The Petticoat Prospectors

November – December 2016

The Petticoat Prospectors

Looking back: The little-known history of female miners in the Silver State

Looking back: The little-known history of female miners in the Silver State

BY TERRY SPRENGER-FARLEY

“We do not see any reason why women should not engage in mining as well as men. If they can rock a cradle, they can run a car; if they can wash and scrub, they can pick and shovel.

Although some gentlemen friends of the ladies are attempting to persuade them from continuing work, they are determined and we are pleased to see it.” —Article in the Territorial Enterprise, 1871

The venerable Comstock newspaper—in a story about a group of women that not only opened but excavated a mine in Virginia City in 1871—had high praise, a rare thing. Female prospectors were scarce during the early Gold Rush years, but a few tenacious souls braved the prejudice, scorn, and back-breaking work as they searched for riches in Nevada’s desert boomtowns. Their work helped pave the way for today’s mining industry; last year the Nevada Mining Association—formed in 1912—named its first female president, Dana Bennett.

So who were these early rebels and pioneers? In our November/December 1983 issue, Nevada Magazine ran a wonderful story about some of these colorful women. Read about how they overcame obstacles and stood their ground for their right to earn a place in history.

Tales of the Comstock Lode—the camaraderie, hard work, adventure, and sudden wealth—filled the fantasies of many children in the late 1800s, and the images appealed as much to young girls as to their brothers. And more than a handful of those girls, grown up, leapt at the chance to strike it rich in Nevada’s mining boom at the turn of the century—no matter the cost.

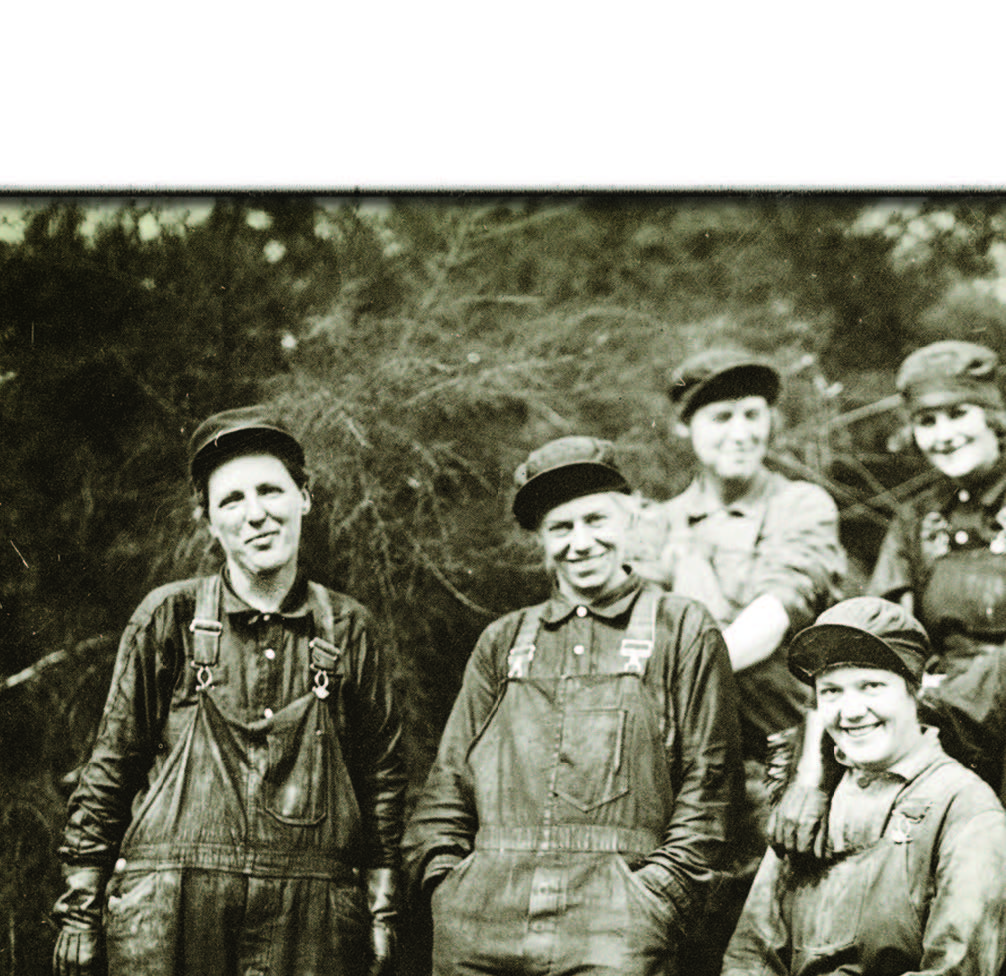

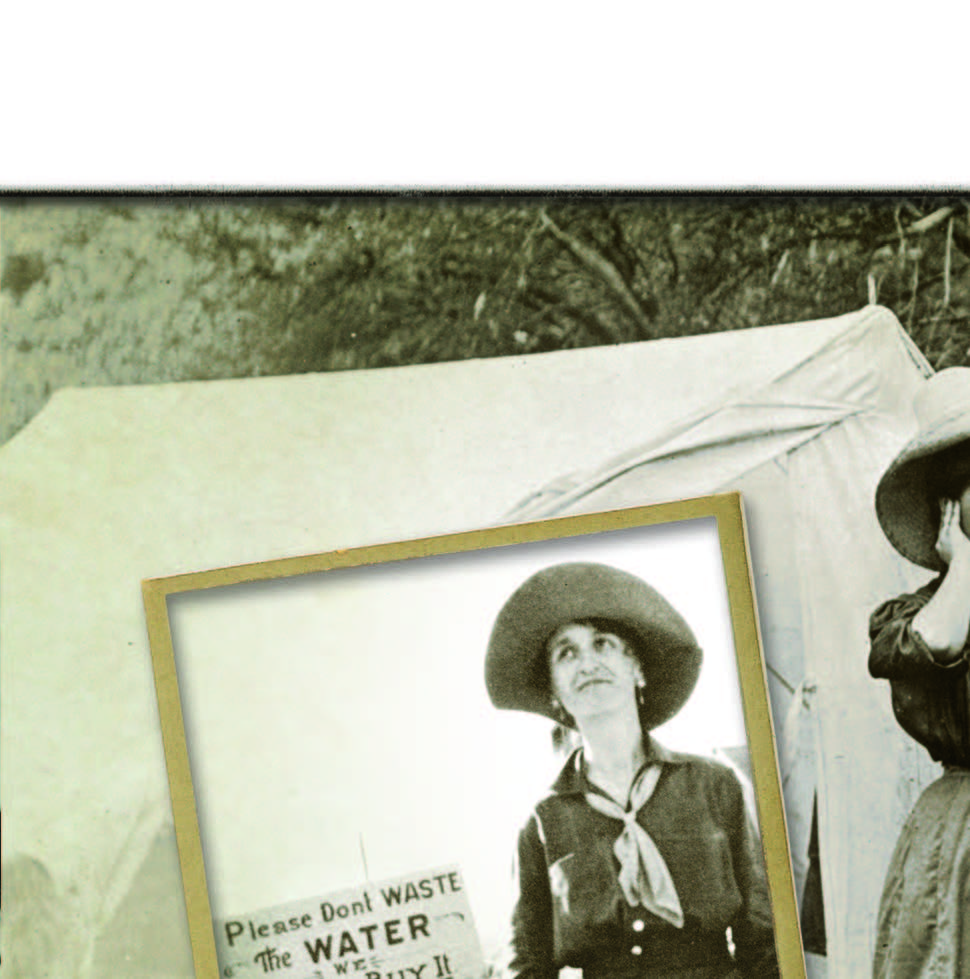

Trading tea dresses and milky complexions for trousers and skin-like mule hide was the first part of the exchange. A lady prospector also had to work harder and longer than her fellows. She paid higher wages to those who deigned to help her in spite of her sex. And she toted a pistol in her waistband to show she was no tenderfoot and could sting like a rattler if the occasion demanded.

LILLIAN MALCOM

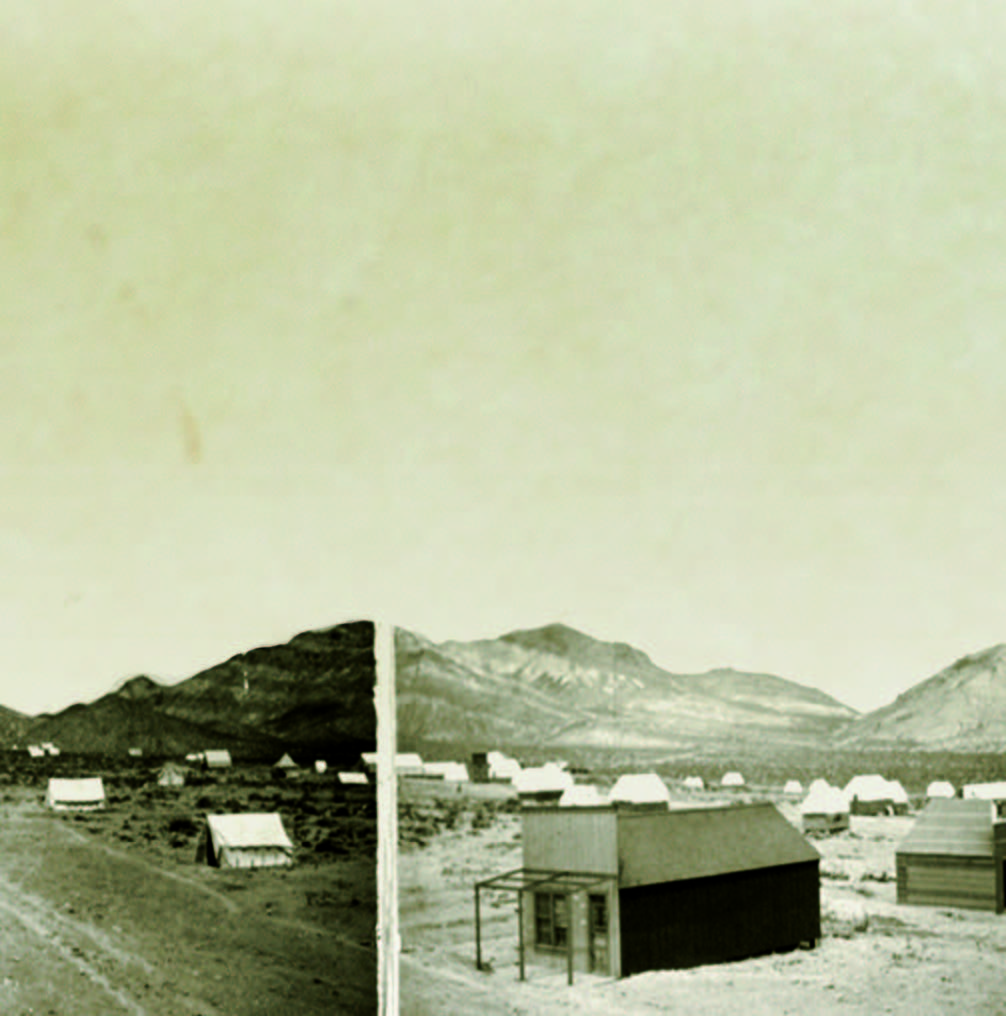

Luckily, Lillian Malcom was no tenderfoot when she arrived in the Bullfrog mining district in 1905. Bullfrog was at its most primitive stage. Miners’ homes were dugouts or tents, huts made of mud and manure blocks, or flour barrel frames covered with rough feed sacking. Prospectors in this rude town were eager for diversion. When Lillian, pretty and fresh from the Klondike, told her stories in boarding houses (which were usually tents) for the price of a beefsteak (which cost as much as a man could mine in a month), even the most skeptical allowed that this little lady might make it.

Luckily, Lillian Malcom was no tenderfoot when she arrived in the Bullfrog mining district in 1905. Bullfrog was at its most primitive stage. Miners’ homes were dugouts or tents, huts made of mud and manure blocks, or flour barrel frames covered with rough feed sacking. Prospectors in this rude town were eager for diversion. When Lillian, pretty and fresh from the Klondike, told her stories in boarding houses (which were usually tents) for the price of a beefsteak (which cost as much as a man could mine in a month), even the most skeptical allowed that this little lady might make it.

Lillian had lived in a world of snow, dog sleds, and gold for several years. But the adventure which drove her to Nevada had been a spring snowshoe trek of 175 miles from Kugarrock to Nome in Alaska.

“The ice was treacherous and the snow was melting,” Lillian told listeners who sat on bedrolls or in the dirt. “The rivers were breaking up and we had to jump from one cake of ice to another. Once I fell in and nearly drowned. The party ran out of grub, and if it hadn’t been for the tomakius—a sort of white pheasant—we would have starved.”

Miners weren’t the only ones enthralled by Lillian’s stories.

Her looks and lively tongue made her an instant “character,” and the newspapers loved her.

When Lillian announced that she and a couple of old timers were going to cross Death Valley looking for richer diggings, a crowd gathered in front of the Merchant Hotel to see her off, and the Tonopah Bonanza applauded her bravery in undertaking a trip “not always made without loss of like, even by strong, robust manhood.”

“She did not betray any apprehension—on the contrary, she was smiling and happy and told reporters Death Valley had no terrors for her,” the Bonanza marveled.

Then, because she was, after all, Bullfrog’s leading lady, the newspaper described Lillian’s prospecting trousseau.

“Her hair was braided and tied in numerous labor-saving knots with white baby ribbons. Her face was pretty, but certain to lose its feminine delicacy and whiteness ere the sun’s rays of Death Valley get through with it, especially as her light-colored felt hat was narrow-brimmed.”

Onlookers who appeared to be watching her four stamping horses might well have been considering her skirt length, which, the Bonanza reported, was quite a bit shorter than usual. It wasn’t indecent, though, since it “made a safe junction” with her tan boot tops.

Lillian said she had a pair of men’s khakis in her saddlebag which she would don once she “got out a ways.” Certainly it’s only speculation that this remark enticed reporter Anthony MacCauley to accompany the prospecting troupe on its perilous journey.

MRS. JENNIE ENRIGHT & MRS. GEORGE H. LEWIS

While Lillian had to search for rich grounds in California, two of her sister miners made themselves rich right in Goldfield. Mrs. Jennie Enright and Mrs. George H. Lewis were partners. They had bought their claim from another woman, Bessie Miller, who, according to the Goldfield Daily Sun, “parted with her holdings for a tidy sum.” Jennie and Mrs. George didn’t mind laying down the sum, for they were still flushed with success from a $50,000 profit they’d made on another claim.

While Lillian had to search for rich grounds in California, two of her sister miners made themselves rich right in Goldfield. Mrs. Jennie Enright and Mrs. George H. Lewis were partners. They had bought their claim from another woman, Bessie Miller, who, according to the Goldfield Daily Sun, “parted with her holdings for a tidy sum.” Jennie and Mrs. George didn’t mind laying down the sum, for they were still flushed with success from a $50,000 profit they’d made on another claim.

Their final transaction did involve a perilous journey, but it was more frightening for a San Francisco investor than for the veterans of Goldfield’s petticoat brigade. L.R. Keough had come to see to this company’s interests. When he left with the two ladies on a Saturday afternoon in August, intending to visit claims a few miles from town, he expected a pleasant outing. But the day grew dark and torrential rains destroyed their trail markers on the lakebed. It wasn’t until 10 o’clock that night that Jennie, driving the skittish horses, spotted a landmark.

They gathered ore samples and headed the team back toward Goldfield, where they arrived at 2 a.m. soaked and chilled.

“Mr. Keough was considerably impressed with the courage of the women of the mining camps,” the Sun bragged, “as well as their ability as horsewomen.”

Keough was impressed enough that he set the women up with enough money to pursue their wildest prospecting dreams. The new Goldfield Gold Lake Mining Company brought Jennie and Mrs. George $5,000 in cash and 4,500 stock shares.

HELEN COTTRELL

A dead man’s map led Helen Cottrell to her fortune. She originally had to come to the Manhattan area to prospect, but things went sour, so Helen turned to the relatively safe and lucrative task of selling supplies to the miners she envied. But her dreams resurfaced when an exhausted prospector told her he was giving up.

His brother had mined in the wilds of the Toiyabe Range before suddenly leaving for Mexico, where he had been killed by Yaqui Indians. Before his death he had drawn a detailed map of his claim and mailed it home. But, the prospector sighed, it hadn’t led to any silver or even to the cabin his brother had described. He laughed at Helen’s excitement and told her she was welcome to the useless scrap.

Helen’s elation was contagious. She recruited two partners, and after a long search they found an old stone cabin and a forge with silver bits on it. The ore-rich ledge was harder to find, and the men with her almost gave up. Helen never did, although, she told reporters later, the place was so diffi cult to reach “a few more trips would have bankrupted me for clothing destroyed.”

Helen’s New Era Mine proved to contain gold and lead as well as silver. Unlike many Manhattan miners, she didn’t sell out to San Francisco speculators who had invested heavily in the area, and that was just as well. Her discovery took place about the same time as the San Francisco earthquake of 1906. Bay Area investors pulled their money from Manhattan and put it into rebuilding San Francisco, leaving Manhattan’s mines in the doldrums.

Helen’s independent streak, typical of the petticoat prospectors, led her to even greater wealth on the Comstock. Not content to sit on her porch and watch ore cars roll to the smelter, Helen supervised some work she had commissioned in Gold Hill. She supervised very closely, and in 1907, clinging to the side of a 20-foot shaft, she recognized the little black threads of tellurium her workers had missed and withdrew an immediate $1,600 in gold.

Few women miners were as lucky at nabbing partners as Helen Cottrell. Their sex and independence were an unappealing combination to male adventurers of the time, so some women resorted to subterfuge to get desperately needed assistance.

The Reno Evening Gazette in the 1908 reported one such attempt by an unnamed “hardworking woman” who had given up her attempts at recruiting local men. She skirted the issue of gender by hiring two miners through the mail.

Upon facing his lady boss, the experienced miner quit. But the other man smiled at the irony of his surprise. During their correspondence, he’d alluded to ore field experience he didn’t have. He was a rank tenderfoot, as entranced with the lure of the rush as his employer. The two stuck together and surprised everyone by stumbling on a claim of gold-infused rock worth $4,000 per ton.

HAPPY DAYS DIMINY

Happy Days Diminy was one of the hardest-working, longest-lived of the pioneering women. “No delicate, publicity-seeking effeminate imitation, but the genuine article,” the Goldfield Daily Tribune called her. She was led to her first strike by a ghost.

Although her “sunny disposition, unchanged good nature, and smiling optimism” earned her the nickname Happy Days, she preferred to work alone. She had been doing so for five years when, in the summer of 1912, some folks said the solitude had scrambled her brain.

A dead woman friend appeared to Happy Days, flitting about her land, snatching gold nuggets. Then a dream man materialized, explaining that the nuggets could be found there—he pointed—a mere 1,000 feet from her cabin.

He was right. After many years of working the ground and hauling timber with only two burros for partners, Happy Days came to Goldfield with a bottle in her handbag. The bottle held a small collection of gold nuggets.

The sparseness of the discovery didn’t seem to faze her. Like many of her female associates, Happy Days seemed to love the dream of wealth and the prospecting life as much as the gold itself.

The Goldfield that Happy Days knew was a town of contrasts.

Inside the raucous saloons and dancehalls, New York speculators in fine suits shared bar space with grizzled miners in sweat-stained khakis. Outside, the streets were jammed with businessmen from Chicago in their new Stanley cars, veering to miss braying, knee-locked burros. Goldfield had all the romantic excitement of the storied Comstock, and Happy Days swore she wouldn’t miss it for the world. So, when she couldn’t get San Francisco backing for her operations or even help from her husband, who had returned briefly from his own pursuits in Alaska, she pressed on alone.

She found a platinum deposit and bought herself a fruit ranch in California, and, for the first time, hired a young male helper to take a shovel to the 80-foot shaft she’d planned.

The young man, known as Smith, did his work well by all accounts. And if some folks made snide guesses about his true service to Happy Days, their speculation came to an end seven months into his employment.

“Woman Fighter Sends Man to Hospital,” the Tonopah Bonanza blared. “Happy Days Called ‘Some Scrapper.’ ” The newspaper reported Sheriff Ingalls had heard that Happy Days and Smith were engaged in a “rough and tumble scrap,” which needed a lawman’s intervention. But before he arrived, a man named Collitt had stepped in and helped the damsel in distress to “put the finishing touches” on Smith. Severe cuts, abrasions, and a broken arm sent Smith to the hospital, but Happy Days, whose injuries were comparable, balked at such treatment. As soon as she was placed on bond, she went home.

Physical injuries were just part of the territory. Unless they entailed copious amounts of blood, female miners were inclined to shrug them off.

A year before the fight, Happy Days had received a concussion when her two burros, unused to harness, upset her wagon and ran over her. After dusting herself off, she was undoubtedly made an honorary member of Goldfield’s “Tip-Over Club,” which required being thrown from a car—a common occurrence in the early 1900s.

One of Happy Days’ contemporaries, Maggie Johnson, fell down a 30-foot mine shaft and refused to leave her Goldfield cabin. She was finally hospitalized over her protests because of crippling rheumatism. Elderly and ill, Maggie had been unable to work her claim for years but had lived on its earlier bounty, refusing to lease or sell her mine.

Happy Days was luckier. The Ely Daily Times reported that she was still going strong in 1942 at age 91. She was, in fact, demanding a divorce from her third husband, 70-year old H. Jester. Perhaps the marriage just couldn’t stand the strain of Happy Days’ spirit. Still seeking support for her mining efforts, she had ridden freight trains to New York to snare Wall Street backing. Her efforts had been futile, but she was undaunted.

Happy Days ended her life as many of her sister miners had prayed to end their own. She continued to live in the stone cabin she’d built by hand, continued to cultivate a garden each spring. And, hale and hardy in her jeans and jacket, she kept her prospector’s dream alive long after it was a memory for the rest of Nevada, treading the path to Ely from her Tule Canyon claim, with a little bottle in her handbag, filled with flakes of gold.