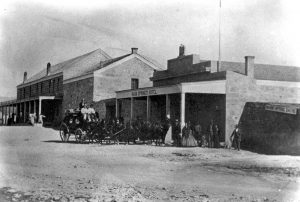

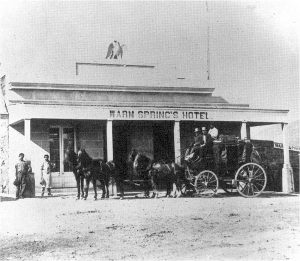

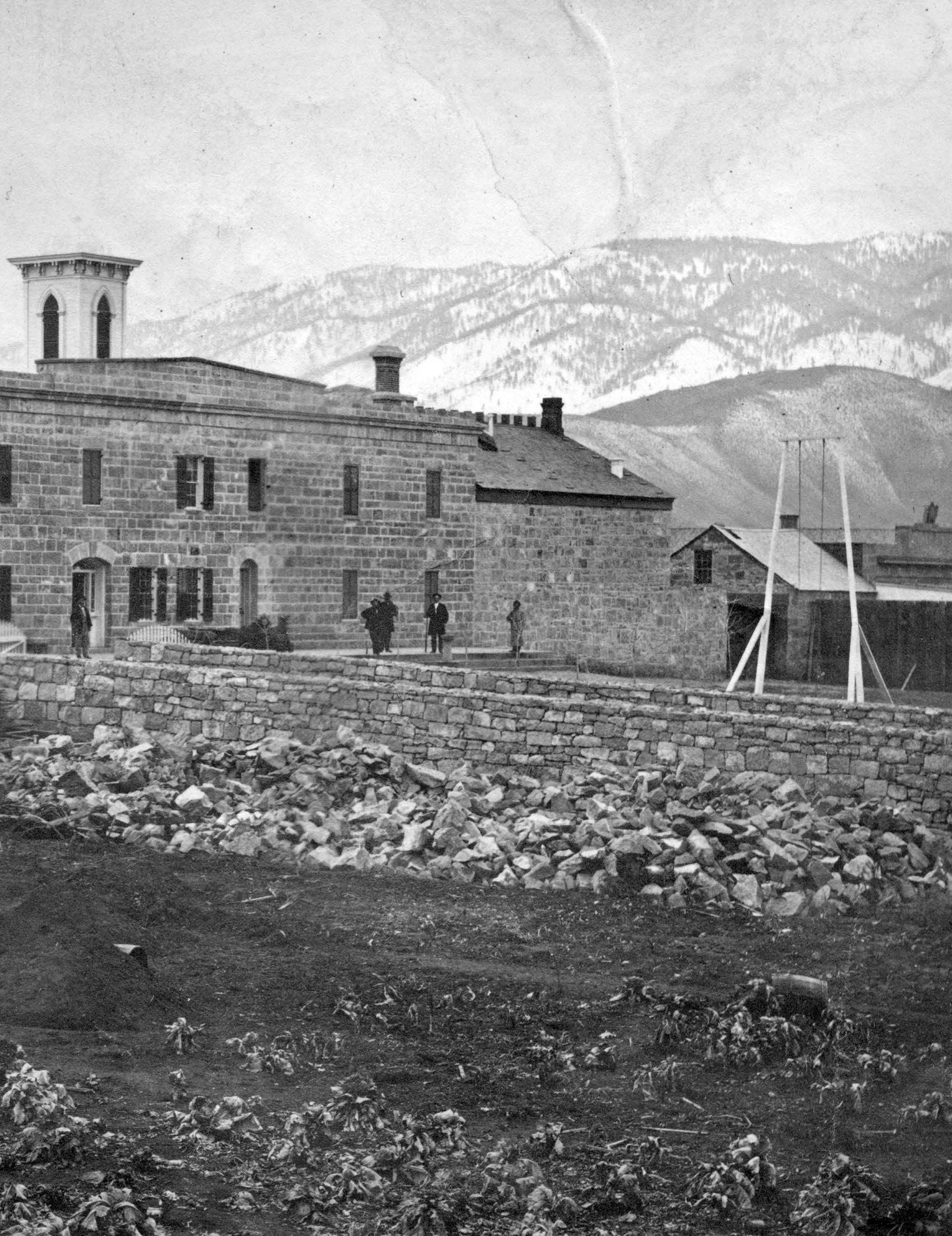

The story of the Nevada State Prison begins with Abraham Curry, the father of Carson City. Abraham Curry was one of the first settlers—and arguably the most important—of Eagle Valley, the site of Carson City. He arrived in the valley in 1858 from Utah and purchased the Eagle Ranch for $500 and several horses. On this property he built the Warms Springs Hotel using sandstone rock quarried on the site.

In December 1861, the first Nevada Territorial Legislature authorized a lease for the property adjacent to Curry’s hotel where the territorial prison would be established. Curry was appointed the first warden. The Territorial Legislature later authorized the purchase of this 20-acre parcel, including the quarry, for $80,000 in interest-bearing bonds.

After statehood in 1864, the constitution established the State Board of Prison Commissioners, composed of the governor, secretary of state, and attorney general. The lieutenant governor was to act as the ex-officio warden in order to provide him with a salary. Lieutenant Governor John Crossman thus became the first state prison warden on March 4, 1865.

From the beginning, the Nevada State Prison was a work in progress; the crude rock and wood structures burned to the ground twice—in 1867 and 1870—eventually replaced by the earliest sandstone buildings.

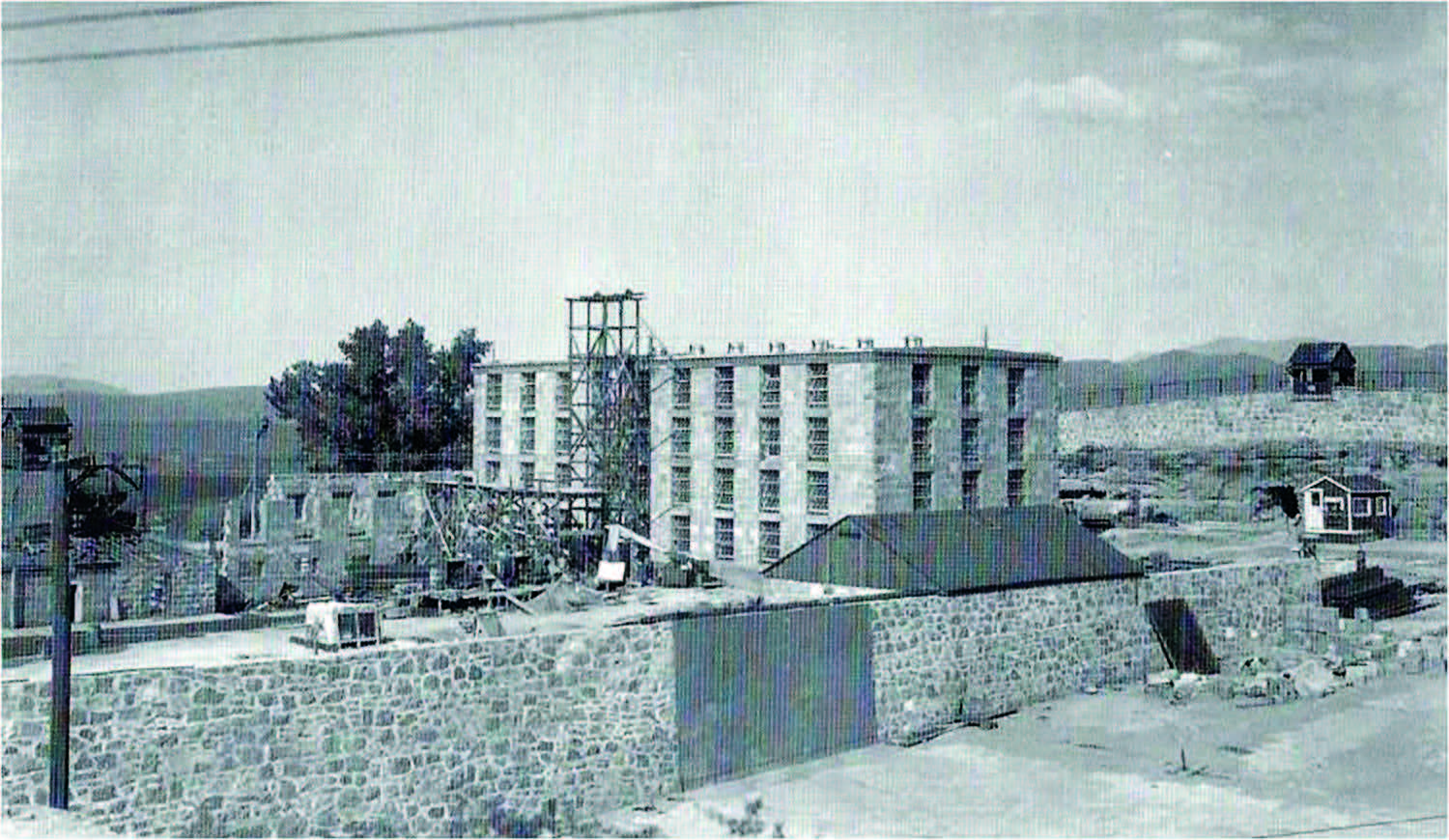

A major milestone occurred from 1924-1925 when much of what existed at the time was replaced with what we see today. The north and west wings were constructed, forming two sides of a roughly square footprint. The area of the quarry also served as the prison yard. The sheer sandstone wall that marks the west boundary of the quarry became part of the perimeter security scheme, scaled by an escapee only once in the modern history of the prison.

A major milestone occurred from 1924-1925 when much of what existed at the time was replaced with what we see today. The north and west wings were constructed, forming two sides of a roughly square footprint. The area of the quarry also served as the prison yard. The sheer sandstone wall that marks the west boundary of the quarry became part of the perimeter security scheme, scaled by an escapee only once in the modern history of the prison.

The year 1925 also brought the completion of A-Block, a four-story cell house designed by Frederic Delongchamps, with a more refined exterior than any previous structures. The B-Block was constructed in 1948, and 1961 saw the completion of C-Block; the three blocks make up the east wing of the prison. As many as 600 inmates were housed here in later years. The south wing is the modern kitchen and dining room.

A GIANT LEGACY IN SANDSTONE

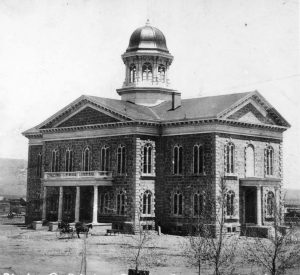

The quarry was a busy place from 1870 to 1940 as the demand for sandstone building blocks increased. Many of the buildings that used the sandstone are listed on the National Historic Register, and the city core includes the State Capitol (est. 1871), the United States Mint/Nevada State Museum (est. 1869), and the old Ormsby County Courthouse/Nevada Attorney General Office (est. 1921). Several fine old homes on the west side of Carson City feature the sandstone blocks, also.

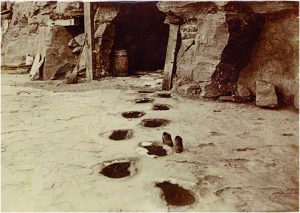

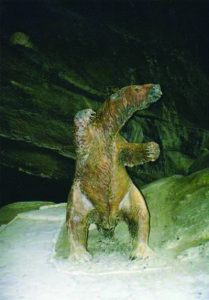

As layer after layer of sandstone was cut from the quarry, a wealth of fossils and fossilized tracks were revealed, including mammoth, bison, horse, deer, big tooth cats, and wolf. At a layer near the current floor of the quarry, an amazing discovery took place: the tracks of a species whose footprints, at first glance, appeared to be those of a giant human.

As layer after layer of sandstone was cut from the quarry, a wealth of fossils and fossilized tracks were revealed, including mammoth, bison, horse, deer, big tooth cats, and wolf. At a layer near the current floor of the quarry, an amazing discovery took place: the tracks of a species whose footprints, at first glance, appeared to be those of a giant human.

In 1882, the Carson City Sheriff communicated the discovery to the California Academy of Science in San Francisco where the footprints were correctly identified as belonging to the late Pliocene Era, but incorrectly attributed to a previously unknown race of giant humans. Estimated at 2 million years old, the footprints measured 18-21 inches in length and 8-9 inches wide. Scientists explained the lack of human foot contours by suggesting that the person might have worn sandals.

Other scientists reviewed the evidence and concluded that the fossilized prints were those of a giant sloth who lived about 1.6 million years ago. Varied interpretations concerning the origin of these mysterious footprints fueled an academic debate that persisted well into the 20th century. In the end the sloth advocates won out. The footprints were exhibited at the Columbian Exposition, Chicago World’s Fair, in 1893. The fossil field remains a rich site of historic significance for future study.

THE GREAT ESCAPE

In the late afternoon of Sept. 17, 1871, the prison’s most dramatic event occurred. The captain of the guard was attacked while locking the inmates in their cells. Twenty nine inmates participated in an escape, acquiring guns from the armory, shooting Lieutenant Governor Frank Denver and several guards, killing two people. Most were captured; a posse hanged two, and the ringleader was never found. Convict Lake in Mono County, California, is named for the location where the remaining escapees made their last stand.

THE GREAT PRISON WAR OF 1873

In 1872 the portion of the Nevada Constitution naming the lieutenant governor as the prison warden was repealed. Wardens would now be appointed by the governor, but Lieutenant Governor Frank Denver refused to hand over the prison, and refused to allow the governor, or any other members of the prison board, to enter the prison. Finally, Governor Lewis R. Bradley called out the militia in March 1873. Confronted by 60 soldiers and a small artillery piece, Denver surrendered the prison.

BIG HOUSE CASINO

Between 1932 and 1967, a Nevada-style casino operated within the walls of the prison. There is no other example in the history of penology in the U.S. where a casino operated inside a prison, and where inmates were allowed to gamble at table games. Indeed, this uniquely Nevada experience seems completely at odds with prison theory at the time.

Between 1932 and 1967, a Nevada-style casino operated within the walls of the prison. There is no other example in the history of penology in the U.S. where a casino operated inside a prison, and where inmates were allowed to gamble at table games. Indeed, this uniquely Nevada experience seems completely at odds with prison theory at the time.

References to legalized gaming in the Nevada State Prison are not exactly accurate. The prison was never issued a gaming license, or in any way recognized by Nevada gaming authorities. Rather, the casino was more or less ignored. If an application for license had been made, it surely would have been denied based on the unsavory character of the applicants. During its heyday, the prison casino included games of blackjack, craps, and poker; sports’ betting was also a popular feature. The casino was located in its own building, a large sandstone structure known as the bullpen. The inmates who ran the games kept most of their winnings. Inmates who gambled successfully were likewise allowed to keep their riches, and a percentage of the take was deposited in the inmate welfare fund, an act certainly intended to give some legitimacy to the practice.

Throughout its 35 years, various wardens tolerated the casino. This changed in 1967 when a new warden demanded that the casino be closed. A measure in the state senate to close the casino failed, but shortly afterwards, the governor and prison board used administrative authority to shutter the casino. The building which housed the casino was demolished.

THE FUTURE OF THE NEVADA STATE PRISON

This is but a small sampling of the rich collection of stories from the annals of the Nevada State Prison. The decommissioning of the prison triggered a requirement to change its official use from occupied prison to public historical site and the society is working its way through the permit process. Once complete, the public will be allowed to enter the prison for tours and lectures, and to view the exhibits. In the interim, the society is using this time to collect and catalogue artifacts, to continue researching and documenting the history of this institution, and to inform the public through the NSPPS lecture series.