Great Basin National Park

November – December 2016

THROUGH THE LENS: Great Basin National Park

STORY AND PHOTOS BY KIPPY S. SPILKER

STORY AND PHOTOS BY KIPPY S. SPILKER

I leave Ely at 3:15 a.m. and head to the park in hopes of catching a good sunrise. I am not disappointed.

Without traffic and construction, I make it there quicker than anticipated, and am able to photograph Wheeler Peak and the valley below under starry skies and, as the sun rises, freshly painted with alpenglow.

Land of 10 thousand rabbits. If I were to give the area surrounding Great Basin National Park a colloquial name, that would be it. And to be fair, it would likely be an understatement. Driving the western edge of the park, the views are breathtaking: beautiful, towering mountains; large rambling ranches—active and abandoned—nestled in the vast Spring Valley; and thousands of rabbits. I drive no faster than 10 mph along Shoshone Road, for fear I won’t be able to avoid them. Traffic is sparse, but every driver I pass gives a friendly country wave. For a small-town girl like me, it’s paradise.

I’m at the park in eastern Nevada for the First Light celebration of the Great Basin Observatory, which falls during the National Park System’s 100th birthday. After some cursory exploration, I head to Ely soon after sunset but take a minor diversion to the Ward Charcoal Ovens State Historic Park, having only ever seen it in pictures. With just a headlamp to light my way, I don’t explore the park much—just long enough to get a starry-night photo.

GOING UNDERGROUND

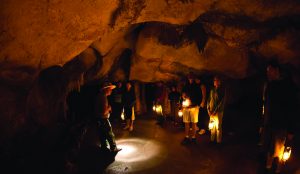

The next morning, Sales Manager Adele Hoppe and I take the 90-minute tour of Lehman Caves, located inside Great Basin National Park. Because of the centennial, the tour is conducted—for the first time ever—by lantern rather than flashlight. The cave’s beginning can be traced back about 550 million years ago, so it’s not difficult to imagine you’ve stepped back in time when making your way through the caverns and chambers of the incredible limestone-and-marble cave. Boasting stalactites, stalagmites, helictites, flowstone, popcorn, and soda straws, there’s no end to the breathtaking views. During the tour we see rare shield formations, created by two roughly circular plates fastened together. Sometimes the shields have stalactites and what are called draperies hanging from the lower plate, as seen in the cave’s famous Parachute Shields.

Our guide shows us areas where 19th century visitors broke off stalactites as souvenirs. At the bottom of some, we see about an inch of new growth, so it’s hypothesized that some sections grow an inch in about 100 years.

Elinor Tilford Charleston—who shares her centennial year with the national parks—is presented with a plaque, sash, an official park ranger hat, and the honorary assignment of Senior Park Ranger.

REACHING FOR THE STARS

The park’s remote location—along with a base elevation of 6,800 feet—plus its clear skies make it the perfect location for stargazing and astrophotography. And, it turns out, also the perfect location for the very first research-grade observatory to be placed within a national park in the U.S.

Hundreds show up for the First Light ceremony and the unveiling of the Great Basin Observatory, which will allow students and scientists to conduct research, and share images from the telescope online.

During the ceremony, Elinor Tilford Charleston—who shares her centennial year with the national parks—is presented with a plaque, sash, an official park ranger hat, and the honorary assignment of Senior Park Ranger.

A MORNING OF EXPLORATION

The next morning, I leave Ely at 3:15 a.m. and head to the park in hopes of catching a good sunrise. I am not disappointed. Without traffic and construction, I make it there quicker than anticipated, and am able to photograph Wheeler Peak and the valley below under starry skies and, as the sun rises, freshly painted with alpenglow.

The next morning, I leave Ely at 3:15 a.m. and head to the park in hopes of catching a good sunrise. I am not disappointed. Without traffic and construction, I make it there quicker than anticipated, and am able to photograph Wheeler Peak and the valley below under starry skies and, as the sun rises, freshly painted with alpenglow.

I only have a couple hours to explore, so I take a brief walk up the road toward the trailheads, and find my way to the Gray Cliffs camping area, where I am instantly smitten. I talk to the only two people camping there, and they are loving this “hidden gem.” I come across lots of animals during my travels, including deer, wild turkeys, marmots, and—you guessed it—jackrabbits.

Before the long drive home, I explore an area that appears to have some caves, and find a petroglyph, pictograph, and, less than 30 feet away, a beautiful shaded river area that looks perfect for a picnic and a break from the hot mid-day sun.

I’LL BE BACK

Governor Brian Sandoval, during his keynote address at the First Light ceremony, mentions that when he camped in Great Basin National Park with his family, he felt like they had their own private park. He and many others make comments throughout the day about the remote nature of the park and how you don’t just happen upon it—you have to really want to get there.

After spending just a short time in the park, I have to say whether you are a hiker, astronomer, photographer, fisherman, skier, snowshoer, camper, backpacker, or general lover of nature, you really should want to get there!